The Declaration of Independence is near and dear to the University of Virginia. Literally.

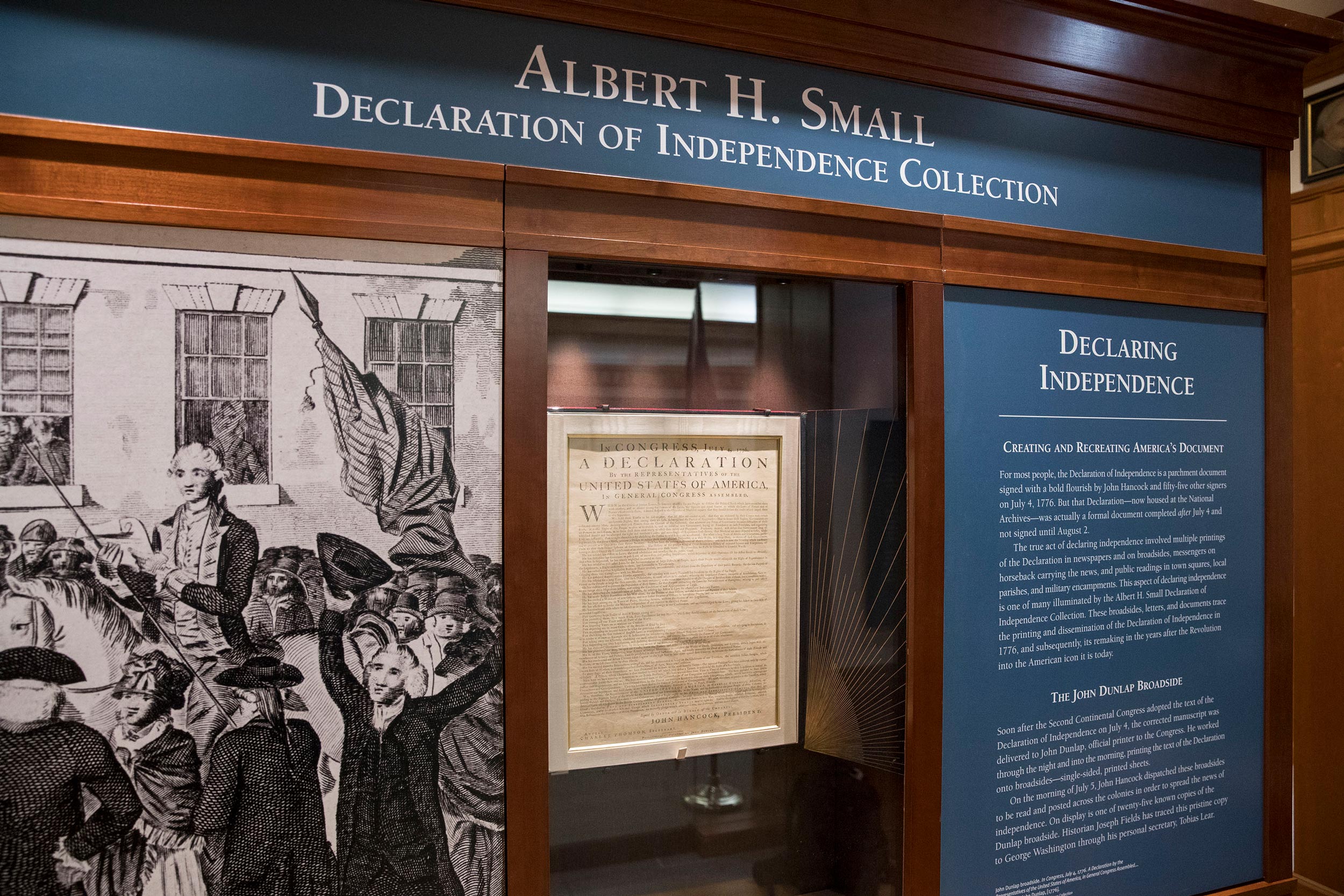

The University owns two copies of a rare early printing of the declaration, and “Declaring Independence: Creating and Recreating America’s Document” is a permanent exhibit on display in the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

Albert H. Small, a native of Washington, D.C., graduated from the School of Engineering and Applied Science in 1946. He began collecting rare books and manuscripts, and presented his extraordinary Declaration of Independence collection to the University beginning in 1999.

