The University of Virginia’s Department of Environmental Sciences has conducted research on Virginia’s barrier islands, mainland and seaside bays of the Eastern Shore since 1986 with funding from the National Science Foundation’s Long Term Ecological Research project. For several years, researchers operated out of a farmhouse jury-rigged as a field lab. But with major funding from the Anheuser-Busch Companies and donor Paul Tudor Jones, and with National Science Foundation grants, the University established its Anheuser-Busch Coastal Research Center in 2006.

The state-of-the-art facility is located on 42 acres in the town of Oyster, about 15 miles north of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. It includes lab space, a residence building that can accommodate 30 people, and a dock for its fleet of five shallow-water research vessels. Much of the research is conducted on the Nature Conservancy’s Virginia Coast Reserve.

The center’s site manager, Art Schwarzschild, holds a Ph.D. in environmental sciences from U.Va. He spoke recently with UVA Today science writer Fariss Samarrai during a busy three-day seagrass survey.

Q. Tell us about the research conducted by UVA investigators at the facility.

A. Scientists working with the Virginia Coast Reserve Long-Term Ecological Research program are studying the coastal environments of the Eastern Shore, from the upland portions of the peninsula out to the ocean side of the barrier islands. On any given day our researchers conduct field work on seagrass meadows, forested streams, abandoned farm fields impacted by saltwater intrusion, salt marshes, oyster reefs and on the barrier islands. These investigators – atmospheric scientists, chemists, ecologists and geologists – study everything from the atmosphere above our heads to the groundwater under our feet.

We are seeking a better understanding of the complex dynamics of the coastal barrier island systems and how different ecosystems are linked by major environmental forces like climate change, rising sea level and human land use.

Using an array of stationary and transportable environmental monitoring equipment, our faculty and graduate students are gaining insights to the way coastal storms and sea level rise shape barrier islands and salt marshes and affect a range of plant and animal species. We also are studying the effects of non-native plant species on native populations, and the way native species like the Virginia oyster create habitat for other species.

Our biggest questions revolve around the idea that ecosystems may have multiple stable states that can change as the result of traumatic events, such as storms, or steady environmental pressures, such as sea-level rise and the gradual intrusion of salt water into ground water.

Q. Some of these studies have been going on for a few decades. What is gained by doing long-term research on natural systems?

A. Climate change and sea-level rise take place over long time scales, and the impacts they have on long-lived species, the cycling of nutrients, or the local geology may take years to see and understand. As a result, we are running long-term experiments designed to match the time scale of environmental changes. This gives us a big-picture view from the snapshots we keep taking.

Q. How does this relate to human activities – our effects on natural systems, and the feedback effects on our own lives?

A. Humans are part of the ecosystems in which we live. Our decisions and actions directly affect the ecology. Our program examines how the environment impacts human populations and the local economy.

So, for example, bringing back the seagrass meadows, which we’re working on, and improving water quality can help the populations of striped bass, speckled sea trout, blue crabs and other species of commercial interest. Improving and maintaining water quality is also important to the growing aquaculture industry on the Eastern Shore, which is providing fresh clams and oysters to Virginia and beyond.

Q. What does your job entail as site manager?

A. My job is as varied as the research conducted here. I help plan field projects, drive the boats, maintain field-monitoring equipment and run routine environmental sampling. Along with my staff, we make sure dorm and lab space and boats are available for visiting scientists, and keep the boats and trucks in good working order.

One of the most enjoyable parts of my job is running our outreach and education programs. I co-teach a [January Term] nature-writing class and also teach an introductory marine biology class. We run a series of professional development workshops for schoolteachers and host field trips for local elementary, middle and high school classes. And each year we hire undergraduate students and local high school students as summer science interns.

Q. How satisfying is this work for you?

A. Simply put, I love my job! The other day I took a visiting group out to some of our study sites and they commented on what an amazing experience it was to get out in a boat on our coastal bays. My response was, “Can you believe I get paid to do this?”

The fun thing about running a field station is that new people are always coming out to do new and interesting research projects. I get to be a firsthand participant in this. I also get to witness the amazement of a student catching a first crab or seeing a dolphin jump in front of the boat. Sure, there are days when the weather is not great – some long, hot days spent collecting samples in muddy salt marshes with loads of mosquitoes and biting flies – but I see this as the price for all the great days on the water and learning new things.

As an environmental scientist and someone who loves being out in nature, I cannot think of a better or more enjoyable way to make a living. I also really relish the notion that the work I am doing is helping to protect the environment, training the next generation of field scientists and helping more people to learn about the wonders of our coastal ecosystems.

Graduate student Amelie Berger and Jimmy Lord, an intern from Broadway Academy who is part of the Coastal Research Center’s Research Experience for High School students program, take a core sample from a seagrass meadow. Photos by Sanjay Suchak / University Communications

Seagrasses provide habitat for a range of other species, from sponges and fishes, to crabs and mollusks.

