During the Civil War, the University of Virginia was predictably a hotbed of the Confederacy, but the flame of Unionism flickered faintly.

“More than 3,000 UVA alumni fought for the Confederacy, and approximately 90 percent of the student body enrolled in the fall of 1860 enlisted into Confederate military units by the end of 1861,” said William B. Kurtz, managing director and digital historian at UVA’s John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History.

“While support for the Confederacy was overwhelming, however, it was not unanimous. History graduate student Brian Neumann, working with the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History, has found more than 50 alumni who fought with the Union forces, as well as a biology professor who served with the 8th Ohio Artillery. And Amelia F. Wald, a Sewell Undergraduate Intern at the center, detailed three Union veterans from Indiana who came to UVA for medical school after the war.”

Neumann sifted through the records of the 6,700 students who had attended the University before the Civil War and cross-referenced them with military data and other databases, such as Ancestry.com.

“UVA’s Civil War story is overwhelmingly Confederate, but there were Unionists in the mix – a small group whose presence has been almost completely invisible,” said Gary W. Gallagher, former director of the Nau Center and Neumann’s adviser. “Brian Neumann’s research will help recover the story of these students, which will in turn underscore the fact that Virginia remained divided in significant ways during the secession crisis.”

Kurtz said the center first explored the UVA Unionist question in 2016, but had focused on African-Americans from Albemarle County who fought with the Union forces. Then Neumann, who was preparing a thesis on Southern Unionism, stepped forward.

“Over the course of the summer of 2017, he looked through the catalogues for 1825-26 through 1860-61, finding more than 50 students who served in the Union Army or Navy,” Kurtz said. “An undergraduate and I have been looking through post-war catalogues for even more, which led to the discovery of one professor, biology chair Albert H. Tuttle, and a handful of men from Indiana who came to UVA after the war for medical degrees.”

With technological help from the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, the center is continuing its search for Cavaliers in blue, entering them into a database and gathering letters, diaries, pension files and other primary sources from archives across the United States.

Neumann said he had expected the Unionists to be Northerners, but he found that two-thirds of them were from the South.

“Most UVA students favored secession,” he said. “In early 1861, they flew a Confederate flag over the Rotunda and burned effigies of Unionist generals on the Lawn.

“But a few students remained loyal to the Union. There were even four Unionists in the class of 1860-61, the last one before the war. Some of these Unionists were from border states, such as Maryland and Missouri, but others were from the Confederate South, such as Virginia, Texas and South Carolina.”

Neumann went through their letters and writings and found that many Unionists took their positions because the unity of the country was important to them. Not all the Southern Unionists were opposed to slavery.

“Some Southern Unionists ultimately supported emancipation for economic or military reasons. But many others remained pro-slavery and supported the Union because they believed slavery would be safer in a united country,” he said. “Their Unionism was often practical – they wanted to protect their families and preserve slavery and social order – but it was also ideological. They viewed the Union as the last bastion of liberty, and they were afraid it would be destroyed.”

He cited James O. Broadhead of Charlottesville, who attended UVA from 1835 to 1836. He was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel in the 3rd Missouri Cavalry and served as provost marshal general of the Department of Missouri. Broadhead owned at least two slaves and served in the Missouri Secession Convention, where he argued that secession would destroy slavery because the state would lose federal protections such as the Fugitive Slave Law. He was quoted in contemporary newspaper accounts as saying “every damned Abolitionist in the country ought to be hung.”

Others believed in emancipation, such as Bernard Gaines Farrar Jr., the colonel overseeing an African-American regiment. Born in St. Louis in 1831, he attended UVA during the 1850-51 school year. His parents were slaveowners, but by 1854, he supported “free soil” politics, which sought to block the westward expansion of slavery; in 1860, he voted for Lincoln.

He enlisted in the Union Army on May 5, 1861, and served as aide-de-camp to Gen. Nathaniel Lyon and later Gen. Henry Halleck. He served as colonel of the 30th Missouri Infantry and participated in the Vicksburg campaign. On Sept. 12, 1863, he raised an African-American regiment, designated the 2nd Mississippi Heavy Artillery (African Descent), which was eventually re-designated the 6th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery. They were stationed mostly in Mississippi.

Neumann said UVA students were not unique among the small contingent of pro-Union sentiment in the South.

“They wanted to preserve the Union and American exceptionalism,” he said. “They believed there were certain material and political benefits to the Union, such as all white males being able to vote. There were a lot of places in the world where that was not the case.

