For more than 10 years, University of Virginia alumnus Kenneth Holland has played a significant role in rebuilding higher education in war-torn Afghanistan. Now, he is beginning a new challenge as president of the country’s most prestigious university, American University of Afghanistan, or AUAF.

Holland, who earned a master’s degree in government from UVA in 1971 before completing his doctorate at the University of Chicago, relocated to Kabul to begin his tenure on June 1, just one day after the city’s biggest terror attack in recent memory. A suicide bomber detonated a bomb from a delivery truck, killing 150 people, including an AUAF professor and an alumnus.

The university itself was directly targeted when militants stormed the campus in August 2016, killing 15 people, including seven students and one professor.

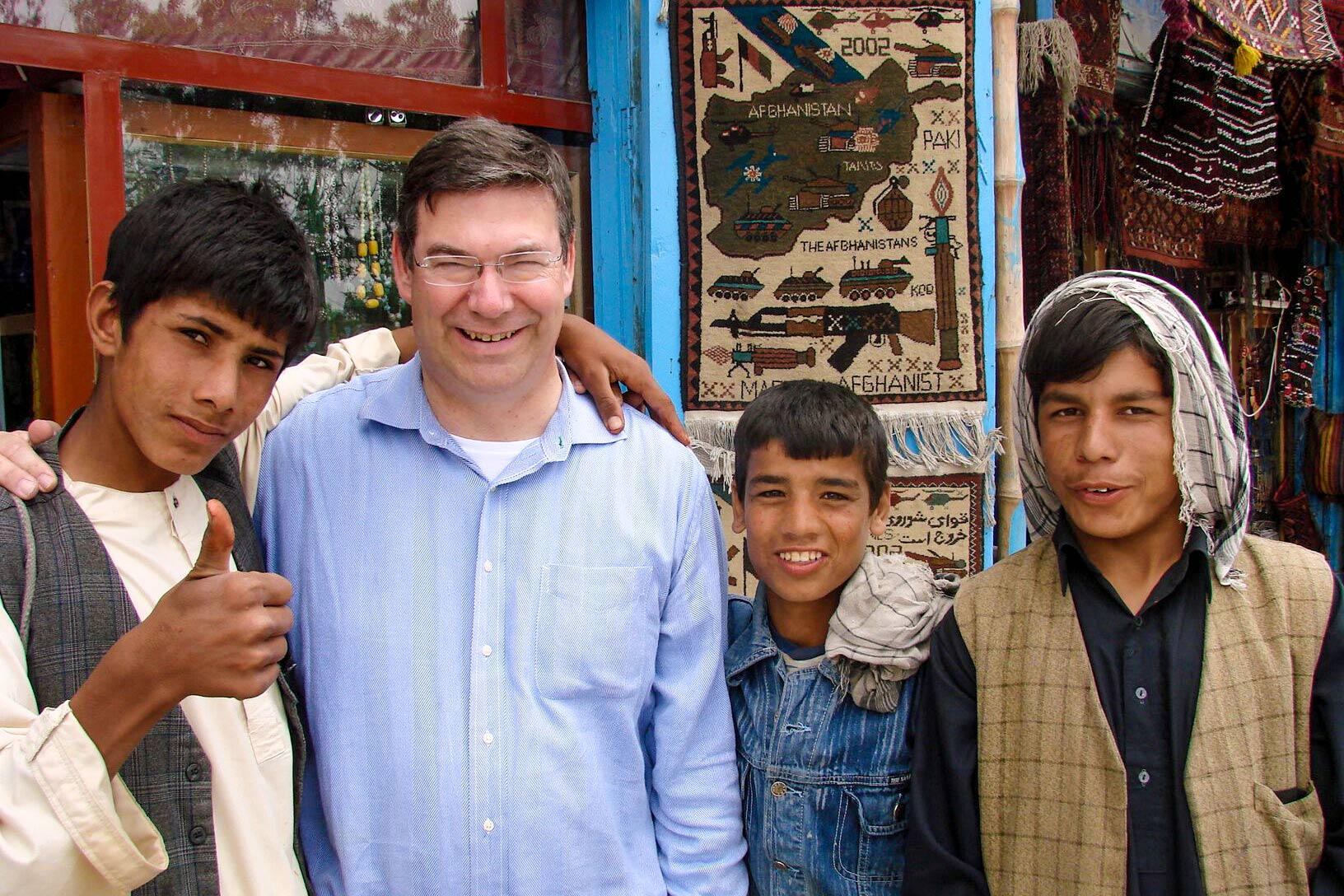

Holland, left, with Yar Ebadi, Holland’s former colleague at Kansas State University who first introduced him to Afghanistan.

