U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who died Friday at age 93, left a lasting impact on American law – and also on the University of Virginia School of Law.

O’Connor, the first woman to serve on the high court, was a William Minor Lile Moot Court competition judge and recipient of the 1987 Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Law.

O’Connor served in the Arizona Senate and Arizona Court of Appeals before being nominated to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1981. She retired in 2006 to care for her ailing husband and was succeeded by Justice Samuel Alito.

Journalist and historian Evan Thomas, a 1977 graduate of the Law School, published the O’Connor biography “First” in 2019, drawing on exclusive interviews and first-time access to the justice’s archives.

“Justice O’Connor [for] her 25 years was the fifth vote, the decisive vote 330 times,” Thomas told PBS in an interview about the book. “It was Justice O’Connor who kept alive affirmative action for 25 years. It was Justice O’Connor who kept alive abortion rights for 25 years. She was a huge force on freedom of religion. She was the fifth vote in Bush v. Gore. She had enormous power, maybe more power than any American woman has ever had.”

O’Connor stands with Dean Richard Merrill and UVA President Robert M. O’Neil in the Rotunda. (Photo courtesy UVA Law Special Collections)

Two UVA Law alumni clerked for O’Connor: Gary L. Francione, a 1981 graduate who clerked during the 1982 term, and Stanley J. Panikowski, a 1999 graduate who clerked in the 2000 term. Today, Francione is a professor at Rutgers Law School and Panikowski is co-chair of appellate advocacy practice at DLA Piper.

As part of the interview process, Panikowski had lunch with O’Connor and her clerks, chowing down on three bowls of the justice’s homemade spicy bean chili, he told the Virginia Law Weekly in 1999.

