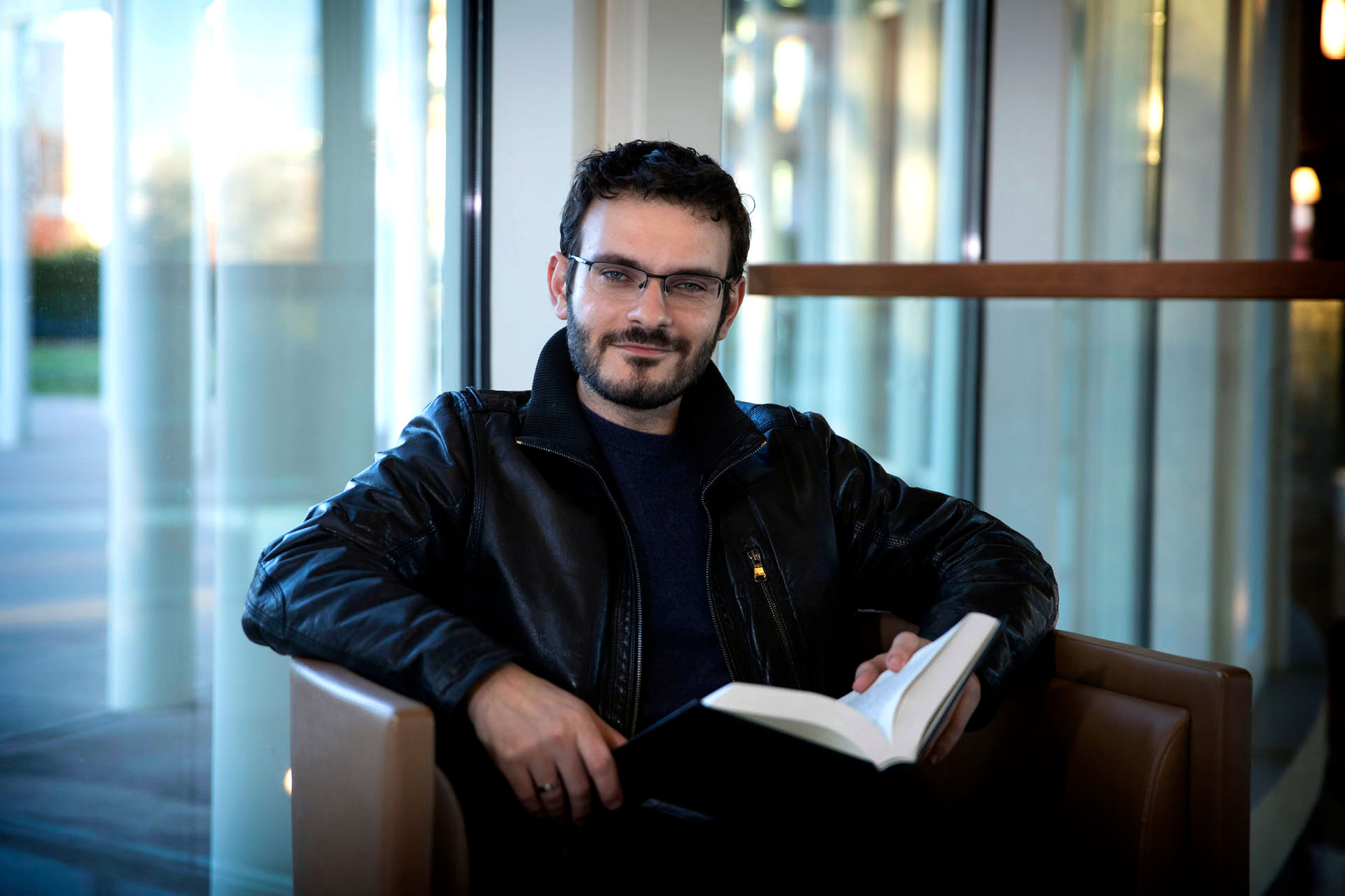

In his second year at the University of Virginia, Murad Idris is challenging his students to critically examine the established norms of political thought. In particular, the assistant professor of politics is focused on the concept of peace and how it’s been wielded throughout history.

