As they walk among the rows of shelves in the University of Virginia’s Alderman Library, patrons don’t know they’re passing invisible clues that tell of prominent local families, U.Va. professors, students and donors – and the social importance of reading.

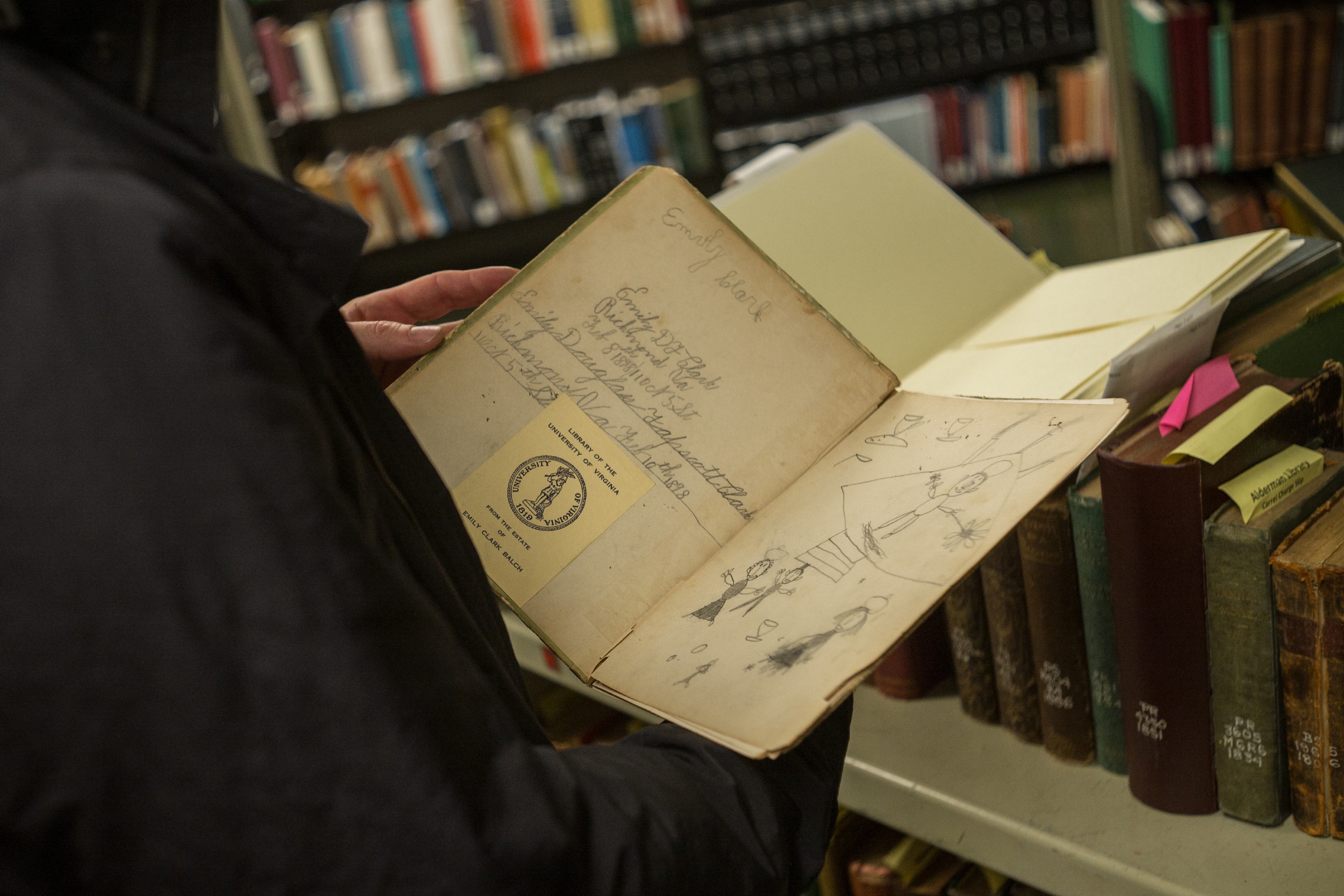

Upon and between their printed pages, the books on those shelves may contain well-known or historical signatures, drawings, pressed flowers, coin rubbings and other memorabilia. They might not have been checked out for a long time, because of their age or condition, yet each is unique.

Associate Professor of English Andrew Stauffer began a crowd-sourced project, “Book Traces,” earlier this year to preserve this hidden literary life of the 19th century before many older volumes get moved off of library shelves. He considers the project an “intervention” to retrieve these fragile copies that reveal aspects of social life, the history of reading and uses of the book.

Now Stauffer has teamed with Kara McClurken, head of the University Library’s preservation services, to expand the recovery effort. The Council on Library and Information Resources recently awarded them a two-year, $221,000 grant for their project, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” to discover, describe and preserve unique pre-1923 books in the circulating collection.

After the 1895 Rotunda fire destroyed U.Va.’s library, many people donated their own books to rebuild the collection, McClurken said.

Like many readers, “I used to think that things written in books were nothing but a defacement,” she said.

Then McClurken met Stauffer this summer in a Rare Book School class in the library. Through their conversations, she began to understand there were important things to be learned from the marginalia and artifacts found on the pages. The historical evidence “has a role to play” in scholarly research, she said.

With the grant, library staff members will seek to identify subject areas that are most likely to have marginalia. They’ll work on a process to record the information and enter it into the online catalogue; at U.Va., that’s Virgo. Because many of the volumes are fragile, they’ll figure out how best to preserve them. Another goal is to make sure other academic libraries can use the process.

“We want to figure out a work flow to get this information quickly and streamline the process,” said Stauffer, who has found, with the help of U.Va. students and people at other libraries, about 320 uniquely decorated books. One had handmade paper dolls and clothes tucked into its pages; in another, a Civil War soldier had drawn maps and troop formations.

McClurken said, “We estimate that there are 180,000 pre-1923 items in the Alderman collections, excluding periodicals.” Based on previous sampling, they estimate that 5 to 10 percent of them have evidence worth recording and hope to capture cataloguing information for about 12,000 books.

“Attending to our own legacy print collections is a priority at U.Va.,” U.Va. President Teresa A. Sullivan wrote in endorsing the project. “A Hidden Collections grant from CLIR would not only enhance the cataloging process of our own holdings in this area, but it would also help us to create a model for other libraries that house similar collections.”

Supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the council’s grant program, “Cataloging Hidden Special Collections and Archives,” selected 19 proposals from more than 90 submissions. The Council on Library and Information Resources is an independent, nonprofit organization that forges strategies to enhance research, teaching and learning environments in collaboration with libraries, cultural institutions and communities of higher learning.

Stauffer is excited about the project: “Once we have a methodical process, I think we’ll be amazed at what we find,” he said.

Media Contact

Article Information

December 16, 2014

/content/grant-boosts-efforts-catalog-secrets-hidden-old-library-books