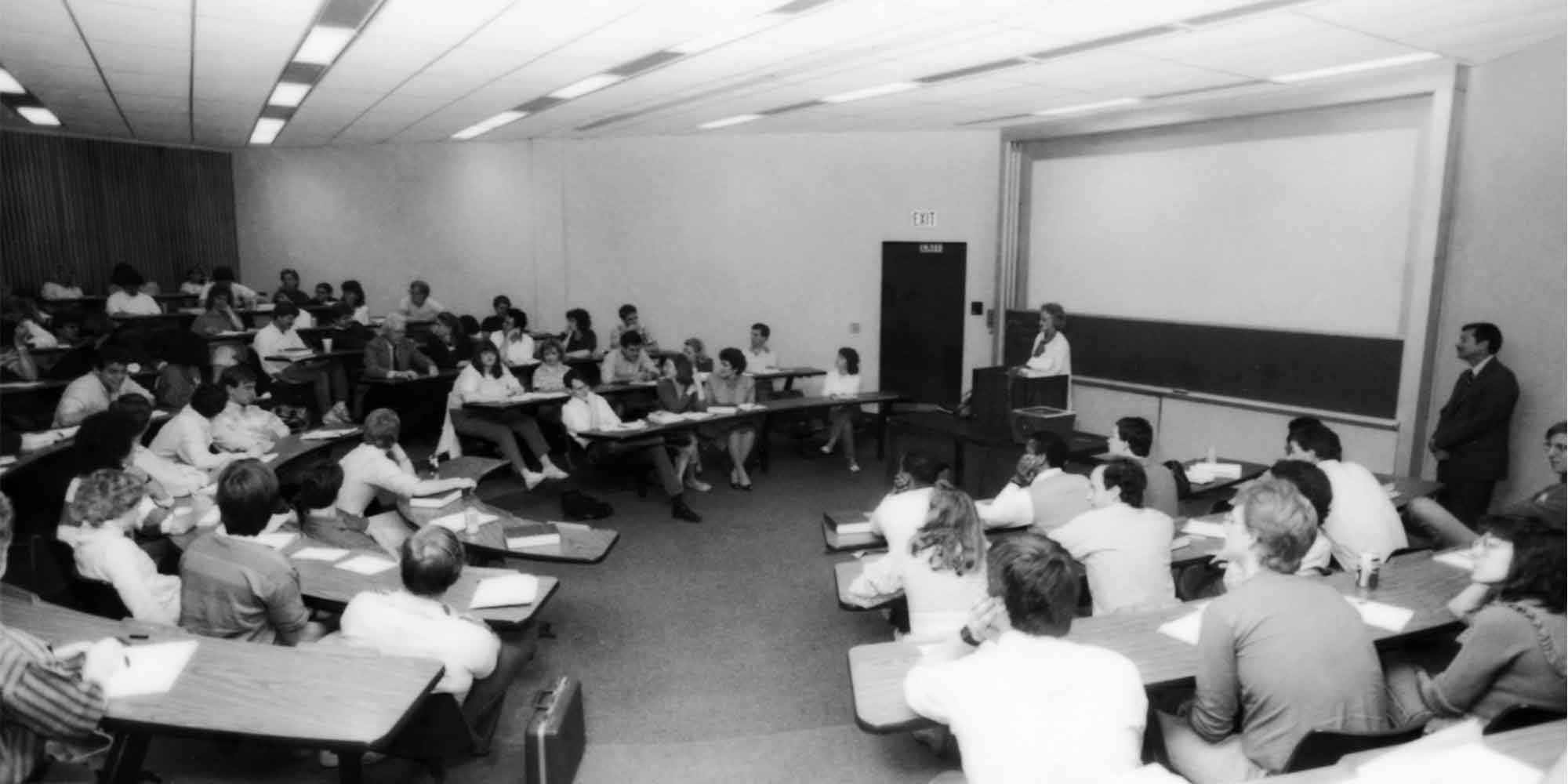

O’Connor visited the Law School a handful of times in the 1980s. In 1985, O’Connor was one of three judges to hear arguments in the moot court competition finals. D. Ruth Buck, then a third-year law student and now a UVA Law professor, was a finalist and won the award for best individual oral advocate.

“I would say it was more exciting than stressful,” Buck said, “figuring that I might not ever argue in front of a Supreme Court justice again.”

Buck recalled that O’Connor’s demeanor was more pleasant than confrontational. At a dinner after the event, O’Connor chatted with Buck’s moot court partner, Lynne Fleming, about balancing work and child care.

“I think she definitely set the tone for the bench,” Buck said. “A person can be incredibly incisive and confident and intelligent, and at the same time be gracious.”

UVA Law professor John Setear clerked for O’Connor for the 1985 term. He said the justice took a personal interest in her clerks by taking them out on cultural outings, asking about their children (she called them her “grandclerks”) and arranging dates for single clerks. Setear went to the theater on a double date with the O’Connors and whitewater rafted with the self-described cowgirl.

As for O’Connor’s work inside the marble walls, Setear said her newness to the court at the time of his arrival, and her lack of experience in federal cases, forced her to take a much more thorough and meticulous approach, a trait that rubbed off on her clerks.

“She was very conscientious,” he said. “She wanted to make sure you got everything right and that you chased down every legal concept or topic or line of cases that might be relevant.”

Setear attributed her swing-vote status to the court becoming more conservative with new appointees over time, but noted that her moderation mirrored her legal management style.

“I also think she was in the middle because she was a careful lawyer,” he said, “and she was a classic sort of common law judge in the sense that she looked at the case before her and the facts before her and she tried to resolve that case, and she was cautious about making sweeping pronouncements and going beyond that case.”

Setear said one key lesson he learned from working for O’Connor as a young lawyer was to listen and respect both sides of an argument, even when disagreeing.

“I always felt that she was listening to both sides,” he said. “Some people thought that she picked her clerks to get a variety of viewpoints in the chamber every year so that she would hear the different viewpoints.”

Although Setear said he thinks O’Connor will be remembered above all else as the first woman on the court, he said the appointment spoke to her intelligence, self-restraint and temperament.

“As I saw her in the middle of the 1980s, Justice O’Connor, as a justice and as a person of such accomplishment – a woman of such accomplishment – had an aura of perfection and invulnerability about her,” Setear wrote in his paper. “But as the years went by, and I heard that Justice O’Connor’s own parents had died, that she had breast cancer, or that she was stepping down from the bench for family reasons, I came to realize that this person of unearthly energy and confidence was nonetheless vulnerable, like all the rest of us, to the passage of time.”

Read law professor A.E. Dick Howard’s tribute to O’Connor.

Media Contact

Article Information

April 16, 2025