February 2, 2012 — Longtime University of Virginia biologist Oscar Lee Miller Jr., whose scientific discovery in the 1960s led to many important advances in DNA science and is still used in labs today, died Jan. 28. He was 86.

Miller joined the U.Va. faculty in 1973. During his tenure, he was chair of the Department of Biology in the College of Arts & Sciences and held William R. Kenan Jr. and Lewis and Clark professorships. Miller was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1978, one of the highest honors for a scientist or engineer.

Upon arriving at U.Va., "Oscar immediately set about creating an interactive environment in the department, believing that frequent informal social contact between gifted people would spark ideas and advance intellectual inquiry," recalled Reginald Garrett, professor and associate chair of biology and Miller's longtime friend and colleague.

"He was a very sociable person himself, with an aura of informality that was unexpected in a scientist of such accomplishment," Garrett said. "He drew the department together through parties at his home, serving what he called 'finger food' – items one could eat while standing. His tactic was to forge small conversational groups, with participants shifting from one circle to another, mixing and sharing impressions and ideas."

During Miller's time on Grounds, Garrett said, the biology department "became an incubator for administrative associates," many of whom went on to become leaders within the University's fiscal divisions.

"Oscar also relished his role as a mentor for students, and he inculcated into them many of his fine qualities," Garrett said.

Ann Beyer and Amy Bouton, who once worked in Miller's lab, are now professors in the University's School of Medicine. Another former graduate student, Steve McKnight, chairs the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Texas, Southwestern; co-founded a drug development company; and is a member of both the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine.

"Oscar's generosity and kindness were well known by those he supervised. He was scrupulous about his science, yet he always had time to nurture his junior colleagues," Garrett said. "Oscar was a man who exemplified his time – a farmer whose curiosity about nature sent him into the academic halls of science; a Southerner who never forgot his manners, his hospitality, or his good humor; and an investigator whose intuition, persistence and dexterity dispelled some of the vexing mysteries in the early days of molecular biology."

Beyer called Miller "a fantastic mentor and a very dear friend."

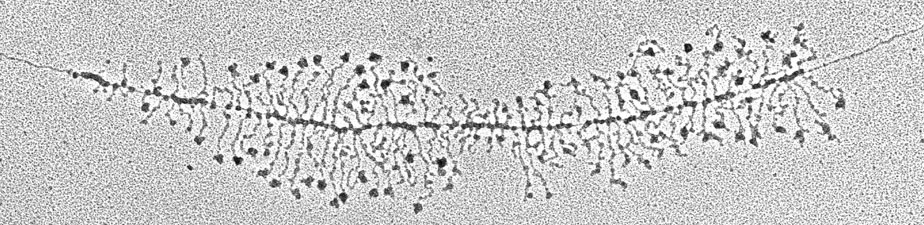

"He developed an extremely valuable scientific technique, appropriately called 'Miller Chromatin Spreading,' in which the cell's DNA is spread out to get a snapshot of individual active genes," she explained. "I strongly believe that this is one of the rare situations in which a technical breakthrough would never have been made if this particular person hadn't done it.

"Oscar did much of his thinking outside the box. With the goal of loosening the tightly packed DNA so as to reveal its workings, he tinkered for years, finally perfecting a procedure that no card-carrying biochemist would ever have considered, and that has never been altered or improved upon.

"The resulting electron micrographs of active genes, which were his vision from the beginning, are now in every biology textbook and have greatly enriched our understanding of genetic mechanisms," she said. "I am very proud to be one of several protégées who have built our careers on the method he developed for seeing genes in action."

Herbert Macgregor, professor emeritus of zoology at the University of Leicester (U.K.) and editor of the journal Chromosome Research, said he first met Miller in 1969, shortly after he had developed and published his spreading technique.

"I remember being utterly humbled and overawed by the extraordinary skill, ingenuity, inventiveness and courage behind the work," he said, noting that the artice in Science describing the technique has been cited nearly 1,000 times. "In terms of impact in the field of chromosome and nuclear science, it is almost unrivaled."

