In 1861, Alexander H. Stephens, vice president of the short-lived Confederate States of America, gave a speech about the Confederate constitution, which included justifying and codifying the continuation of slavery as the basis for secession.

The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. … [I]ts foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man.

Today, more than 150 years later, only 8 percent of high school seniors identify slavery as the central cause of the American Civil War, according to a 2017 study from the Southern Poverty Law Center.

That finding, along with inquiries from teachers themselves, helps build the case for providing teachers of kindergarten through grade 12 with content and resources they can use to include the history of slavery and racism in the United States in their classroom instruction.

In Charlottesville, the violent protests of white supremacists on Grounds and in town last summer made equipping teachers with those resources even more urgent, said University of Virginia English professor Victor Luftig, who directs UVA’s Center for the Liberal Arts. The center offers free workshops to the commonwealth’s primary and secondary teachers, presenting new and enriching content for their professional development and for use in a range of classrooms.

When he sent the word out in the fall about the daylong Saturday workshop, “Resources for Teaching the History of Race in the United States,” the response was bigger than for any other program, he said. Usually 30 to 40 teachers from Virginia will show up for a particular topic, but this time nearly 200 expressed interest. Ultimately, 100 teachers from more than 40 school divisions attended the March 17 program in UVA’s Zehmer Hall, where the center is located. Several teachers even made the trip from Washington, D.C., Maryland and North Carolina.

The center’s program coordinator, Becky Yancey; associate director Natsuko Rohde; and the Zehmer Hall staff flawlessly managed the sudden surge, Luftig said, adding, “This might be the most productive event the Center for the Liberal Arts has run in my 18 years of directing the center,” he said.

Luftig reached out to two partners the center has worked with before: UVA’s Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies and the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Teaching Tolerance project, to see what resources they might present to the teachers.