In observance of the holiday, brush up on 10 things you may not have known about the document.

1. The Declaration of Independence was not actually signed on July 4, 1776.

The Second Continental Congress adopted it that day, but the 56 representatives did not take up the quill pen until Aug. 2 – nearly a month later.

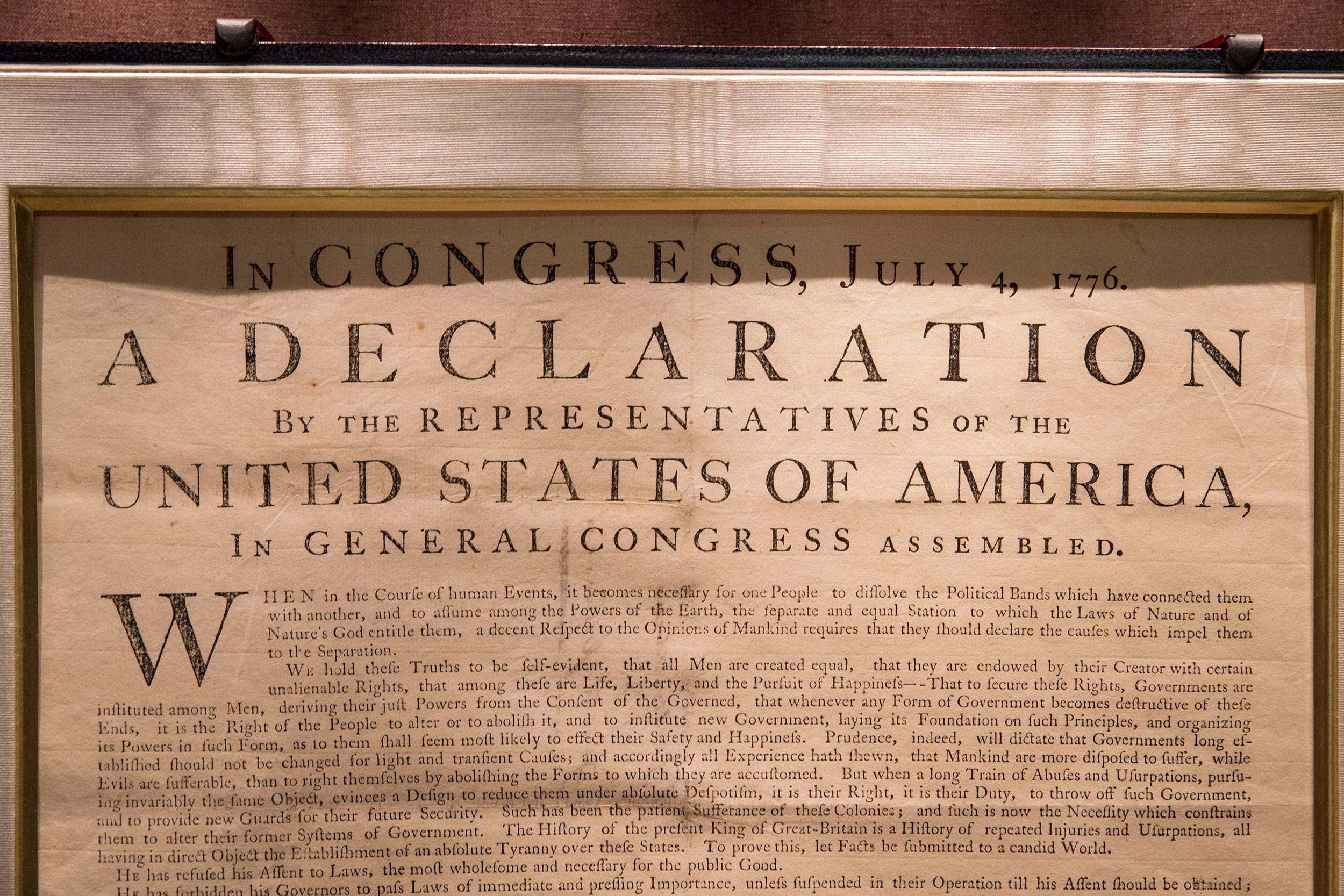

John Dunlap, the official printer of Congress, worked all night and into the morning of July 5 to produce the “broadside,” a large, single-sided sheet, similar to a poster. UVA's permanent exhibit includes one of only 26 known surviving copies of that first printing – just without all those signatures affixed at the bottom.

2. The only names that appear on that first copy are those of John Hancock, Congress’ president, and secretary Charles Thomson.

On display in the “Declaring Independence” exhibit are rare, early printings, as well as the subscription book in which Benjamin Owen Tyler took orders for his facsimile. His subscription book contains the signatures of Jefferson, James Madison, John Quincy Adams and other notables of the new republic.

3. The library’s copy was likely stolen from George Washington.

“There is a strong possibility that the Albert Small copy of the Dunlap broadside, now at UVA, once belonged to George Washington,” said David R. Whitesell, curator of special collections. “Its provenance can be traced back to the early 19th century, when it was in Tobias Lear’s possession. Lear, who was Washington’s personal secretary late in life, is known to have taken a number of documents, possibly including this broadside, from Washington’s papers shortly after Washington’s death in 1799.”

The library also owns an additional copy that it purchased in the 1950s. It is in poorer condition and only made available to qualified researchers.

4. The Pennsylvania Evening Post featured the declaration in its July 6 edition, the first to print it after the Dunlap broadside.

On July 5, Hancock had the broadsides distributed to be read and posted. Additional printings quickly multiplied throughout the colonies to spread the news of independence. The collection includes a copy of the Philadelphia newspaper, as well as newspaper reports from other colonies.

5. Thomas Jefferson was just 33 years old when he wrote the declaration, but already a well-known and accomplished writer. He received help from John Adams and Benjamin Franklin to draft the revolutionary document he called “an expression of the American mind.”

