BALTIMORE – The paper signs planted in the squares of Mount Vernon Place promoted upcoming African drum performances, a jazz trio and Saturday morning yoga. But as University of Virginia fourth-year student Chiquitta Branch and her 13 classmates continued their walking tour of Baltimore, they left behind the manicured public squares of the historic district.

A ramp for Interstate 83 and a series of concrete barriers and chain-link fences signaled an abrupt transition to West Baltimore as University Professor K. Ian Grandison and Professor of English Marlon B. Ross escorted their students. On the other side of the I-83 ramp, they walked past the intake center for the Baltimore city jail, a string of bail-bond offices topped with razor wire and a small cinderblock church. It was precisely the juxtaposition in urban landscapes that Grandison and Ross wanted to present to the students of their undergraduate seminars, “Landscapes of Black Education” and “Race, Space and Culture.”

“It’s amazing, just to have such a dividing line. It’s such a difference,” Grandison said.

UVA students visit a courtyard mural adjacent to The Avenue Bakery on Pennsylvania Avenue in West Baltimore, an area once known as the "Harlem of the South.”

Landscapes as Laboratories

In their collaborations since they both arrived at UVA in 2001, Ross and Grandison have sought to stretch the bounds of their particular disciplines. The overnight field trip to Baltimore served as a culmination of Ross and Grandison’s students’ work in critical landscape studies and was grounded in Grandison’s research in the article, “The Other Side of the ‘Free’way: Planning for Separate But Equal in the Wake of Massive Resistance,” recently published in “Race and Real Estate,” published last year by Oxford University Press.

“I was thinking, because of my involvement in the humanities, ‘How can I think about my discipline in relation to the humanities?,’” said Grandison, a landscape architect. “And this is what we came up with, this sort of blending of critical race studies in the humanities with landscape architecture, planning, architecture techniques and theories. What we came up with, in some ways, relates to race, spaces and cultural negotiation.”

The two professors have been leading similar class trips to Richmond and Washington for more than a decade in their interdisciplinary critical landscape courses. November marked the first trip to Baltimore, and it came months after the city had erupted in protests and violent disturbances prompted by the death of Freddie Gray in police custody last April.

The UVA College Council, a student-led organization, provided funds to support November’s trip, which included participation in a Morgan State University symposium on the architecture of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. Dianne Swann-Wright, a UVA alumna and former director of the Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park and Museum, also lent her efforts, along with Thomas Saunders of Renaissance Productions and Tours.

“From the moment that we mentioned we would be going to Baltimore, our students were excited and eager. Baltimore was still very much in the news at the time,” Ross said.

Branch, a fourth-year student from Richmond double-majoring in government and African-American studies, said the trip to Baltimore made everything they discussed in class “more real.”

“It’s one thing to talk about theory, but then practicing it or experiencing it is completely different,” she said. “The Baltimore trip sort of functioned like a lab where you put the theories that you’ve been learning in class to use.”

Historical readings and walking tours of Monticello, the central Grounds of UVA and downtown Charlottesville are incorporated within Ross and Grandison’s seminars, as well as reviews of demographic maps and the public policies fueling gentrification efforts that contribute to the segregation of black and white populations.

Fourth-year student Becca Pearson said that visiting Baltimore in the wake of last year’s tumult provided them an opportunity to understand how race shapes the built environment of a city.

“Traveling to Baltimore gave us a chance to see on a much larger scale how the construction of these structural landscapes creates both physical and social divides,” Pearson said.

Walking Across Dividing Lines

The first day of the Baltimore trip began with a visit to the Fell’s Point neighborhood, where abolitionist and social reformer Frederick Douglass grew up as a slave. At the Morgan State symposium, students listened to Grandison deliver the keynote lecture, entitled “The HBCU as Archive.”

The second day, Grandison and Ross led their students on a tour of Baltimore. It started with a visit to the Mount Vernon Place statue of Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney, a staunch supporter of slavery and the author of the 1857 Dred Scott decision ruling that no black, free or slave, could claim U.S. citizenship and thus they were ineligible to petition for their freedom. The students discussed the prominent Taney monument in light of a mayoral commission convened to determine what to do about the city’s Confederate monuments, comparing it to the oversized bust of Douglass installed at ground level in Fell’s Point’s Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park.

After crossing the city’s dividing line of Interstate 83 into West Baltimore’s predominantly black neighborhoods, Ross and Grandison’s classes visited St. Frances Academy. Founded in 1828 by the world’s first African-American order of nuns, the school provided education to free people of color and most likely, to enslaved children legally prohibited at the time from going to school. Stopping at Orchard Street Church, founded in 1825 by a former slave, the students stepped carefully down a narrow staircase to take cellphone pictures of a tunnel entrance to the Underground Railroad used by escaped slaves in the 19th century.

They passed blocks of boarded-up buildings before stopping again on the Old West Baltimore corridor, known as “the Avenue” during the Jim Crow era when it served as the celebrated Main Street of Baltimore’s black community. During a stop at The Avenue Bakery, Ross and Grandison’s students learned about grassroots efforts to revive the neighborhood.

