A new technique for precisely targeting molecules within cells is paving the way for medicines that are free of side effects.

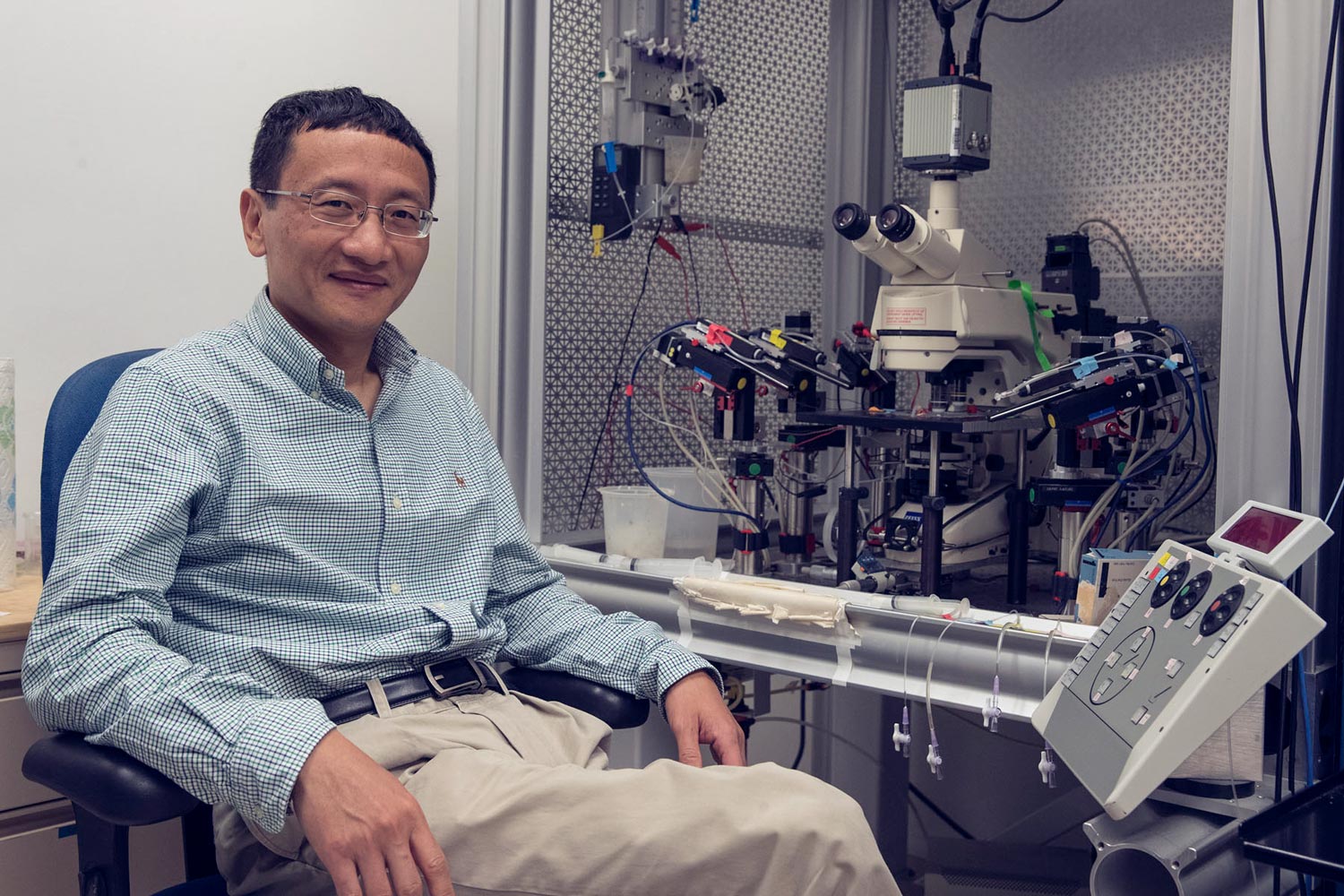

Researcher J. Julius Zhu of the University of Virginia School of Medicine and his colleagues have developed a way to manipulate molecules from compartment to compartment within individual cells. Amazingly, the same molecules do different things depending on their location, the researchers determined. By manipulating the molecules, scientists can determine exactly which locations to target, while avoiding locations that would cause harmful side effects.

“The problem with side effects is caused because you just could not distinguish the molecules doing different things in the same cell,” Zhu said. “If you blocked a molecule, you blocked it regardless of what it was doing. And that usually has unwanted side effects. Almost every drug that can treat disease has side effects, either major or minor, but usually they always have something.”

Until now, drugs have targeted molecules in a very general way. If a molecule was thought to be harmful, researchers might try to develop a drug to block it entirely.

But Zhu’s new work highlights the downside of that shotgun approach. A molecule might be causing problems because of what it’s doing in one part of the cell, but, at the same time, that same molecule is doing something entirely different in other parts – perhaps something tremendously important. So shutting it down entirely would be like trying to solve the problem of traffic congestion by banning cars.

Now, rather than crudely trying to block a molecule regardless of its many functions, doctors can target a specific molecule doing a specific thing in a specific location. That adds a new level of precision to the concept of precision medicine – medicine tailored exactly to a patient’s needs.

Zhu, of UVA’s Department of Pharmacology, thinks the technique will be useful for many different diseases, but especially for cancers and neurological conditions such as autism and Alzheimer’s. Those, in particular, will benefit from a better understanding of what molecules at what locations would make good targets, he and his colleagues note in a new paper sharing their technique with other scientists.

The technique will also speed up the development of new treatments by letting researchers more quickly understand what molecules are doing and which should be targeted.

“The idea [behind the technique] is actually very simple,” Zhu said. “But it took us a lot of years to make this thing work.”

Zhu and his team have described the new technique in the scientific journal Neuron. The research team consisted of Lei Zhang, Peng Zhang, Guangfu Wang, Huaye Zhang, Yajun Zhang, Yilin Yu, Mingxu Zhang, Jian Xiao, Piero Crespo, Johannes W. Hell, Li Lin, Richard L. Huganir and Zhu.

The work received financial support from groups in America and abroad, including National Institutes of Health grants NS036715, NS065183, NS089578, NS078792, NS053570, NS091452, NS094980, NS092548 and NS104670.

Media Contact

Article Information

July 5, 2018

/content/uva-develops-way-create-medicines-free-side-effects