“Several of these men took part in secessionist conventions and voted against secession,” he said. “Some came from divided families, some had a sense of duty because of prior military experience.”

While Unionists during the war, some soured on the ramifications of emancipation and the fight for black civil rights during Reconstruction.

“The wartime Unionist coalition was deeply divided, especially over issues of emancipation and how to treat Confederates,” Neumann said. “Some Unionists simply wanted to return to the status quo – restoring as much of slavery as possible and restoring all political rights to former Confederates. These Unionists often felt betrayed by Radical Reconstruction and eventually allied with former Confederates to help undermine Reconstruction. James Broadhead fell into this category.”

Other Unionists, however, wanted to punish former Confederates, especially the planter class. During Reconstruction, this group eventually accepted emancipation and African-American suffrage as a way to punish Confederates and build a Southern Republican Party. These Unionists often faced violence and intimidation from the Ku Klux Klan, and after Reconstruction they were forced out of power as “redeemer” governments took control of Southern states.

One Unionist who rejected the Radical Republican Reconstruction efforts to punish Confederates was William Fishback, who attended UVA from 1852 to 1855, studying ancient languages. He read law in Richmond and practiced briefly in Springfield, Illinois, where he worked for a time with Abraham Lincoln. Fishback moved to Arkansas for his health, spoke out against secession and escaped to Missouri after hostilities had broken out and his life was threatened. He eventually came back to Arkansas in 1863 after the Union Army had seized the territory; he recruited 900 men to fight for the Union, though he never led them in battle.

Fishback opposed efforts to disenfranchise the former Confederates and published a newspaper, “The Unconditional Union,” in which he railed against the elements of Reconstruction to which he was opposed. He served as governor of Arkansas from 1892 to 1894, but failed to be re-elected. He stayed active in politics, but when he died in 1903, the UVA Alumni Bulletin made no mention of his passing.

“UVA Unionists’ experiences during the war varied dramatically,” Neumann wrote in an entry for the center’s blog. “After the war, however, they shared a common obscurity at UVA. As the University glorified its Confederate past, it constructed a war-time narrative of unity and principle that left no place for its Union soldiers and sailors.”

In 1869, Marion Goss and Joseph Noble, both from Parke County, Indiana, and both veterans of the 149th Regiment, Indiana Volunteer Infantry, enrolled in UVA’s School of Medicine; Goss later convinced fellow 149th veteran Jacob Mater to join them. Goss and Noble had been influenced in their choice of school by Dr. John Wilcox, an 1850 UVA Medicine graduate.

“Despite the anti-Northern hostility, at UVA Goss and Noble dedicated themselves to their studies, determined to establish reputable medical careers,” Wald wrote at the Nau Center’s website. “They graduated in 1870, with Noble at the head of the class.”

The complete story of Goss, Noble, Mater and Wilcox is available in two parts, here and here.