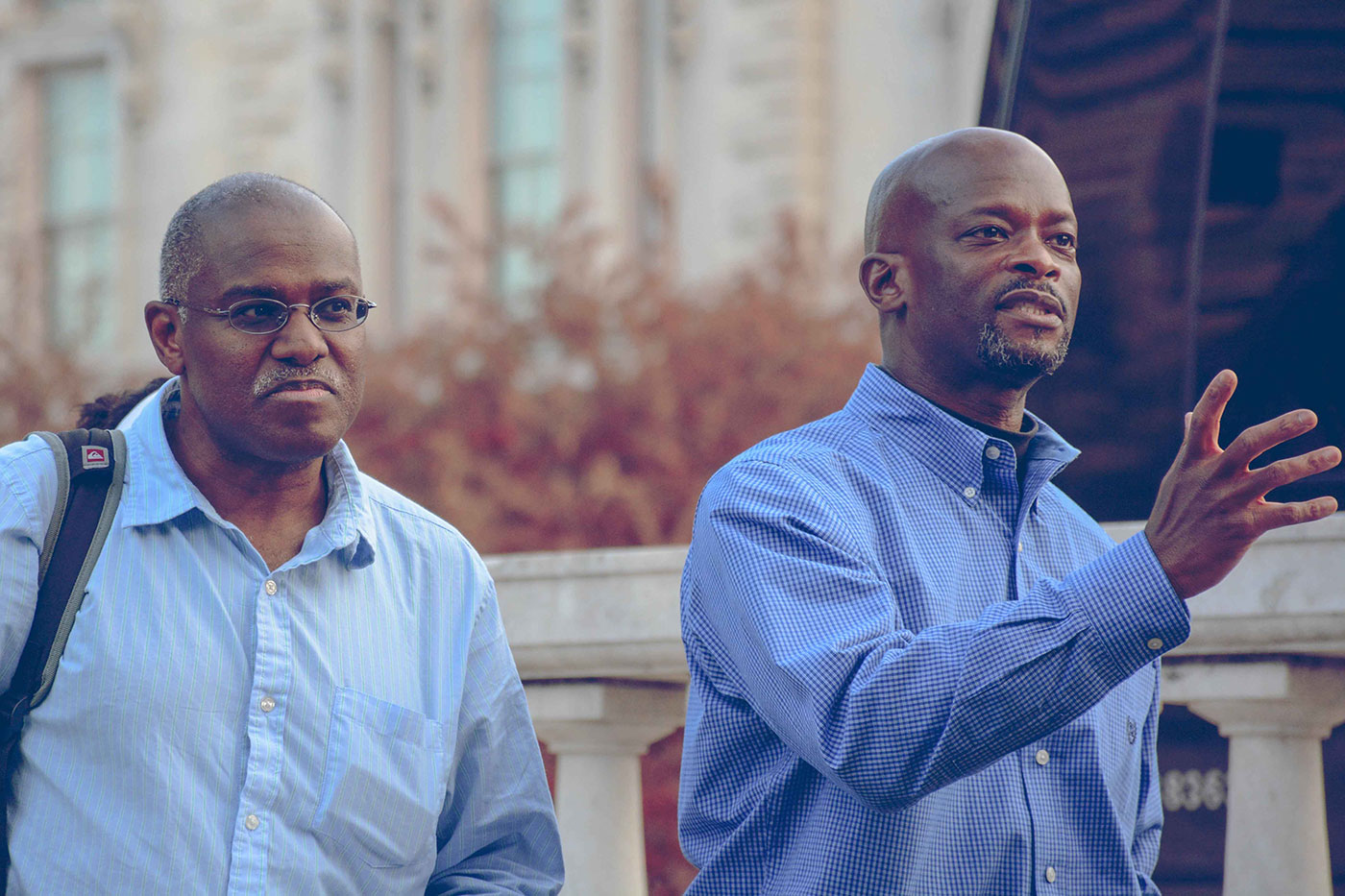

Ross, Grandison and their students pause at the access ramp to Interstate 83 that serves as a de facto dividing line in Baltimore.

Just a block or two from the bakery, the charter bus pulled over one final time to let the students step out near the site commemorating Freddie Gray, the 25-year-old Baltimore man whose death while in police custody sparked protests and riots in April 2015. Ross and Grandison wanted their classes to visit Gray’s neighborhood and the memorial to help their students understand the impact of racial barriers such as I-83 not only on the physical landscapes, but also on the everyday lives of those who reside on the “other” side of those divides.

Fourth-year UVA student Jackson Realo and his classmates stood quietly at dusk as they read the mural’s inscription:

The Power of the People

Rest in Peace

Freddie “Pepper” Gray

Realo grew up in Baltimore, but he said he went to a private all-boys school before college and was largely unaware of the history of the city’s black community before taking Grandison’s course.

“At first I was kind of hesitant to delve into it, but Professor Grandison is so enthusiastic and passionate that he really engages you,” Realo said. “I thought I knew those places before, but I didn’t have any context.”

Media Contact

Article Information

April 11, 2016

/content/baltimore-students-experience-racial-juxtapositions