His current book project, “Disturbing Peace: Athens, Islam and the West,” explores the idea of universal peace and how peace is discussed across major texts in the Western and Islamic traditions. It traces how common claims, like the idea of waging war for the sake of peace, recur in the works of Plato, Thomas Aquinas, Thomas Hobbes, Abu Nasr al-Farabi, Ibn Khaldun and other prominent philosophers.

Through his research, Idris has also begun to trace the roots of the phrase “Islam is peace” by examining variations on this claim in modern philosophical discourses, as well as older competing claims and translations of the word in genres like lexicography.

Idris recently met with UVA Today to explain his work and how it contributes to modern political understandings.

Q. What are the dominant philosophical understandings of peace?

A. There are a number of competing understandings. Some simply say, “Peace is the absence of war.” Others, like Plato, will say peace requires friendship, law and a particular political form. With Immanuel Kant, peace quickly turns into security with a certain political economy. You also see that with Hobbes, a turn away from friendship toward security.

Part of what I’m interested in is not just that there are different understandings of peace, but that there’s dominant threads or maneuvers that weave together these understandings. They’re each held together by a series of additives, what I call a parasitical structure. Whether it’s friendship or security, peace is given content through its relationship to other ideas, ones that end up rewriting it or even replacing it.

There are three general positions that people hold around peace, even today. One is that peace is something that we need to strive for and it’s attainable. Another position holds that peace is an apolitical idea, and we need to be concerned with order, security and things of that nature. The third is that peace is this absurdly utopian idea. It’s a kind of impossible fantasy.

The problem with each of these perspectives – peace as a goal, peace as mere rhetoric and peace as a fantasy – is they end up shielding the idea of peace from any kind of critique. That is problematic to me, especially since there have been so many wars sanctioned by appealing to peace.

Q. What have you uncovered by critically examining the historical concept of peace?

A. By looking at the historical development of peace, we can get a sense of its relationship to violence, war and hostility. It is neither simply the absence, or even the reversal, of war and violence. The ideas we end up associating with peace – like security, law or friendship – are often elaborated with reference to some specific enemy, one that we think can’t participate in peace. When we’re talking about peace we are often saying implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, “And by peace we of course mean something that can’t happen with this other group.” The assumption is that peace naturally belongs to this ‘we,’ and that even wars waged by that which we call ‘we’ are peaceful.

Q. How does your research relate to the linguistic construction of Islam as peace?

A. In addition to the common claim that war is for peace, another claim that we hear repeated time and again is “Islam is peace” or the retort, “Islam is not peace.” I’m interested in what these kinds of claims make possible, in terms of people’s imagining of global politics, religion and politics, and Islam specifically.

These claims have a history. They don’t just appear out of nowhere. I started thinking about claims that are related in form to “Islam is peace,” and the common refrains that fill in the blank after “Islam is x.” You get phrases like “Islam means submission,” “Islam was spread by the sword,” “Islam is from the desert” or “Islam needs a Luther.” These are all familiar tropes that have had a fairly long life.

I’m interested in writing the lives of these claims and how they constitute Islam in language, as they travel across languages and regions, appearing, for example, in the Reformation and Enlightenment, and in changed form, in 19th and 20th century European scholarship about what Islam means and how it should be translated. Each of these claims and linguistic constructions was political. These and alternate claims appear in 20th-century Arabic thought about Islam, the religion and the word, and its relationship to the Arabic triliteral s-l-m root that forms the basis of words like salam and islam, which are usually translated as “peace” and “submission” respectively. We also see other constructions in earlier Arabic discourses, and these are really different epistemic structures.

Q. What do you hope your students take away from discussions of peace and its place in political history?

A. The way that I tend to think about political theory is that it offers us different ways of understanding the world and trying to bring order to it. A political thought is a way of imagining and organizing the world. Each always contains different kinds of erasures. Each also makes only a series of specific things visible and possible. So when we look at a dominant political language, grammar or vocabulary, and especially at the concepts that have the greatest currency today, I want my students to ask why they have this dominance and what we’re missing if we take them as natural understandings of the world.

Editor’s note: This is another installment in an occasional series profiling members of a generational wave of new faculty members at the University of Virginia.

Media Contact

Article Information

November 29, 2016

/content/professor-examines-ideal-peace-and-its-use-political-tool