Nearly two years ago, the University of Virginia founded a public benefit company – “public benefit” being a key objective – to provide an affordable way for families in infrastructure-challenged countries to purify drinking water. Today that company, MadiDrop PBC – which uses an elegantly simple technology developed at UVA – has shipped more than 20,000 ceramic purification tablets to humanitarian organizations in several countries, primarily in Africa and Latin America.

MadiDrop’s production facility, administrative offices and shipping facility are in Charlottesville, though “madi” – the South African word for “water” – is universal in meaning and importance. And purifying water for thousands of people around the world who otherwise would not have regular access to clean drinking water is the company’s goal. Most of the profits from sales are reinvested to allow increased production.

UVA Today recently spoke with UVA civil and environmental engineering professor Jim Smith, who invented the technology in his lab at the University, and to David Dusseau, the company’s CEO and co-founder, to get an update on the company.

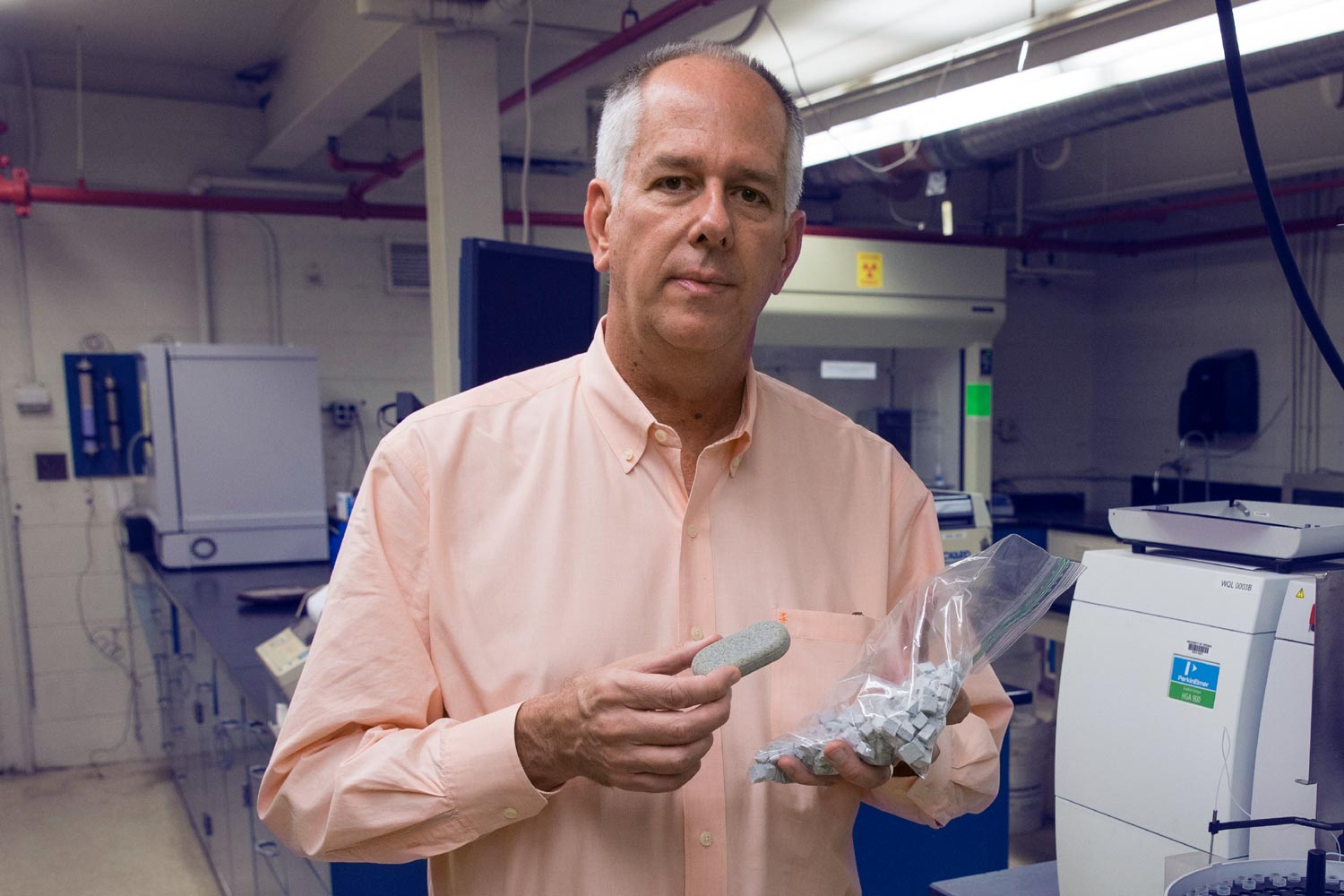

Professor Jim Smith developed the MadiDrop tablet in his UVA engineering lab. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Q. Please tell us briefly what a MadiDrop is, and how it works.

Smith: The MadiDrop is a silver-ceramic tablet that releases silver ions into water at a controlled rate. Silver ions are an excellent disinfectant for waterborne pathogens. You place a MadiDrop in a 20-liter water storage container, fill the container up in the evening, and the next morning, the water is safe to drink.

You can just keep filling the container every night for at least six months and the MadiDrop works the same way, day after day.

Q. So far, you’ve shipped about 20,000 MadiDrop tablets. How many families can that support, and for how long?

Dusseau: In general, one MadiDrop serves a family’s drinking water needs for six months, so you could say 20,000 families. However, our business has been with a variety of commercial- and humanitarian-based organizations with slightly different focuses. In addition to MadiDrops being used for immediate needs, there’s a portion being stockpiled for disaster response situations.

A better way of stating the positive impact of 20,000 MadiDrops is that this represents the potential of at least 40 million liters of safe drinking water for people across the globe.

Q. How did you get the idea to develop MadiDrop, and then get it ready as a marketable low-cost solution to a serious global problem?

Smith: I began working in South Africa with silver-ceramic water filters. They are a great technology, but they are relatively large, heavy, difficult to manufacture, and they have a relatively high capital cost – typically $20 to $40 per filter. They work well for local production and local distribution.

