The University of Virginia’s first professor of natural sciences appears in an 1842 portrait as a slender, balding man with wisps of hair combed across his forehead. Slightly stooped, his face was wan from a childhood bout with smallpox. Exposure to the chemicals that were among the tools of his trade contributed to his early death at 47. During his relatively short life, however, John Patten Emmet would imprint American education, influencing how students learned in science labs and doing so from the heart of Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village.

Professor Emmet believed that the students should do the experiments themselves, which was a change from the practice of the time of teaching by demonstration.

“Professor Emmet believed that the students should do the experiments themselves,which was a change from the practice of the time of teaching by demonstration,” said Brian Hogg, senior preservation planner in the Office of the Architect for the University.

Today, interest in Emmet and his early experiments and pedagogy is surfacing anew with the discovery of a hidden chemical hearth in the wall of the Rotunda’s Lower East Oval Room.

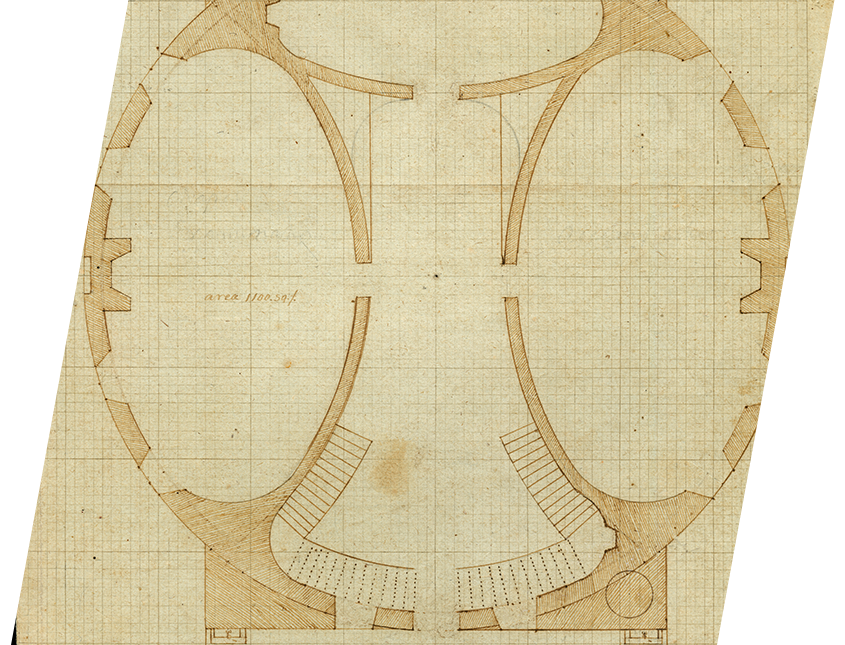

Part of Emmet’s chemistry classroom, the hearth eventually had been walled up and forgotten. Uncovered again during the ongoing, two-year renovation of the iconic building, it remains remarkably intact. Six feet wide, with four brick fireboxes and surfaces on which Emmet could work with chemicals, the hearth featured vents and flues that brought air in to feed the fires and draw off smoke and fumes.