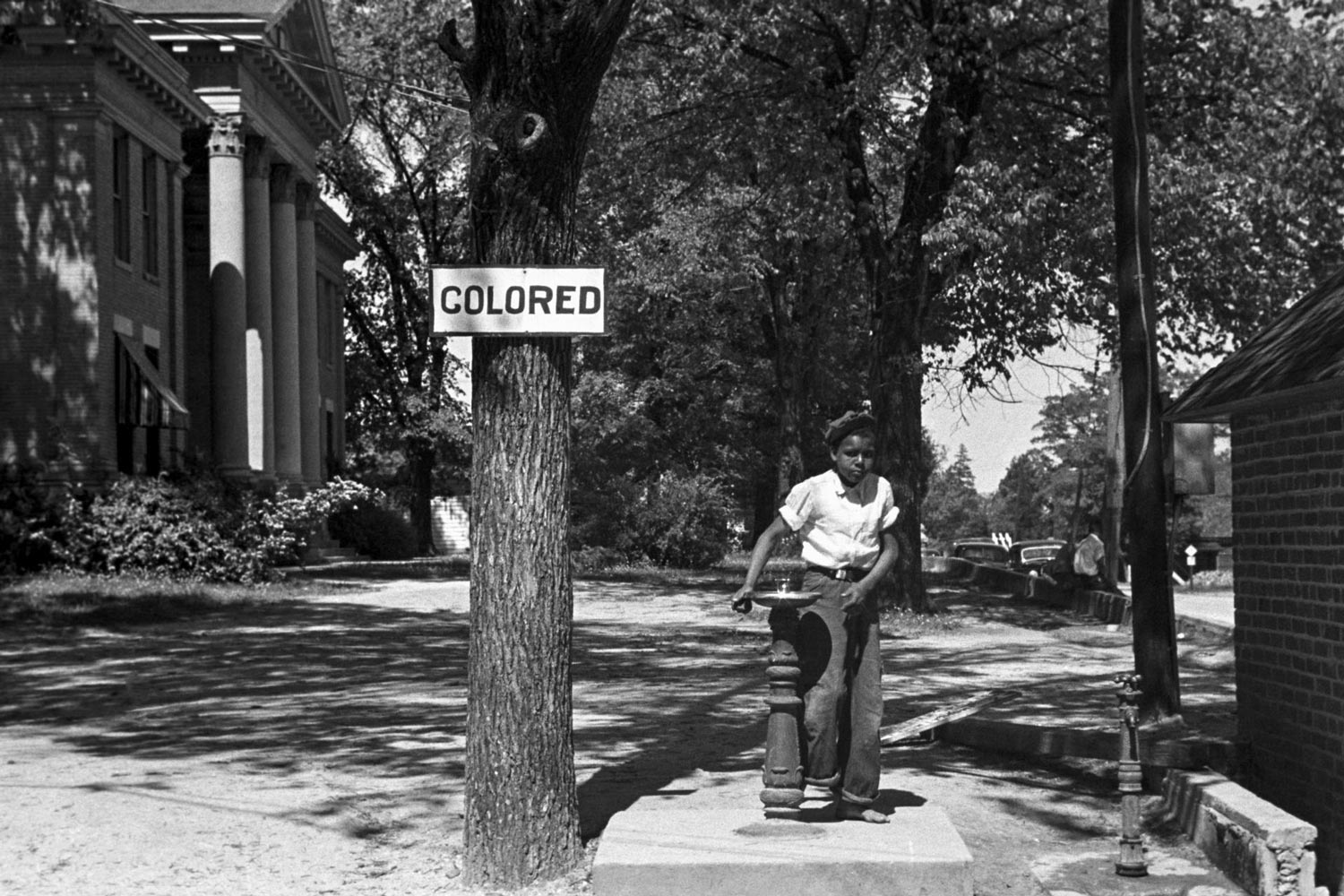

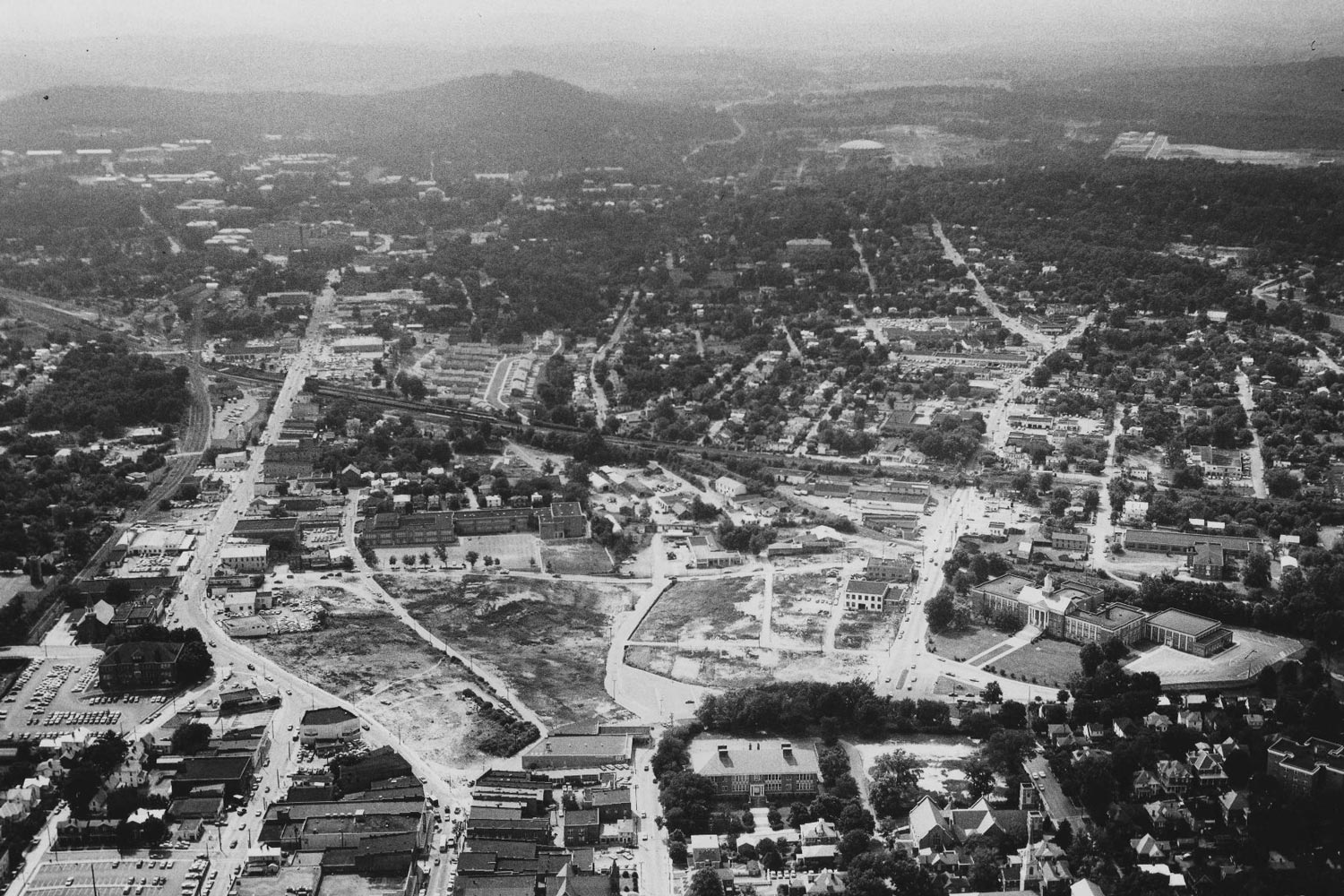

The free program introduced teachers to the Teaching Tolerance project’s “Framework for Teaching American Slavery,” an education guide that includes primary-source texts and images, teaching models, podcasts, a list of key concepts and summary of objectives; as well as the Woodson Institute’s website, “The Illusion of Progress: Charlottesville’s Roots in White Supremacy,” which explores this history and broadens the focus beyond Charlottesville’s Confederate statues. The Web-based project aims to show how entrenched stereotypes of racial difference enabled socioeconomic injustices to take root, thwarting black people’s claims to personhood, citizenship and basic freedoms.

Victor Luftig has directed UVA’s Center for the Liberal Arts since 2000. Patrice Grimes of the Curry School of Education attended the program as a teacher of social studies teachers. (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Patrice Grimes, an associate professor in UVA’s Curry School of Education, attended the program as a teacher of social studies teachers. Her research focuses on the 20th-century history of African-American schooling in the South before mandated desegregation, and how educational history can inform current schooling policy and practice.

“As one who trains future and current educators in K-12 schools, I want to support teachers with the best information, tools and professional skills to tackle challenging and important topics, like the teaching of slavery, in their classrooms,” said Grimes, who is also an associate dean in UVA’s Office of African-American Affairs. “Teaching about slavery is important, in particular, because it is a step to understanding that past racial differences have divided our country. Without accurate, thoughtful and ‘hard teaching,’ students will continue to struggle to understand this history, and miss its connections to today.

“Schools, and public schools in particular, are one of the few arenas where we can, and should, be able to learn to engage, discuss and debate topics, based on evidence, in civil and respectful ways,” she said after the workshop.

The Illusion of Progress: Charlottesville’s Roots in White Supremacy

James Perla, managing director of the Woodson Institute’s Citizen Justice Initiative, described and demonstrated the website for the teachers at the Center for the Liberal Arts workshop.

A group of three local high school students and three UVA undergraduates worked with him last summer, he said, on creating “The Illusion of Progress,” starting before the second and third protests in July and August by white supremacists of the city’s vote to remove the statues of Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson from two downtown parks. (A temporary injunction has halted the removals.)

He said the students researched the history of Charlottesville and UVA, in the University’s archives and using online resources. The summer project, part of the Citizen Justice Initiative, was supported by the University’s Strategic Investment Fund.

The African-American business district known as Vinegar Hill was demolished in the early ’60s under urban renewal. (Photo from Vinegar Hill Appraisal Reports, 1960, Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority, Charlottesville, Va.)

“Throughout, we would have conversations and exercises to discuss the connections between historical materials they were researching and what they witnessed during the summer of 2017,” Perla said, “with the idea in mind that there’s so much beyond the Confederate statues as symbols that require our attention.”

