History professor Andrew Kahrl tracks racial discrimination through the tax assessor’s office.

Kahrl, an associate professor and joint apointee in the University of Virginia’s Corcoran Department of History and the Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies, specializes in African-American history and teaches about segregation and discrimination in housing and real estate. He has published one book, “The Land Was Ours: How Black Beaches Became White Wealth in the Coastal South,” has completed another on desegregating Connecticut beaches, and is researching a third on how tax liens and tax sales became a tool used by predatory land speculators to acquire black-owned land.

“My interest has always been in making boring topics interesting,” Kahrl said. “I think some of the best history writing is that which takes these issues that, on the surface, seem to be mind-numbingly boring – such as tax assessments. But you need to look at what the consequences are, of the impact on communities trying to become stable and build up wealth.”

Kahrl’s research explores the use of municipal power to discriminate, limit development and restrict people to certain geographic areas. Kahrl started out researching the effect of segregated recreation facilities in the South, where blacks were excluded from white resorts, beaches and swimming pools and where black entrepreneurs, in response, developed their own properties and facilities. His research spanned from the 1890s through the 1960s, with most of his focus on the period from 1920s through the 1960s.

Visitors to Gulfside Assembly, an African-American religious resort in Waveland, Mississippi, bathing in the Gulf of Mexico in the 1920s. (Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

“You have, on the one hand, a growing demand amongst African-Americans in the South for summertime leisure activities and leisure spaces where they can go without fear of harassment or assault,” he said. “And then on the other hand, you have African-American landowners who are well-situated to provide those services. So you see waterfront landings being converted into seasonal enterprises. You see these commercial enterprises take shape that are black-owned and for a black consumer audience.

“When I began studying the history of beach segregation and the formation of separate black leisure spaces in the Jim Crow era, I was mainly interested in learning what took place in these spaces – the sights, the sounds, the music, the cultural dimensions of leisure,” he said. “But I quickly learned that space itself – and the land, in particular – formed a critical part of the story, and that in order to understand how these places came into being and how they fell apart, you need to understand the history of its ownership and commercial development.”

He had assumed that as blacks integrated white recreation areas, the black recreation facilities died because blacks stopped going to them.

“As I quickly learned, however, the demise of these places – and blacks’ ownership stake in coastal property – was anything but inevitable,” he said. “Many of these places were legally stolen from black people by private investors working in concert with local officials.

“From this revelation, I came to see the entire history of these places differently, and gravitated away from the cultural dimensions of black leisure to the economic and environmental issues surrounding coastal real estate and development in the 20th century.”

After integration, many of the owners fell prey to predatory land speculators who often acquired the valuable beachfront property through subterfuge. Local officials played a role through the power to tax and assess. Kahrl found examples of local officials who assessed black property owners at highly inflated rates in an effort to tax them off the land. Sometimes the overassessments were subtle; other times they were flagrant.

“This practice was pervasive,” Kahrl said. “It was something that was taking place throughout the South and it is clear that it is discriminatory in nature. African-Americans were consistently taxed higher on their property than white homeowners and landowners in the same neighborhood.”

