University of Virginia researchers have for the first time revealed brain imaging evidence that supports what experts have long hypothesized: that people with strong relationships report better general health than those who do not.

Researchers in professor James Coan’s clinical psychology lab zeroed in on the hypothalamus, which regulates stress hormones, to reveal how the brain responds differently to the threat of electrical shock when a trusted loved one is near.

While lying in a brain scanner, subjects encountered three scenarios: Holding the hand of a relational partner, holding the hand of a stranger or holding no hand at all. In each scenario, a screen in the machine visible to the test subjects displayed a blue circle, which test subjects were told corresponded to no threat of shock, or a red ‘X,’ which they were told indicated a 20 percent chance that they would receive a minor shock to their ankle. Indeed, shocks were delivered 20 percent of the time.

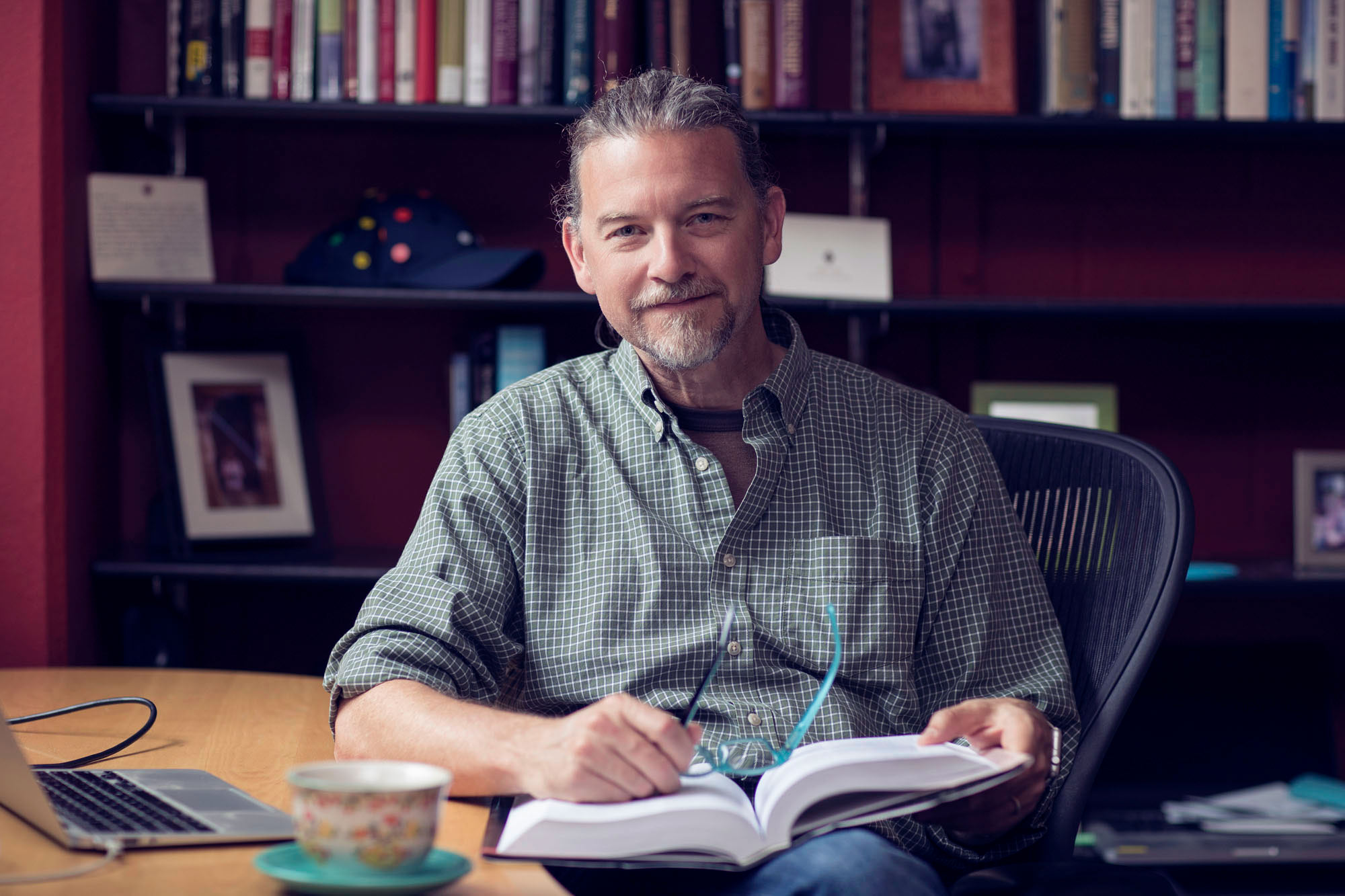

Psychology professor James Coan leads UVA’s Virginia Affective Neuroscience Laboratory. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

In addition to the imaging, study participants filled out a standardized health survey in which they rated their general health. Although the survey is subjective, Coan said it correlates strongly with objective measures derived from physician reports.

“What we found was that the less active your hypothalamus was when you are under threat of electric shock in the brain scanner while you are holding the hand of a relational partner, the better general health you report,” Coan said.

Nothing similar was found during stranger handholding, or while subjects faced the shock threat while alone.

“This is the first time this hypothalamus-health link has ever been reported using data from the functioning brain. The reason this is really important is that people have hypothesized, literally for decades, that we should find this, but no one has ever found this until now.”

The study, which is part of a longitudinal inquiry into how relationships affect human health, involved 75 people from the Charlottesville community. Nearly 40 percent of participants were African-American; all came from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds. “One of the things that distinguishes this study is that it’s fairly well representative of Charlottesville and the country,” Coan said.

The researchers collected data over the course of four years. The study results are being published in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine.

What the researchers were looking for in using magnetic resonance imaging was increased blood flow to the hypothalamus.

“The reason more blood is flowing to a structure is because that structure has eaten up a bunch of resources and it needs to be replenished,” Coan said. “It’s metabolized a bunch of material and it needs more food, if you will.”

When the body is under stress, the brain releases hormones like cortisol and epinephrine into the bloodstream. The trouble is the flow of those hormones removes resources from the immune system. In the long term, that cycle can lead to poor health.

“When our social support system inhibits our hypothalamus’ response to stress, we release fewer, potentially destructive stress hormones and have a stronger immune system,” Coan said.

Previous research has shown that frayed social networks can have deadly consequences. “We have all these public service announcements about exercise and not smoking, but social isolation is more deadly than all of those things,” Coan said. “The more socially isolated you are, the more likely you are to die of anything at any time, no matter where you live or what culture you inhabit.”

So simple hand-holding can be very impactful.

“Having that hand to hold signals that you have resources – you have safety – so any particular stressor is just not as stressful as it might have been,” Coan said.

“What we are finding here is that if our relationship is good and we are with someone we trust, we can say, ‘Hypothalamus, you don’t have to work as hard right now. Yeah, there is a threat, but chill out – the threat is not as threatening as if you were alone.’ Your friend will help you deal with that threat; therefore you can work less hard to deal with it, and that savings will keep you healthier in the long run.”

Media Contact

Article Information

May 26, 2017

/content/shocking-new-research-finds-friendships-are-key-good-health