Perla said it was obvious the teachers at the workshop had been thinking about how to teach this history when not used to doing so, and they seemed excited about applying these materials to their classes.

“You can work with your students,” Perla encouraged the teachers, “to envision and co-create a school system in which race and racism isn’t tacked on as an elective course or inserted as the unit on black history in the syllabus, but is central to an understanding of the American experience.”

Lisa Woolfork, a UVA associate professor of English who teaches African-American literature and culture, among other topics, accompanied Perla in the presentation, putting Charlottesville into the larger context and reviewing definitions of racism for the teachers. She said it’s a misunderstanding of racism that makes some people uncomfortable and defensive.

“The only way to get through this charged and traumatic history is to face this honestly,” said Woolfork, who is a project director for the Center for the Liberal Arts, helping plan some of the programs for K-12 teachers.

Lisa Woolfork, left, is a project director for the Center for the Liberal Arts. James Perla created “The Illusion of Progress” with students last summer. (Woolfork photo by Sanjay Suchak; Perla photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Perla suggested teachers develop action plans for anti-racist education, for their own personal learning and for their schools to enact systemic changes that will help students and society in the years to come.

A Framework for Teaching American Slavery

The speakers for the Teaching Tolerance project of the Southern Poverty Law Center provided the comprehensive guide, “A Framework for Teaching American Slavery,” part of its “Teaching Hard History” series of educational materials.

Maureen Costello, director of the Teaching Tolerance project, gave historic background – she previously taught history for almost 20 years – and Monita Bell, a senior editor there, facilitated a discussion about teachers’ concerns. They encouraged teachers to identify what about the topic might make them uncomfortable and then offered guidance about dealing with that.

“For example, we’ve heard from teachers that they don’t want to make their students of color feel ashamed and their white students feel guilty,” Costello said after the workshop.

Slavery “is central to our understanding of this country as an economic force in the growth of the United States, as the source of our beliefs about race, and as a major part of our history whose legacy lingers,” she said.

“After the program, several people remarked that what we did best was model confidence and comfort in talking about race,” she added.

Jessica Shim, who started teaching at Richmond’s William Fox Elementary School in January, said she has been able to take what she learned back to her classroom, reading primary sources such as letters by slaveholders and sellers and then using discussion strategies. She said her students were very responsive to the material.

“We had an amazing discussion about how primary sources can give us an insight into slavery that textbooks cannot give us,” she wrote in an email after the workshop.

Julita Brown-Dunn, a third-grade teacher at John Adams Elementary in Alexandria, has 26 years of teaching experience, and said the program allowed “open, honest and a much-needed discussion and discourse on the real, raw and true history of America.”

“I attended in hope of gaining resources and ideas of how to teach the ‘true’ history about slavery and the ‘forefathers’ and to see if this was a professional development or training that the Cultural Competence Coordinator for my district would be interested in bringing to Alexandria City Public Schools for teachers in fourth through 12th grades.”

She said she has been able to share the “Teaching the Hard History” framework and other resources with her colleagues, as well as the many insights gained from attending the workshop.

UVA Giving Teachers Education Tools

“The Center for the Liberal Arts has created a professional development model,” Grimes said, “where teachers can learn together and receive instruction that may not be available in their local schools or districts. It also offers the space where teachers can create their own networks to share their new knowledge and teaching strategies.

“By going directly to the teachers (and not disseminating ‘top-down’ from school districts), it has the potential to reach – and sustain – a broader, more diverse learning community over time.”

UVA has several programs addressing education about slavery to students of all ages through the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, as well as the Curry School of Education.

Grimes said she considers the Center for the Liberal Arts “an important partner that facilitates unique learning opportunities among researchers, educators and non-profit organizations. Through its sponsorship of programs like this, the center encourages us to move beyond our established networks to have greater impact in the communities that we serve.”

Luftig was gratified by the workshop’s proceedings.

“If anyone wants to be inspired, you should see 100 teachers learning about one of the hardest things you could teach – smart, dedicated people showing what is possible and committed to improving this country,” he said.

Media Contact

Article Information

March 30, 2018

/content/uva-program-arms-k-12-teachers-resources-slavery-and-racism