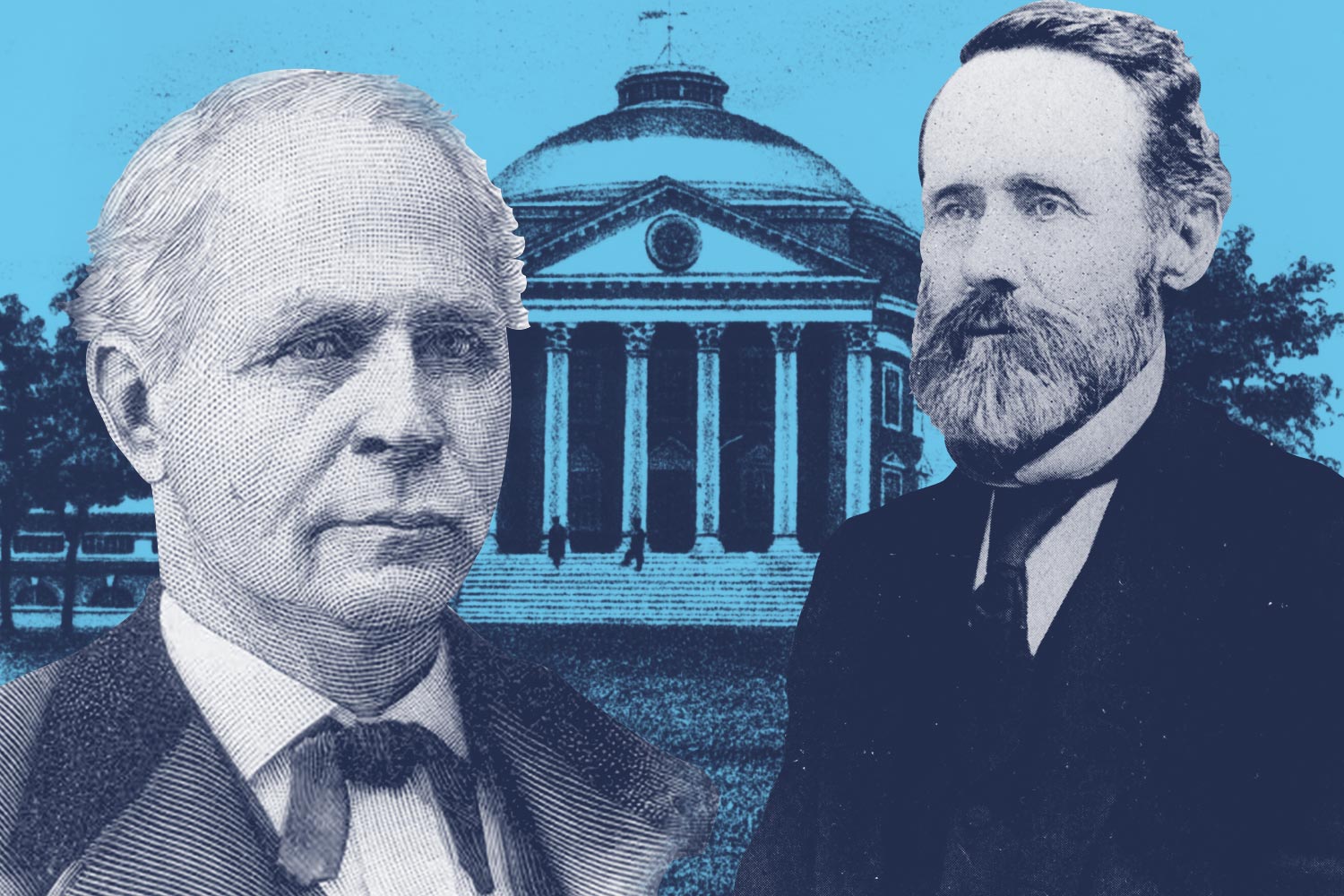

Unionists were scarce among the faculty, as well, though one, Albert Henry Tuttle of Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio, was hired in 1888 to chair of the biology department. He had served in the Union Army as part of the 8th Ohio Artillery from July to September 1864. After the war, he graduated with a Master of Science degree from Pennsylvania State College in 1870, taught zoology and geology at Pennsylvania State University in 1872, and then at Ohio State University from 1873 to 1888. From there, he came to UVA and remained until he retired in 1913. One of the Alderman Road dormitories bears his name.

“It was ‘unusual’ to hire a Unionist in the sense that he was apparently the only one,” Neumann said. “But it doesn’t seem to have provoked any discussion. No one ever seemed to mention it, and they may not have even known.”

The Alumni Bulletin went into great detail on the military service of the Confederate veterans on the faculty when they retired or died. When Tuttle retired, there was nothing written in the Bulletin about his service in the Union Army.

Tuttle was still a professor at the University when UVA sponsored a reunion of Confederate veterans who attended school from the 1860-61 to 1864-65 school years, as part of the three-day graduation celebration in June 1912. Invitations were sent to the 119 surviving Confederate veterans, of whom one died soon after, and at least 32 attended the ceremonies on Grounds. They each were given a medal. There were addresses by University President Edwin Alderman, some of the veterans, and professor J. W. Mallett, one of the organizers, who spoke on Gen. Robert E. Lee. Accounts of the reunion in the Alumni Bulletin again made no mention of UVA’s Union soldiers.

A year after the reunion, Brigadier Gen. Charles Irving Wilson, who attended UVA from 1855 to 1857 and served as cavalry surgeon in the Union’s famed Army of the Potomac, died. Although the Alumni Bulletin actually published a short biography in his honor, a local paper, the Staunton Daily News, took the opportunity to chide UVA for its “grave oversight” in not paying more attention to all of its “sons who were in the Federal forces.” Although the Bulletin acknowledged that “no complete list” had been compiled of its Unionist alumni, neither its staff nor anyone else at the University did anything further to identify its Union soldiers and sailors.

More details are available at the Nau Center’s blog.

Media Contact

Article Information

September 20, 2018

/content/uvas-civil-war-story-not-all-confederate