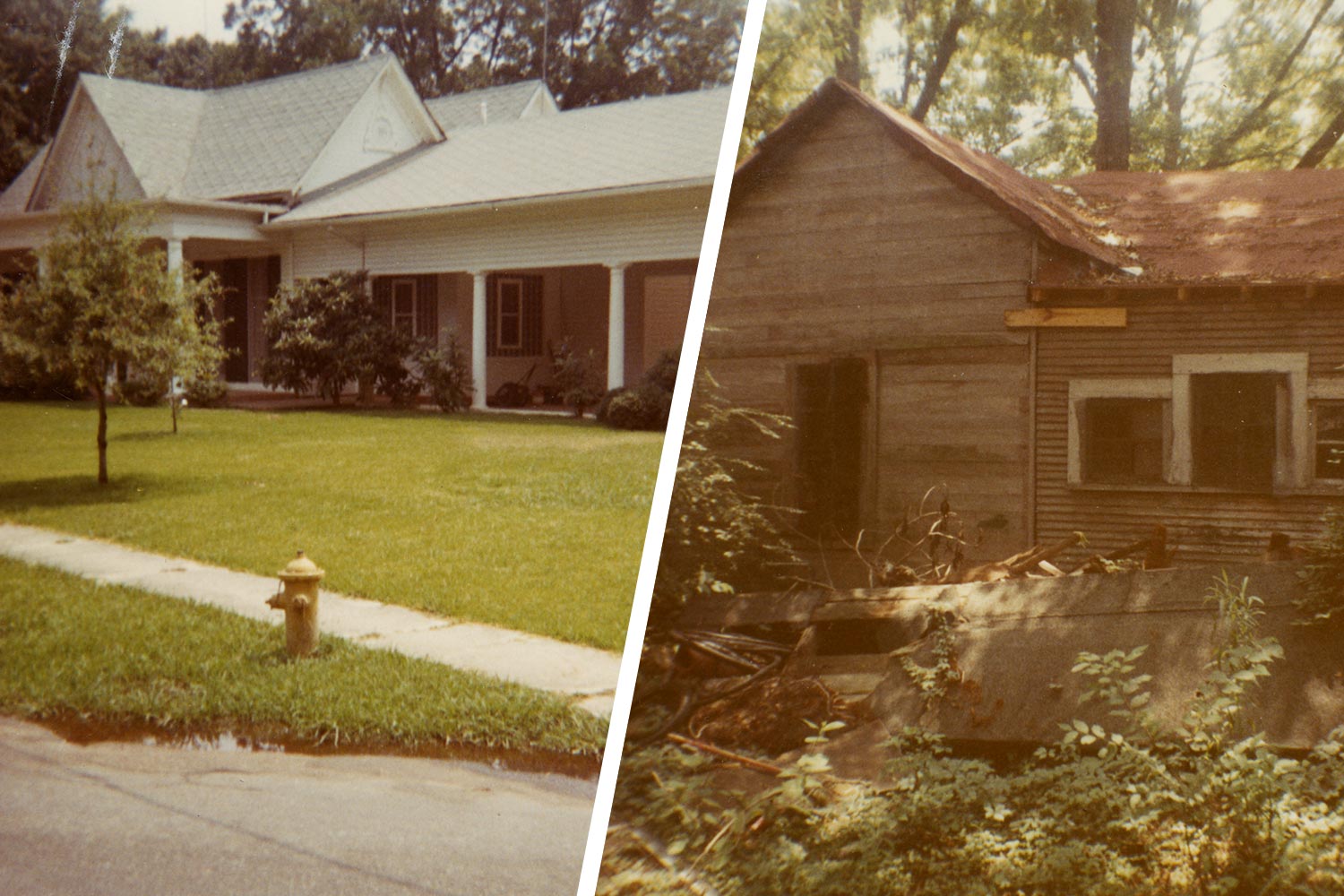

The homes of white Edwards, Mississippi, resident Zeith Tupperfield, left, and black Edwards resident Sam Jordan, right, were both assessed at $1,000 on the town’s 1967 land assessment roll. (Mississippi Department of Archives and History, Jackson)

In some states, if the black landowners missed a tax payment, a lien would be put on the property – and the lien or the property would eventually be sold at a tax sale, where speculators could purchase the debt, add legal fees to it and eventually seize the property for much less than for what it would have sold in an arm’s-length transaction.

“The real tragedy of the story is that the land today is worth millions and millions of dollars, some of the priciest real estate in America,” he said. “A lot of that was owned by African-Americans just a couple of generations ago. They lost most of that land and got very little in return.”

Kahrl said the more he dug into land records, the more he found that such practices were not limited to the South. In Chicago, New York, Philadelphia and other Northern cities, black-owned properties also were taxed at a higher rate – and had little to show for it.

“African-American schools are getting less support. Black neighborhoods are getting less in public services,” he said. “I think it is a very important issue that has not gotten the type of attention it deserves, and it really challenges some of our assumptions about taxes and race in America.”

In the early 20th century, Virginia maintained separate tax rolls for black and white property owners, which Kahrl said made discrimination – and, decades later, historical research – easier.

