Researchers at the University of Virginia School of Medicine will seek to identify the genetic causes of schizophrenia as part of a major project funded by the National Institute of Mental Health to better understand how genetic variation in brain cells affects human health and disease.

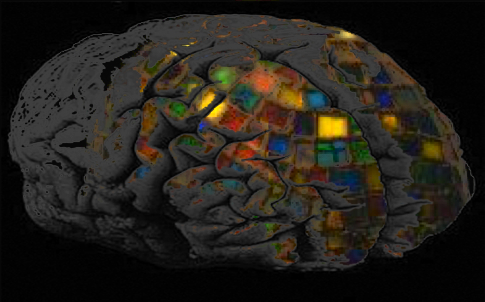

Mike McConnell of U.Va.’s Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics will use a cutting-edge technique known as single-cell genome sequencing to examine samples of donated brains, both from people who had schizophrenia and a control group of people who did not. The technique allows scientists to examine the genetic makeup of a single cell, a vital tool in the wake of the discovery by McConnell and his collaborators that the neurons in the brain are unexpectedly varied in their genetic makeup.

That variety of genomes within the brain – or “mosaicism,” as it’s called – could hold the secret to schizophrenia, and may explain why researchers have found it so difficult to determine the genes responsible.

“Right now, the genetic origins of schizophrenia are incredibly elusive,” McConnell said. “By looking at the brain and by understanding the genetic causes, we would hope to make better drugs or have better insights into therapeutic regimens to help these patients.”

McConnell will conduct single-cell sequencing with his former colleague Fred H. Gage of the Salk Institute. The work will be performed on selected cases from the world’s leading schizophrenia brain bank, the Lieber Institute for Brain Development at Johns Hopkins University. Human genome experts at the University of Michigan, meanwhile, will examine the genomes of pools of cells using what is known as bulk sequencing.

Each technique has its advantages, McConnell explained: “With bulk sequencing, you get better resolution of any event” – a notable genetic variation or other item of scientific interest – “that’s happening, but the event needs to be common. You can’t pick up rare events. You can pick up smaller changes, but the change needs to be shared among many cells,” he said. “Whereas in single cells, we don’t have quite the resolution, but we can pick up things that are one-off events, and rare and different. Since we don’t know which of those two differences it will be, we’re doing both.

“The idea is basically to look at well-paired samples of controls and schizophrenics and look at differences in the mosaic. Those differences could be gross differences … the type of thing we’ll pick up with bulk sequencing, or they could be differences that can only be detected through single-cell sequencing.”

The research at U.Va. and the other participating institutions is being funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Mental Health with a five-year grant that could top $11.5 million.

The participating researchers are setting up a major-data sharing initiative to make their findings quickly available to other researchers and the public, in line with the NIMH’s desire to make cutting-edge research accessible as soon as possible.

Media Contact

Article Information

May 6, 2015

/content/uva-shares-11-million-grant-probe-genetic-causes-schizophrenia