Miller told a University Journal reporter in 1996 that induction into the National Academy of Sciences was one of his greatest memories. "The proudest moment," Miller said, was when the academy's president called him "the virtuoso with the electron microscope."

"My wife was smiling, and I blew her a kiss from the stage," Miller recalled.

Miller's academic career led to a number of fellowships and visiting professorships. He was named a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1980. He was visiting professor of biology at the Center of Investigation and Advanced Studies in Mexico City, the California Institute of Technology, the Max Planck Institute for Cell Biology in Heidelberg, Germany, and the University of California, Irvine. He was the Senior Fulbright Scholar at the Division of Molecular Biology, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in New South Wales, Australia.

The esteem felt for Miller by students and colleagues culminated on Sept. 8, 1995, when Miller, then 70, was honored with a day-long symposium, which coincided with the closing of his lab. Called "Oscarfest," the program included a roast and a banquet, and was planned by his students-turned-colleagues, Beyer among them. Oscarfest featured five speakers – four scientists who were part of an international symposium that Miller helped organize in Uruguay some 30 years earlier, and a fifth who was Miller's first U.Va. graduate student.

"They were honoring me because there was nothing left for me to give them other than love," Miller said in the University Journal article.

Miller received the Lifetime Achievement Award in Science from the commonwealth of Virginia in 1997. He retired from U.Va. in 1998 as professor emeritus, but continued to teach his popular course, "Seeing Genes in Action," to first-year students and to advise undergraduates and link them with U.Va. medical researchers.

He told reporters in 1996 and 1997 that in his retirement years, he planned to travel with his wife, write poetry, learn to play the piano, compose "an amateurish sonata," and choose what he wanted read and played at his memorial service.

Miller was born April 12, 1925, in Gastonia, N.C. Prior to his academic career, he served in the U.S. Navy from 1943 through 1946. After earning bachelor's and master\'s degrees in agronomy from North Carolina State University, he was a farmer for six years, and then enrolled in the University of Minnesota, where he earned his Ph.D. in plant genetics. He joined the research staff at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 1961 and began the work that earned him worldwide renown as a molecular biologist.

He is survived by his wife of 63 years, Mary Rose Miller; his sister, Caroline Miller McClintock; his younger brother, the Rev. John Miller; his daughter, Sharon Miller Bushnell; his son, Oscar Lee Miller III; and three granddaughters.

His memorial service will likely be held in March.

Miller joined the U.Va. faculty in 1973. During his tenure, he was chair of the Department of Biology in the College of Arts & Sciences and held William R. Kenan Jr. and Lewis and Clark professorships. Miller was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1978, one of the highest honors for a scientist or engineer.

Upon arriving at U.Va., "Oscar immediately set about creating an interactive environment in the department, believing that frequent informal social contact between gifted people would spark ideas and advance intellectual inquiry," recalled Reginald Garrett, professor and associate chair of biology and Miller's longtime friend and colleague.

"He was a very sociable person himself, with an aura of informality that was unexpected in a scientist of such accomplishment," Garrett said. "He drew the department together through parties at his home, serving what he called 'finger food' – items one could eat while standing. His tactic was to forge small conversational groups, with participants shifting from one circle to another, mixing and sharing impressions and ideas."

During Miller's time on Grounds, Garrett said, the biology department "became an incubator for administrative associates," many of whom went on to become leaders within the University's fiscal divisions.

"Oscar also relished his role as a mentor for students, and he inculcated into them many of his fine qualities," Garrett said.

Ann Beyer and Amy Bouton, who once worked in Miller's lab, are now professors in the University's School of Medicine. Another former graduate student, Steve McKnight, chairs the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Texas, Southwestern; co-founded a drug development company; and is a member of both the National Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Medicine.

"Oscar's generosity and kindness were well known by those he supervised. He was scrupulous about his science, yet he always had time to nurture his junior colleagues," Garrett said. "Oscar was a man who exemplified his time – a farmer whose curiosity about nature sent him into the academic halls of science; a Southerner who never forgot his manners, his hospitality, or his good humor; and an investigator whose intuition, persistence and dexterity dispelled some of the vexing mysteries in the early days of molecular biology."