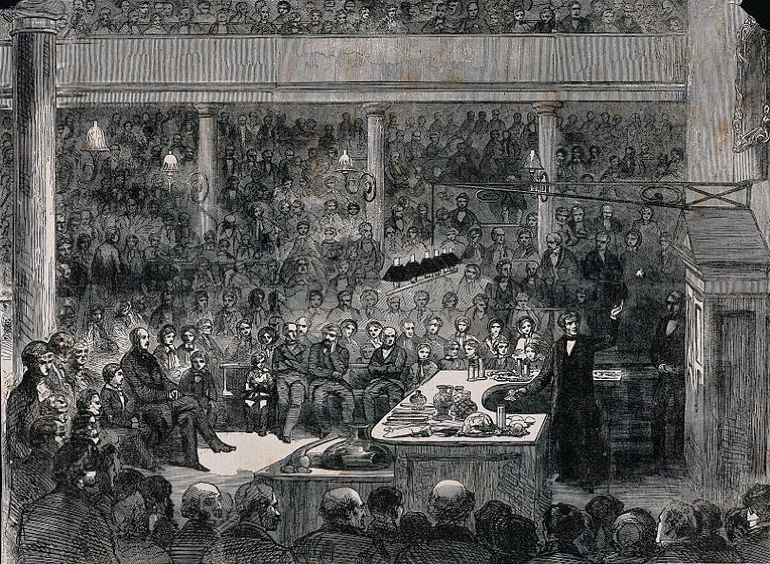

John Emmet helped improve chemistry education from featuring just lectures, as shown here, to a setting in which students conducted hands-on experiments.

Most of the hearth was discovered by accident this year when John G. Waite Associates project manager Matt Schiedt stuck his head through an opening in the Rotunda wall and looked up. “I was lying on my back looking up inside this little space,” he said. “I saw that there was a piece of cut stone, which is very unusual to have in this location. You could see that there was a square cut in the stone and that there was a finished space around that with plaster and painted walls.” Experts found remnants of experiments – part of a tapered glass tube, broken crucibles, homemade charcoal and small sheets of glass – items Emmet himself may have handled. Mark Kutney, an architectural conservator with University architect’s office, believes Emmet made some lab items as he needed them. “From some of the fragments we found, it appears they were melting glass tubing and making pipettes, and making small crucibles out of clay,” Kutney said. “In some of their experiments they would need to expose materials to high heat and observe the reaction.”

The room includes four furnaces – two near the floor and two higher up, a few inches below the working surface. Charcoal lay isolated on one of the high metal grates. “We know from the Proctor’s journal they delivered charcoal to Emmet in the Rotunda,”Kutney said. Emmet probably built a fire inside the center chamber, Kutney said, using the bellows tube to create hot coals. The charcoal would then be moved to the furnaces in the chemical laboratory in the amount needed for experiments. Records show Emmet’s interests were wide-ranging, inside the classroom and out, befitting a professor who taught the range of science as it existed in the 19th century. He experimented on silver and gold, researched batteries and how to make paint. He raised silkworms and succeeded in making a high-quality sewing silk and developed ways of dying and coloring the strands. He also shared Jefferson’s fascination with wine and experimented with European grapevines grafted onto native stock. In the mid-1830s, he was producing small quantities of wine and brandy.

