No matter the term paper topic, students have a world of research available at their fingertips, just a few keystrokes away via an online search engine. This semester, though, a new University of Virginia seminar is putting rare letters, journals and other historical artifacts directly in the hands of 16 undergraduate students, teaching them the scholarly value of investigating and interpreting primary sources.

Even as the U.Va. Library embarks on a three-year effort to digitize a cornerstone of its Special Collections in order to make it available for students, academics and researchers around the world, the new course, “Researching History,” acknowledges the need to continue teaching students the importance of taking their research directly to the source.

Whether it’s the liquor flask that Charles Dickens carried during his 19th century book tours of the United States, the roster of Confederate Army regiments with a preface written by a U.Va. faculty member referring to “the wicked government at Washington,” or the draft of a will written by Thomas Jefferson’s daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, indicating her desire to informally emancipate Sally Hemings and other members of Hemings’ family owned by her family, the primary sources used in the course has exposed Petrina Jackson’s students to a deeper understanding of the cultural and historical forces at play.

“That was one of the objectives of this seminar – to challenge the students and ask them, ‘Do you think the only way you can find information is through Google?’” said Jackson, head of instruction and outreach in U.Va.’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. “It’s introducing them to a form of research that they’ve likely not experienced, to get them taking baby steps in the direction of thinking more like a historian.

“Most people will go through their four years of college without ever encountering any primary source research. But it brings you head and shoulders above your peers when you are able to introduce this type of research into your scholarship. It’s important to be able to understand where someone who’s already interpreted things for you is coming from. But it’s another thing to be able to use the skills that you have to interpret historical documents.”

Special Collections holds more than 16 million manuscripts, archival records, rare books, maps, photographs and other items available for review. For the first- and second-year students enrolled in Jackson’s seminar, the library offered a bounty of materials for an eclectic group of student exhibitions presented to the public on Tuesday afternoon.

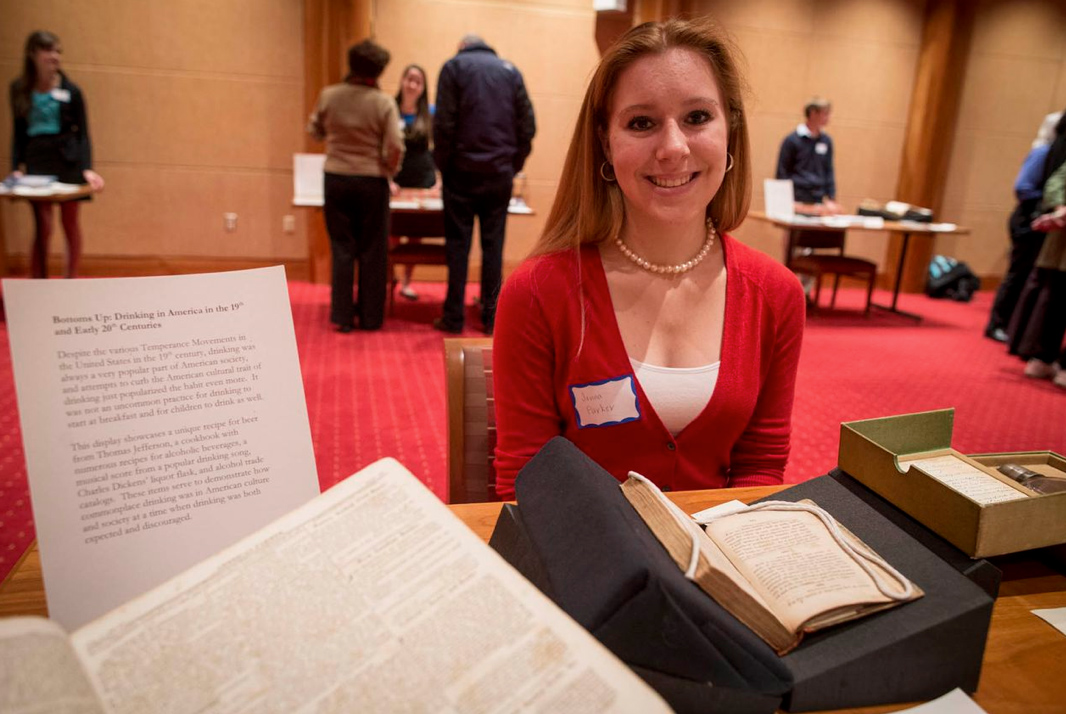

In addition to Dickens’ flask, first-year nursing student Jenna Parker found Jefferson’s brewing recipe for persimmon beer in the weekly periodical, “The American Farmer.” That fueled her interest in mounting an exhibit titled, “Bottoms Up: Drinking in America in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries.”

“I’m used to just Googling everything and didn’t have any idea how to use primary sources for research before this class,” Parker said. “It’s so interesting. I had no idea there was all this stuff in Special Collections.”

First-year student Elvera Santos knew she wanted to organize an exhibit on the historical debate over Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings, but like Parker, had no previous experience working with primary sources. With the assistance of Special Collections librarians, Santos examined the diary of a colleague of Jefferson’s colleague, John Hartwell Cocke,, who wrote of “this damnable practice” by Jefferson and other Virginia slave owners of keeping a slave mistress.

She also examined letters by one of Jefferson’s granddaughters and others who discounted the possibility that Jefferson had fathered children with Hemings.

“I’ve seen movies, I’ve read a book about it, but it’s completely different to see firsthand what people at the time thought and how it impacted scholars who wrote about it,” Santos said. “It was much more impactful.”

Several of the students enrolled in Jackson’s seminar indicated they intend to major in history or the humanities. Even those intending to focus on the sciences or to apply to the McIntire School of Commerce, however, recognized the value of mastering historical research.

“It would have been completely different researching University of Virginia students who served in the Confederate Army without primary sources,” pre-med major Corey Bothwell said. “It would be a 180. No comparison, because when you rely on secondary sources to make the connections for you, you wouldn’t get that deeper understanding that you can get from examining regiment rosters and other documents yourself.”

First-year student Megan Strait admitted it was daunting at first to take on her research topic: John Armstrong Chaloner, a Gilded Age heir to the Astor fortune who was falsely committed to a New York insane asylum by his family before escaping to Virginia.

Strait’s exhibit included a neighbor’s testimony, from a proceeding in the Virginia court system, that Chaloner was “perfectly sane, if any man is,” as well as Chaloner’s book proclaiming his ability to tap into his unconscious through a sixth sense he called “The X-Faculty.”

“The product at the end is so much richer,” Strait said of working with the primary sources. “It’s a thousand times better an experience than just going online and finding something to write about. It’s a little bit more work, but it’s a lot more fun.”

Media Contact

Article Information

November 20, 2013

/content/uva-students-learning-dig-special-collections-historical-research