Illustrations, political cartoons, commercial art and caricatures from turn-of-the-century London and beyond are on display as part of a new exhibition at the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

“Drawn From Life: Collecting Cartoons and Caricatures,” runs through May 24 and primarily features artwork ranging from late 19th century through World War I, though it includes some art dating from as far back as the Civil War. The exhibition is free and open to the public during business hours on the first floor of the Harrison Institute and Small Special Collections Library.

The exhibition includes about 40 items, including commercial illustrations, children’s art, examples of “Regency Nostalgia” – a popular type of late 19th-century artwork that glorified pastoral life – as well as caricatures and wartime art.

The display draws both from Special Collections and from a collection of art on loan from John Francis, a Charlottesville resident whose grandfather – Edward William Francis – acquired cartoons and illustrations between 1905 and 1922 while living in London’s Chelsea neighborhood.

The era was a boom period for commercial artwork; technological advances were making it easier for magazines, books and other publications to print images, but photography was not yet the dominant medium for illustrations, Francis said.

The result was a steady demand for quickly produced commercial art, which helped support a community of artists living in Chelsea. John Francis, who inherited the collection, isn’t sure how his grandfather came by the artwork – he passed away before his grandson was born. Though John Francis compiled biographical information on the artists for a book, which is on display with the exhibition, he wasn’t able to find much on his grandfather.

“Maybe he just knew these guys from down at the pub, or maybe he made it his business to collect autographs from artists in the area,” Francis said.