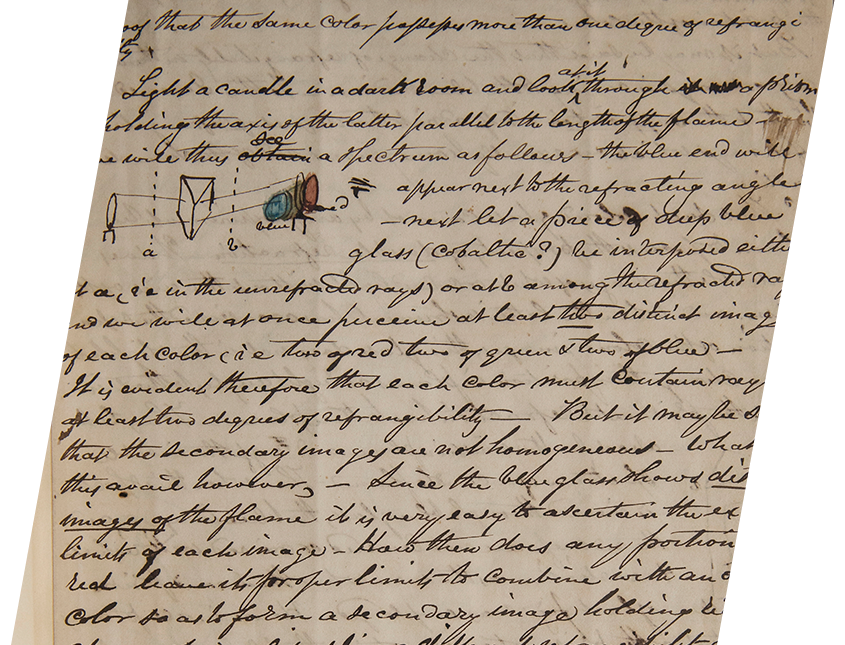

Emmet and his wife, Mary, lived initially in Pavilion I, where he kept a collection of reptiles and other local creatures. A brown bear he raised from a cub is said to have roamed at will through the house and garden. Emmet constantly exposed himself to chemicals. In 1830 one of his most serious injuries occurred when an assistant failed to recork a large bottle of sulfuric acid, which then spilled on Emmet’s shoulders and the assistant’s hands. Reacting to the pain, the assistant threw the bottle and it shattered on Emmet. His face was spared, but Emmet suffered from severe burns for months. Emmet bequeathed his hand-written notes and drawings to future generations – pages and pages outlining his chemistry syllabus, observations on experiments and natural phenomenon, and pieces of equipment archived in the University’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. “We have, in Emmet’s own hand, drawings of things that he ordered to use here, beakers and other devices,” Hogg said. Among them: a portable furnace, for which he paid $20; a copper boiler and chafing dish, with a thermometer, which cost $12.50; scales and weights for $16; a pneumatic trough lined with lead for $20. The total for the equipment he purchased in New York and brought to the University was $275.

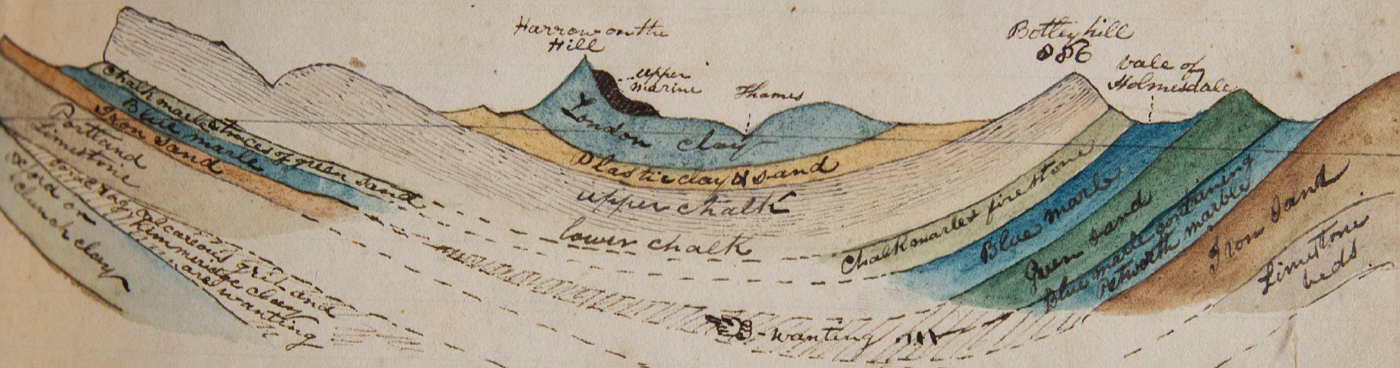

His notes also contain details of experiments, such as his work with crude batteries, and exacting illustrations of the various layers of rock and soil in geological formations. “There are meticulous drawings of geology, animals, pieces of equipment,” Kutney said. “This was, and still is, part of sciences. Since this was before photography, drawing was an essential part of recording observations.” Emmet’s mind produced a flurry of ideas, and his colleagues recognized in him an ability to function ahead of the day’s scientific curve. “I always thought there was a great probability that he would eventually light in on some discovery by which he would gain the renown due to his genius and zeal,” wrote Dr. George Tucker, the first professor of moral philosophy at the University, in a memoir, “Life and Character of Dr. Emmet,” which he presented to the Board of Visitors in 1845. “On several occasions, when discoveries in physical science have for their ingenuity or utility made a noise in the world, I would remember that Dr. Emmet had long before shadowed them out as practicable.” Emmet’s chemical hearth will be preserved as part of a display at the Rotunda.

Clues to the Past

Among many purposes, the current renovations to the University of Virginia’s Rotunda, the centerpiece of Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village, are intended to make the building more functional for educational uses. Already, the work is offering its own lessons about the building’s history.