Beyer called Miller "a fantastic mentor and a very dear friend."

"He developed an extremely valuable scientific technique, appropriately called 'Miller Chromatin Spreading,' in which the cell's DNA is spread out to get a snapshot of individual active genes," she explained. "I strongly believe that this is one of the rare situations in which a technical breakthrough would never have been made if this particular person hadn't done it.

"Oscar did much of his thinking outside the box. With the goal of loosening the tightly packed DNA so as to reveal its workings, he tinkered for years, finally perfecting a procedure that no card-carrying biochemist would ever have considered, and that has never been altered or improved upon.

"The resulting electron micrographs of active genes, which were his vision from the beginning, are now in every biology textbook and have greatly enriched our understanding of genetic mechanisms," she said. "I am very proud to be one of several protégées who have built our careers on the method he developed for seeing genes in action."

Herbert Macgregor, professor emeritus of zoology at the University of Leicester (U.K.) and editor of the journal Chromosome Research, said he first met Miller in 1969, shortly after he had developed and published his spreading technique.

"I remember being utterly humbled and overawed by the extraordinary skill, ingenuity, inventiveness and courage behind the work," he said, noting that the artice in Science describing the technique has been cited nearly 1,000 times. "In terms of impact in the field of chromosome and nuclear science, it is almost unrivaled."

Miller told a University Journal reporter in 1996 that induction into the National Academy of Sciences was one of his greatest memories. "The proudest moment," Miller said, was when the academy's president called him "the virtuoso with the electron microscope."

"My wife was smiling, and I blew her a kiss from the stage," Miller recalled.

Miller's academic career led to a number of fellowships and visiting professorships. He was named a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1980. He was visiting professor of biology at the Center of Investigation and Advanced Studies in Mexico City, the California Institute of Technology, the Max Planck Institute for Cell Biology in Heidelberg, Germany, and the University of California, Irvine. He was the Senior Fulbright Scholar at the Division of Molecular Biology, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in New South Wales, Australia.

The esteem felt for Miller by students and colleagues culminated on Sept. 8, 1995, when Miller, then 70, was honored with a day-long symposium, which coincided with the closing of his lab. Called "Oscarfest," the program included a roast and a banquet, and was planned by his students-turned-colleagues, Beyer among them. Oscarfest featured five speakers – four scientists who were part of an international symposium that Miller helped organize in Uruguay some 30 years earlier, and a fifth who was Miller's first U.Va. graduate student.

"They were honoring me because there was nothing left for me to give them other than love," Miller said in the University Journal article.

Miller received the Lifetime Achievement Award in Science from the commonwealth of Virginia in 1997. He retired from U.Va. in 1998 as professor emeritus, but continued to teach his popular course, "Seeing Genes in Action," to first-year students and to advise undergraduates and link them with U.Va. medical researchers.

He told reporters in 1996 and 1997 that in his retirement years, he planned to travel with his wife, write poetry, learn to play the piano, compose "an amateurish sonata," and choose what he wanted read and played at his memorial service.

Miller was born April 12, 1925, in Gastonia, N.C. Prior to his academic career, he served in the U.S. Navy from 1943 through 1946. After earning bachelor's and master\'s degrees in agronomy from North Carolina State University, he was a farmer for six years, and then enrolled in the University of Minnesota, where he earned his Ph.D. in plant genetics. He joined the research staff at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 1961 and began the work that earned him worldwide renown as a molecular biologist.

He is survived by his wife of 63 years, Mary Rose Miller; his sister, Caroline Miller McClintock; his younger brother, the Rev. John Miller; his daughter, Sharon Miller Bushnell; his son, Oscar Lee Miller III; and three granddaughters.

His memorial service will likely be held in March.

— By Rebecca Arrington

Media Contact

Article Information

February 2, 2012

/content/national-academy-sciences-member-and-uva-professor-emeritus-oscar-miller-jr-dies