Kahrl was raised in the Midwest, the son of a history professor at Ohio State University at Mansfield. His father, wary of the academic job market, discouraged him from graduate school, but Kahrl persisted.

“You really need to do work that is important – work that asks new questions about familiar topics or introduces fellow historians and the general public to topics that were not even on their radar – work that is relevant to questions that are shaping society today,” Kahrl said.

Andrew Kahrl’s father, also a history professor, advised against an academic career, but Kahrl saw it as his opportunity to make the world a better place. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Kahrl has focused on black history because he feels it is core to understanding the country as it stands today.

“As a middle-class white kid growing up in a virtually all-white Midwestern town, I saw firsthand the corrosive effects of white privilege on American society,” Kahrl said. “I knew that I had the choice to ignore the oppression and exploitation suffered by black Americans, to look the other way and pretend, like the vast majority of the people I grew up with did, that it was someone else’s problem.”

But Kahrl thought he was in a position to do something about the inequality he saw.

“Growing up in this environment, I came to realize that the complacency and indifference to the problem of race found in places like my hometown constituted a significant – perhaps the most significant – obstacle to a more just and equal society,” Kahrl said.

His next book, scheduled to come out in the spring, centers on Ned Coll, a white activist in Connecticut who led a movement in the 1970s to open the beaches to all races, a battle carried out on the shore and in the courts.

“I use this struggle as a window onto race and inequality in modern America,” Kahrl said. “Connecticut is actually a very unequal state. We associate it with liberalism and it is a quintessential blue state today, but it is also a state that has profound inequality. And by some metrics it is the most unequal state in American when you look at the divide between the wealthy and the poor. There are a lot of pockets of extreme wealth in Connecticut versus the poor, as seen in cities such as Bridgeport and Hartford.”

Coll started a Hartford-based, anti-poverty program and became aware of the restricted beaches when he was trying to arrange day trips for the children in the program. The municipalities did not restrict their beaches based on race, but simply restricted outsiders.

“It becomes a real battle among communities that do not see themselves as racist and profess up and down that their access policies are not motivated by racism,” Kahrl said. “They have an idea of local control, but Ned Coll is pointing out that their actions have consequences, very negative consequences on particular groups in society. It is very much elitism. But elitism often has racially disproportionate affects and this is the case here.”

Kahrl, who has been teaching at UVA since 2015, offers a class in “From Redlined to Subprime: Race and Real Estate in the U.S.,” which examines discrimination in housing markets. He said students are eager for the information.

“I have been blown away by the energy and the enthusiasm, the sort of engagement of ideas among the students I have had take my classes,” he said. “I think historians especially have to have a sense of perspective here as to what have been the lived experiences of students.”

Kahrl wants his students to do more than passively digest history. An upcoming class called “All Politics Is Local” focuses on municipal governments, such as city and school districts, to the point of having students attend local government meetings to better understand their workings.

“The decisions made by planning boards and zoning boards are hugely consequential and it is frightening that no one is paying attention to these things,” Kahrl said. “It is a matter of holding local power accountable, something I take very seriously in my teaching.”

He said the students need to understand the more subtle forms of governmental abuse and the consequences to communities and to individuals.

“We all know about the Jim Crow drinking fountains, the segregated schools and the explicit forms of racial discrimination,” Kahrl said. “They were taking place consciously and maliciously. But we know very little about exclusionary zoning, in which race is nowhere in the law and yet the practical consequences of it is something that was prevalent in the Gold Coast of Connecticut: ‘We’re open to anyone. We don’t discriminate.’ And yet they would have laws on the books that would say that you couldn’t build a house on less than a three-acre lot. That ensures that only wealthy people live in your community. Or laws that you can’t have multi-unit dwellings, so there are no apartments. All these things basically have the same effect in segregating communities.”

Kahrl understands that students, and readers, do not warm to discourses on tax liens and assessment schemes, so he focuses on the human dimensions of their consequences. He recognizes the human drama that occurs in planning and zoning boards and in tax assessors’ offices.

“Historians’ unique contribution is storytelling,” he said. “That is what we are in the truest sense, being able to tell stories of our past, that help us better understand where we are today as well.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 26, 2017

/content/historian-plumbs-tax-records-patterns-racial-discrimination