From “a city upon a hill” to “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” Americans have used the religious idea of the apocalypse to envision a glorious future or the end of the world, and to explain their history, as well as the unexplainable in everyday life.

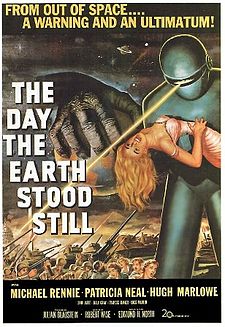

A University of Virginia January Term class, “American Apocalypses,” is combining religion, history, politics and popular culture – especially as depicted in science fiction and disaster films from the 1950s to the present – to explore the various elements of what instructor Matthew Hedstrom called an American obsession with the end: rapture theology, asteroids, environmental catastrophes, alien invasions, nuclear winters, zombies and technological mayhem.

“End-time scenarios – whether of ultimate destruction or eternal bliss – help us make sense of unspoken hopes and unspeakable fears, express outrage, mobilize movements for change and relate our individual lives to a larger order,” said Hedstrom, an assistant professor of religious studies and American studies in the College of Arts & Sciences.

J-Term courses, as they are called, are intensive two-week seminars that encourage extensive student-faculty contact and allow students and faculty to immerse themselves in a subject.

Early in his course, Hedstrom and the 15 students taking the class talked about how John Winthrop, the early governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, called on the Puritans to fulfill the biblical covenant with God to create “a city upon a hill,” a shining example of a holy community. God would protect them and bestow his beneficence upon them, as long as they were good Christians and lived a proper religious life.

The divine mission eventually infused politics and culture in America. Historians refer to the notion as “American exceptionalism.” It became part of American political identity and the people’s part of the covenant redefined as creating a beacon of liberty, Hedstrom said.

America’s mission has all too often been enacted through violence and conquest, justified as fighting for its righteous cause of spreading liberty, he pointed out.

The Civil War and its scale of violence challenged the notion, however, that America and its people were on the right track and would be spared from suffering.

“The Civil War was critical for thinking about the apocalyptic idea that society must be going through a violent decline,” he said. The war was also thought to be a cleansing of America’s sins, especially the sin of slavery. In his second inaugural address, President Abraham Lincoln invoked the Lord’s judgment to explain the war, blending theology with secular politics, Hedstrom said.

For their first paper, the students explored the way religious millennialism – Christ’s second coming – and apocalypticism have often been harnessed to political and social movements. Hedstrom said he “was pleased to see students trying to understand the apocalyptic nature of American exceptionalism – a key concept in American studies that shows up powerfully in the readings on the Revolution and Civil War especially.”

The students also pursued secular ideas of the apocalypse in a future where technology assumes the characteristics of religion; it can be good or evil, can save people or destroy them. Some scientists, such as inventor Ray Kurzweil, envision that humans will be able to meld with computers and essentially live forever.

Others question technology or see it as leading to humanity’s downfall for a variety of reasons. The reality TV show, “Doomsday Preppers,” focuses on real people who are stockpiling food, medicine and weapons, preparing for some kind of apocalypse that’s vaguely described.

Movies such as “Blade Runner” and “Gattaca” extrapolate what might happen if certain technological developments, such as genetic engineering or intelligent robots, evolve to a certain extent.

Environmental catastrophe as a result of humankind’s pursuit of technology often plays a part in the scenario.

“We had a great conversation this morning about apocalypticism in the environmental movement,” Hedstrom said. “The students have been very open to the ideas presented in the class, especially about the relationship between religious and secular/technological forms of apocalyptic culture.”

He hopes the students learn to think of history and civics in a new way and to see how popular culture is related, he said.

Andrew Annex, a third-year environmental sciences major, said, “I wanted to take this class because we as college students take in a lot of media related to the apocalypse – ‘The Walking Dead’ [a television show about zombies and survivors], the ‘Fallout’ series of video games [which features a post-apocalyptic setting], films like ‘Dr. Strangelove’ [a satire of the nuclear age], etc. – and I wanted to approach this media and the concept of apocalypse and post-apocalypse from an academic perspective.”

When the film “The Day the Earth Stood Still” was released in 1951, the U.S. had bombed Japan at the end of World War II and the Cold War was just heating up. In the movie, a sophisticated alien, accompanied by a robot, visits Earth to warn humanity that it has become too violent and if humans don’t find peace, they’ll be destroyed.

As the class looks at some of the many ways Americans have envisioned the end of the world, they are considering what those visions have to say about them and the America we inhabit, Hedstrom said.

Media Contact

Article Information

January 9, 2013

/content/j-term-course-examines-why-americans-can-t-let-go-apocalyptic-predictions