Holland sees his work at AUAF, and higher education in general, as an important means of fighting such extremism and bringing peace and prosperity to a country hobbled by decades of war.

“Without a strong higher education system, the country cannot properly manage itself or develop the resources that it has,” he said.

Holland first began working in Afghanistan in 2006 while he was the associate provost for international programs at Kansas State University. Yar Ebadi, then dean of Kansas State’s business school, requested Holland’s help in rebuilding his alma mater, Kabul University, and Holland managed the revitalization of the school’s engineering college and English department. Over the next decade he returned to Afghanistan 60 times, working with the U.S. State Department and other international aid and nonprofit organizations to rebuild universities around the country. He also served as a rule of law adviser for the International Security Assistance Force, a NATO-led effort to train and fight alongside the Afghan National Security Forces.

Holland and his wife Julie now live in Kabul.

When the AUAF presidency came open earlier this year, it felt like a natural fit. He decided to leave his position at Ball State University, where he was a professor of political science and executive director of the Center for International Development.

“I saw it as continuing the work I have been doing for so many years in Afghanistan,” Holland said.

UVA Today spoke with Holland about the changes he hopes to enact as president, the challenges of his new job and the road ahead for Afghanistan.

Q. What differentiates the American University of Afghanistan from other schools in the country?

A. Until now, I had only worked with public universities in Afghanistan, which base their curriculum, teaching methods and structure on models influenced by Europe and the Soviet Union. AUAF is a private, not-for-profit institution based on the American model of higher education, with a liberal arts curriculum designed to encourage critical thinking.

My time at UVA helped shape my conception of that structure; I view UVA to be a real model of the best of American education and of what we hope to do here.

We partner with some of the United States’ best universities, our courses are taught in English and many of the professors travel to Kabul from the U.S. It is considered to be the best higher education institution in the country, and our students are some of Afghanistan’s brightest young people. They are very valued in the job market, and are typically hired right away by government ministries, international organizations and private businesses.

Q. What role can universities like AUAF play in Afghanistan’s recovery?

A. Afghanistan has one of the highest illiteracy rates in the world, at above 60 percent for the general population and higher for women. The country has tremendous natural resources in agriculture and mining, with huge lithium, iron and copper deposits, as well as great tourism potential. To make use of those resources, they need a strong, educated workforce. Higher education can provide that and can help alleviate the extreme poverty that fuels a lot of the instability and violence here.

Our students are becoming Afghanistan’s next leaders in business and government. One of our graduates is currently the ambassador to the United States. Our faculty love working with the students, because they are so eager to learn, and because they can see the direct outcome of their teaching in the prosperity of the country. What they do here makes a difference.

Q. How are you and your staff handling threats of terrorism, heightened after last year’s attack and recent violence in Kabul?

A. After the attack last August, the United States Agency for International Development helped the university upgrade its security operations and hire a private security company. I would say we now have embassy-level security, with complete control over who enters and leaves the campus. My wife Julie and I live on campus, as do many of our students and international faculty. Becoming a part of that residential community has been very pleasant.

Q. As president, what changes do you hope to implement at AUAF?

A. I recently presented my vision to the university’s board of trustees. Among other priorities, I would like to create a program in leadership studies patterned after a program at Kansas State. I would also like to establish Afghanistan’s first doctorate with a Ph.D. program in business. Right now, doctoral students have to leave the country to earn a Ph.D. That is often difficult, especially for women. If we helped make doctoral degrees available in Afghanistan, we could encourage more students to pursue graduate degrees, and keep more doctoral students in the country.

Media Contact

Article Information

June 22, 2017

/content/qa-alumnus-kenneth-holland-leads-resurgence-higher-ed-afghanistan