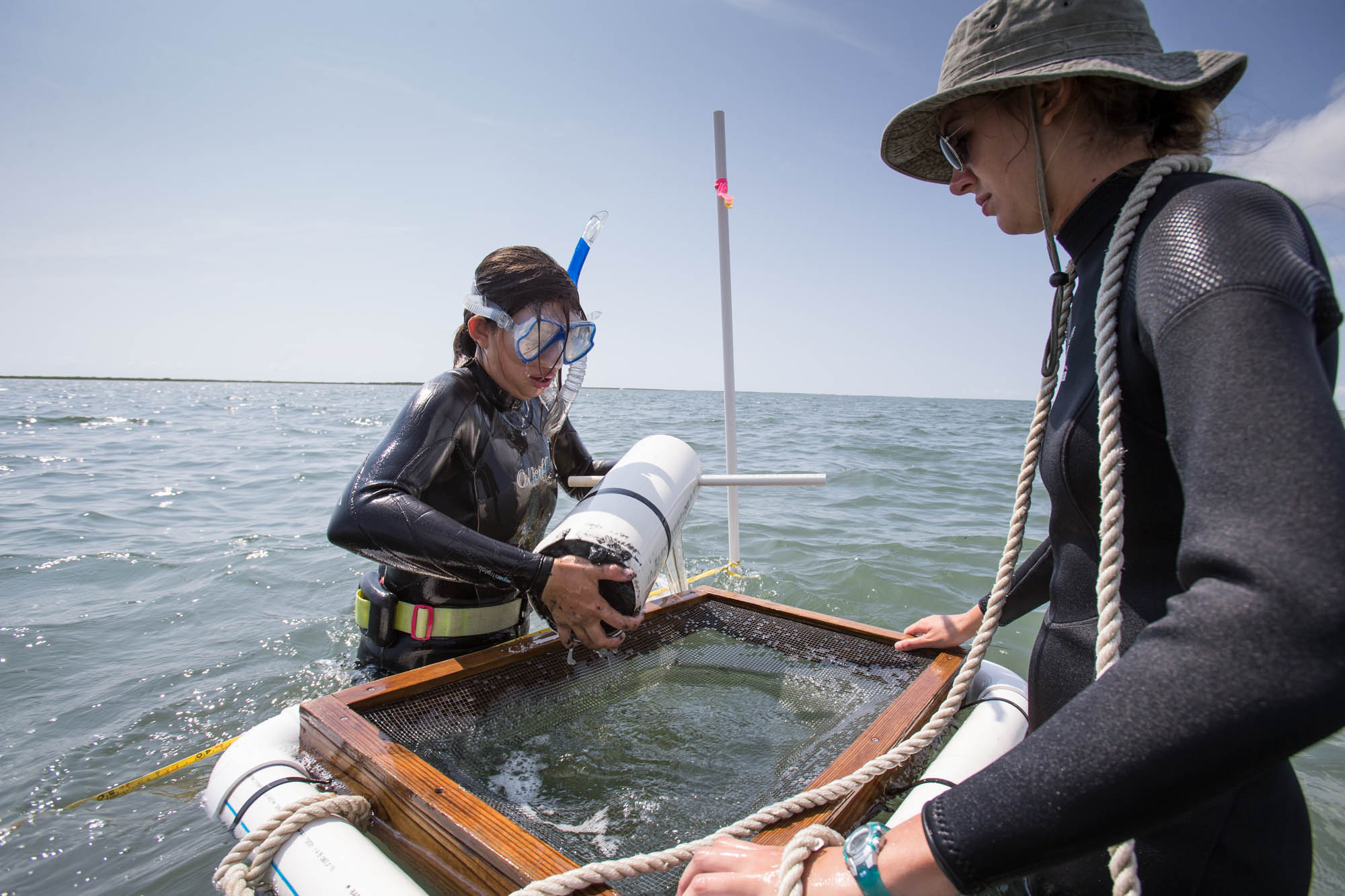

Ph.D. candidate Lillian Aoki (left) and undergrad Amy Bartenfelder prepare to sift a core sample for biomass.

Aoki and Bartenfelder sift sediment from seagrass samples.

A student sifts through seagrass samples.

Berger and Lord take a core sample from a seagrass meadow.

Researchers gather seagrass biomass from mud core samples.

Bartenfelder is one of nine undergraduate interns working as part of the Coastal Research Center’s Research Experience for Undergraduates program. Here she collects seagrass samples.

Berger displays a clam, which are abundant in the mud of restored seagrass meadows.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 7, 2015

/content/place-coast-uva-conducts-long-term-research-eastern-shore