Jefferson left explicit instructions that he wanted his gravestone to be inscribed, “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom and Father of the University of Virginia.”

6. The New York delegation at first abstained from adopting the declaration at the July 4 meeting.

“The New York delegates to the Continental Congress abstained from adopting the declaration,” Whitesell said, “because they were awaiting instructions from the New York Provincial Congress. Those instructions (to vote for independence) did not arrive until after July 4, because the New York Provincial Congress had to evacuate New York on June 30 as British military forces approached.”

7. Ralph Trembly’s lithograph of the Founding Fathers signing the declaration depicts a fictional event.

The lithograph reproduced a painting by John Trumbull, which today hangs in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. The U.S. Congress commissioned Trumbull in 1817 to make the painting – even though it does not include all of the signers – together on July 4.

8. The signers knew what they were doing might cost them their lives.

Benjamin Rush, representative of Pennsylvania, wrote their action “was believed by many at the time to be our own death warrants.” The British did target the Founding Fathers, destroying and looting many of their homes. There’s a story that John Hart of New Jersey, when he came out of hiding and returned home, never found all of his children.

9. The Marquis de Lafayette hung an official engraving of the U.S. Declaration of Independence in his bedroom suite.

Secretary of State John Quincy Adams commissioned William J. Stone to make an official facsimile of the declaration in 1823, and 200 copies were printed, two of which the State Department gave to Lafayette.

10. The Albert Small collection is the most comprehensive collection of letters, documents and early printings relating to the declaration and its signers.

The exhibit also includes printings of the declaration through history, letters and documents from the 56 signers, and a 13-minute documentary film showing the story of the events that led to the founding of this country.

For those far from Charlottesville, you can visit the library's online exhibition that reveals the stories behind the production and dissemination of the Declaration of Independence.

Media Contact

Article Information

July 2, 2019

/content/did-you-know-10-facts-about-declaration-independence-0