I could see that for many of the poorest South Africans, the filters were just not affordable. I wanted to come up with something that was small, durable, easy to manufacture, and of course, much less expensive. And of course, that is the MadiDrop. The cost for each tablet, when distributed through a humanitarian organization, averages just $5.

Q. What is your five-year plan for the company?

David Dusseau is CEO for MadiDrop PBC (contributed photo)

Q. Are you working on any additional new humanitarian technologies that might someday reach the market through MadiDrop PBC or other companies?

Smith: We are working on a couple of things involving silver. First, we are finding that silver from the MadiDrop kills mosquito larvae that potentially grow in stored household water. So the MadiDrop may be able to help reduce mosquito-transmitted diseases such as malaria, dengue fever and zika.

Also, Courtney Hill, one of my doctoral students, is developing an entirely new method to introduce silver ions into water for disinfection that is directly incorporated into a water storage container. Courtney is also working on a human health study of the MadiDrop in South Africa that involves 400 families.

Q. How many people does the company employ in Charlottesville, as well as in other countries?

Dusseau: Our main office and manufacturing is done right here in Charlottesville. We’re a small team locally and currently employ five people, in addition to utilizing international consultants and contractors in regions where we need specialized knowledge.

Q. Please tell us how the experience of delivering good water quality to people in need has affected you personally.

Smith: I am seeing the data come back from our human health study of the MadiDrop in South Africa and it is dramatically improving the safety of the household water. It is having a huge impact on the health of the local residents, particularly the children. That is really satisfying!

Dusseau: Every week, we’re receiving feedback from people scattered across 40 countries – be it the end user, or an organization that started a MadiDrop program. The overwhelming message is that people like using the MadiDrop for their safe water needs, and most importantly, their health is improving. It is this significance that keeps my team and I motivated to navigate the daily challenges of a start-up business – and not just any start-up selling the next digital widget – a company tasked with introducing a brand new type of technology to global commercial and humanitarian channels.

Overwhelming at times, yes, but well worth the effort.

Media Contact

Article Information

July 20, 2017

/content/40-million-liters-dirty-water-now-safe-drink-thanks-uva-enterprise