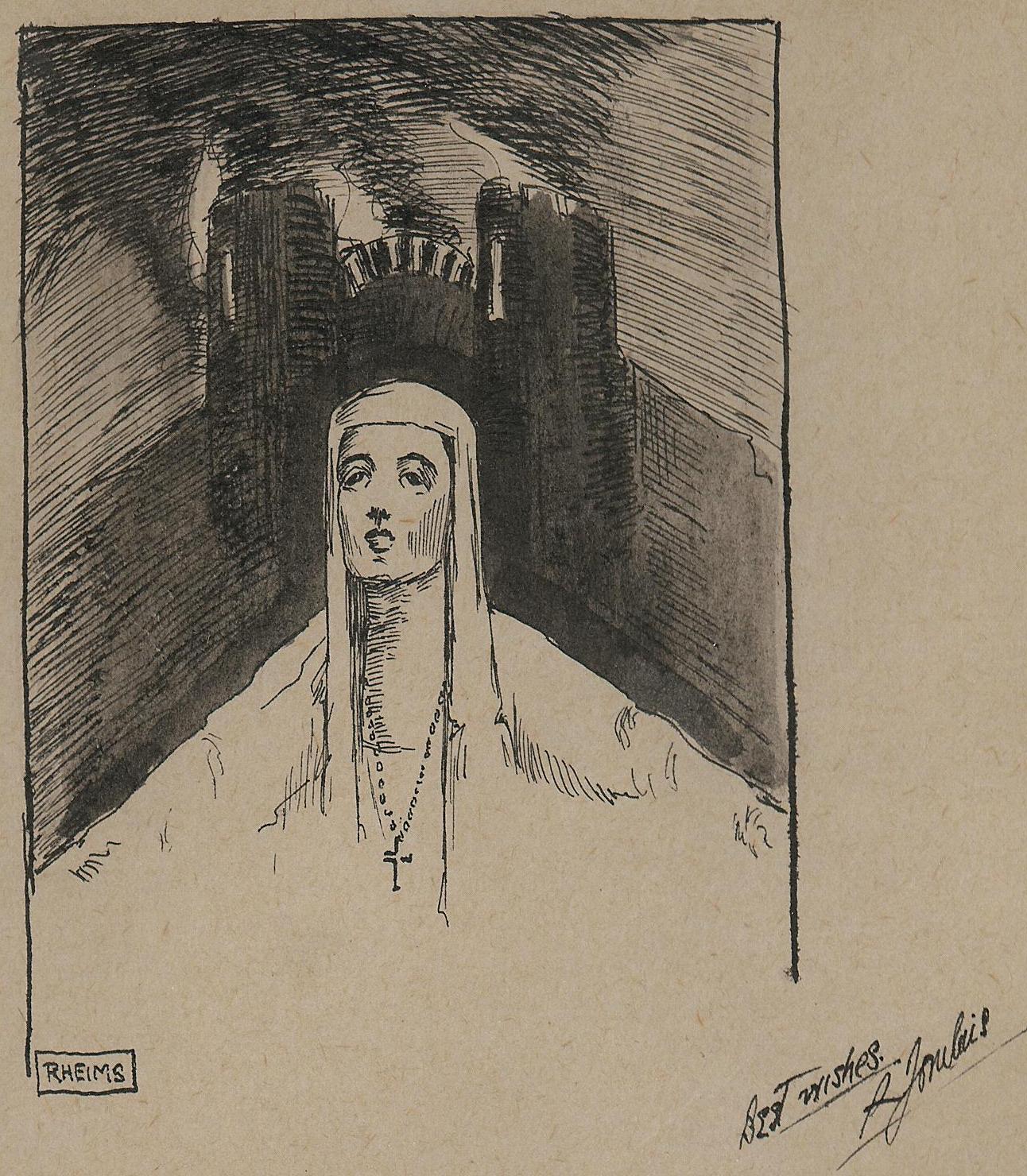

The artwork ranges from a somber black-and-white political cartoon commemorating the burning of the French city of Rheims during World War I to artist Christopher Heaps’ light-hearted sketch of what appears to be a devil. An inscription on that sketch praises Edward William Francis for his persistence, which leads John Francis to believe his grandfather wasn’t shy about asking for artwork.

At the time, it was common for collectors or admirers to ask for autographs or sketches from artists, Francis said. Many of the Special Collections items come from a collection given to U.Va. by Bernard Meeks, a collector who regularly requested work from specific cartoonists and also collected earlier cartoons. “Because of him, we have some marvelous examples of really significant cartoonists,” said Special Collections Curator Molly Schwartzburg.

Pairing the Francis collection with materials from Special Collections was a good fit, because U.Va. has many vivid examples of commercial art, cartoons and caricatures from the U.S., which allows the exhibition to give an overview of what was happening during the era on both sides of the Atlantic, Schwartzburg said.

One of the items in the exhibition drawn from the Meeks collection is an original piece by Thomas Nast, one of the most famous political cartoonists in American history. It’s a Civil War-era cartoon of Gen. William Sherman called “The Accommodating Jumping Jack,” which shows Sherman divided in two. In the half labeled “Virginia,” he is smiling and – oddly – wearing his long johns over his clothing; in the half labeled “Ohio,” he is shown with a bared sword, ready for attack.

Because the cartoon is undated, it’s hard to know what particular event it refers to, Schwartzburg said. Displaying such undated art affords curators a chance to draw on the expertise of historians or others who might be able to fill in the gaps, she said.Because the cartoon is undated, it’s hard to decipher its exact meaning, which was likely in response to a specific event or time, Schwartzburg said. Displaying such undated art affords curators a chance to draw on the expertise of art historians or others who might be able to fill in the gaps, she said.

Other items on display show the power of visual media in reflecting and manipulating public opinion about World War I. One set of illustrated children’s blocks – possibly the kind of work a commercial artist from Chelsea would have been contracted to create – has a different block for each letter of the alphabet. The letter “T” is for “Trench,” and shows a picture of a wartime trench. The letter “H” is for “Howitzer,” and has a picture of the artillery piece.

Yet other art in the exhibition seems to chronicle the war’s destruction. The drawing of Rheims features a nun in the foreground with a burning cathedral behind her.

“There was a lot of commercial artwork of this type of during the war, which differs significantly from propaganda,” Schwartzburg said. “This work is as much a statement of mourning as it is political commentary, and could be interpreted both as an anti-war statement and pro-war propaganda.”Read more about the exhibit and see examples of the artwork on the Special Collections blog, Notes from Under Grounds.

Media Contact

Article Information

February 11, 2013

/content/special-collections-exhibit-showcases-illustrations-era-photos-were-widepsread