The saying goes that “what is old is new again.” Many elderly Americans are hoping that proves true.

According to Forbes Magazine, house calls made up 40 percent of U.S doctors’ patient encounters in the 1940s before that figure started to drop off in the 1960s.

A new study involving the University of Virginia finds that older, frail Americans – up to 4 million of them – live at home, but are not getting the health care they need. Aaron Yao, an assistant professor in the Department of Public Health Sciences in UVA’s School of Medicine, said bringing back the house call can greatly help this population.

“We don’t have enough home-based medical care,” Yao said. “In the good ol’ days, doctors always go to patients, but as the technology is getting more advanced, and medicine gets more specialized, our health care is more hospital and office-centered.”

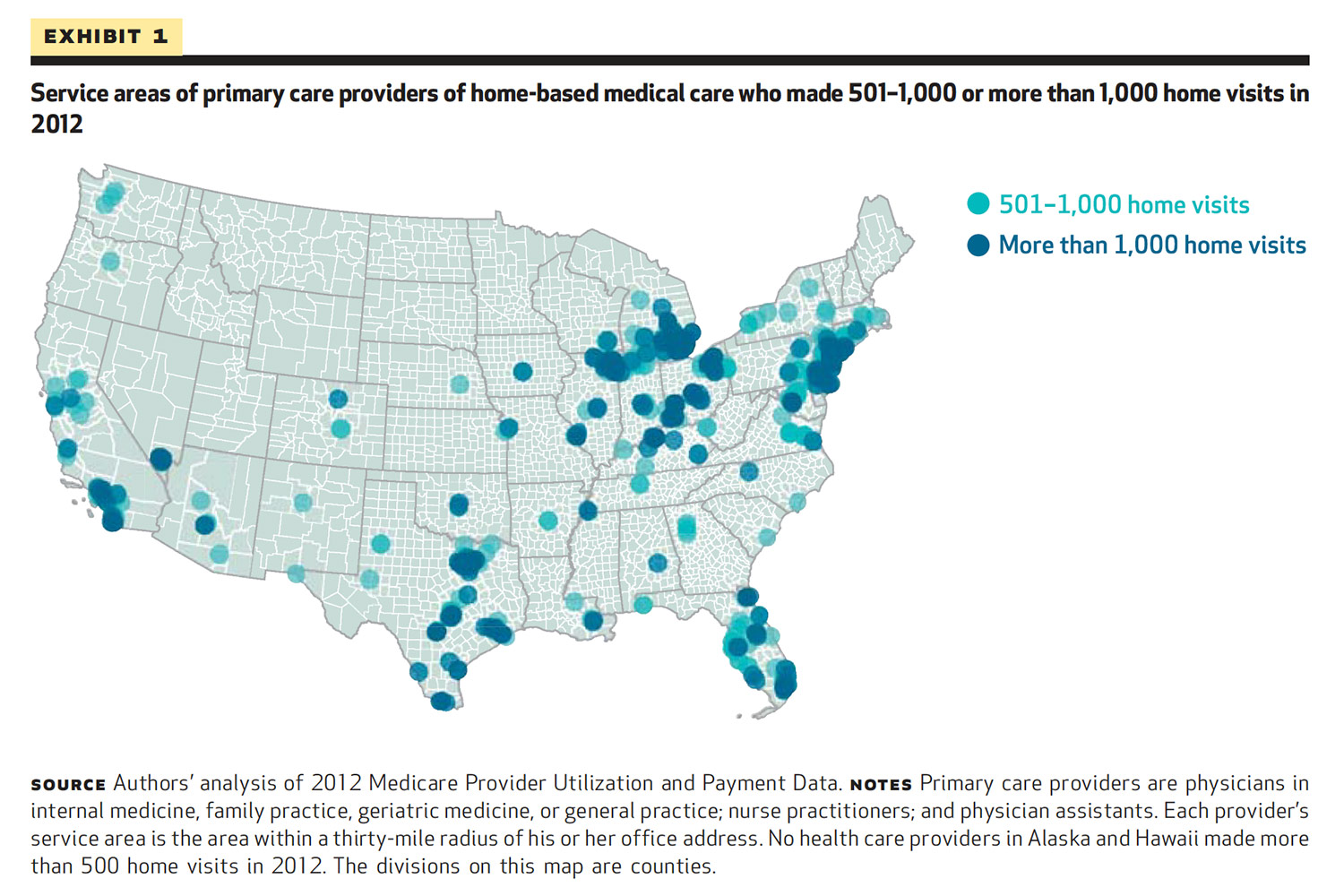

Yao and his colleagues analyzed 2012 and 2013 Medicare payment data to track home visits around the country. They found that geographical location plays a large role in whether or not a patient can be seen in his or her home. Most live more than 30 miles from care providers, putting them out of reach from doctors and nurse practitioners who typically do not travel that distance to see patients.

This map, published with the findings, shows the geographic distribution of home-based health care delivery across the country in 2012. No health care providers in Alaska and Hawaii made more than 500 home visits in 2012.

The new study also highlights another problem: the United States is facing a huge shortage of doctors who make home visits. Yao said less than 1 percent of primary care physicians routinely make house calls.

According to the study, published this month in Health Affairs, a major health policy journal, “About 5,000 primary care providers made 1.7 million home visits to Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in 2013, accounting for 70 percent of all home-based medical visits. Nine percent of these providers performed 44 percent of visits.”

The current fragmented model of health care does not serve the full scope of needs of homebound Americans, which results in large expenditures because of hospitalizations and visits to the emergency department, Yao said.

With the U.S. continuing to age, caring for patients in their homes will save money because it prevents people from ending up in the emergency room or the hospital, he said. “If I am old and have problems, but I have my symptoms controlled, then I probably won’t need to call 911. From the society’s perspective, it actually saves a lot of money.”

The study found that the homebound elderly account for more than half of the costliest 5 percent of patients. But pushing for more home-based medical care is not just cost-effective, “it’s also about quality of life,” Yao said.

So how can patients receive care in their homes? Yao recommends they look for home-based medical care providers in their communities, and ask their current doctors to help find in-home care. He also suggested doctors consider adding home-care visits to their schedule, even if for just one day a week or month.

“It’s a more patient-centered model,” he said, adding that health care professionals who do this have huge job satisfaction. “They love their jobs,” he said.

Media Contact

Article Information

August 16, 2016

/content/new-study-finds-homebound-elderly-patients-missing-out-home-care