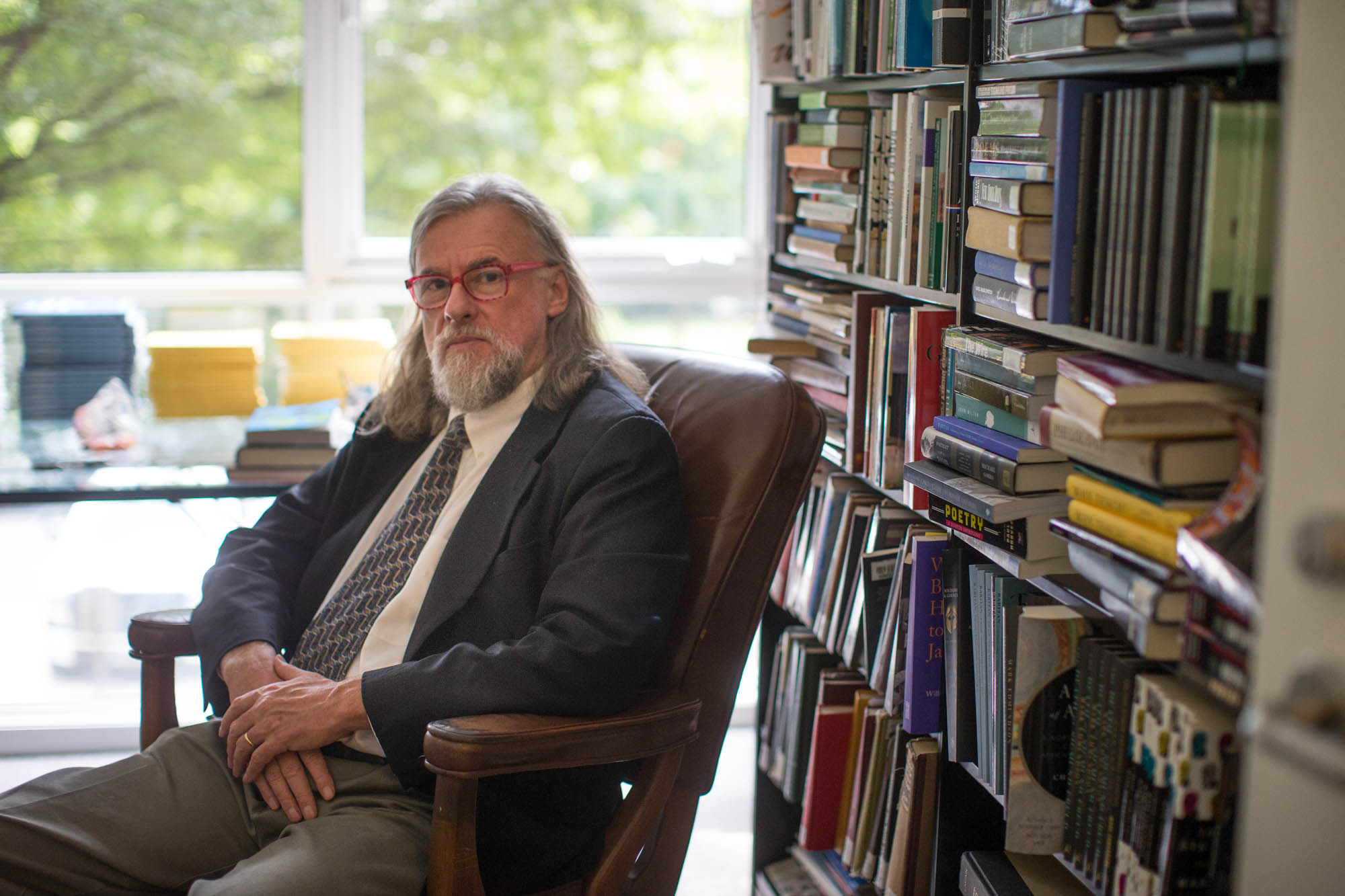

As football season rolls around again, for diehard fans and for players from pee-wees to pros, a new voice has come on the field with a memoir about the meaning of football, “America’s game.” In his new book, “Why Football Matters: My Education in the Game,” University of Virginia English professor Mark Edmundson reflects on his experience as a high school player and discusses what the game teaches young men, for better or for worse.

Edmundson often writes about higher education issues and about teaching the humanities; as a scholar, he also has written about Sigmund Freud, 19th-century poetry and contemporary writers. But he’s also published two other memoirs: “Teacher: The One Who Made the Difference” and “The Fine Wisdom and Perfect Teachings of the Kings of Rock and Roll,” about his high school and early adult years.

“I’m interested in education and expanding the notion of it,” he said, and football fits right in.

“If I hadn’t played football, my life would have been different and (I’m nearly sure) poorer than it has been. I’m certain that I’m not the only guy in America who can say that,” he writes.

Graduate school was not only another form of education, it was another kind of game that had to be played, he found. Working on his dissertation, he came to a point where he had to apply the same kind of determination and perseverance he had learned on the football field, Edmundson said.

After publishing an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education in 2012 on whether sports build character or damage it, he decided to expand the idea into a book reflecting on football as a form of education.

High school wasn’t a happy time in his teen years. He wasn’t particularly athletic, he recalled, but he had learned to love football from his father and wanted to give it a try.

Edmundson played offensive guard and linebacker in his junior and senior years for the Medford Mustangs, near Boston. In the book, each chapter illustrates and illuminates what develops from grueling twice-a-day practices and exhilarating games: character, courage, how to accept losing, patriotism, faith, manliness and loyalty. Stories and insights about fathers and sons frame the book in the introduction and conclusion.

When one of his sons started playing the game at a much younger age, Edmundson – who had long ago traded the bulky pads of the uniform for books, and the gridiron for the classroom – found himself living a bit vicariously, despite knowing he shouldn’t “use [his] son to compensate for past failures,” he wrote.

Watching football with his son, he relived his early days with his father, who was a big fan of NFL Hall-of-Famer Jim Brown. They talked about tackling strategies. At the practices and games, other fathers complimented him about his son, nicknamed “the Pit Bull.” This was a local pee-wee league, with boys 9 to 12 playing.

One of the other fathers was Howie Long, himself a Hall-of-Famer and now television commentator, whose son played on the same team. To have Long compliment his son’s tackling made Edmundson feel redeemed – and more than a little distressed about feeling that way, he writes.

But he also steps back to look at football in a larger, deeper sense.

Drawing on his vast knowledge of literature, Edmundson shines a light on football’s admirable aspects and dangerous pitfalls. He sprinkles in Plato. He discusses the game’s similarities to war, comparing Achilles and Hector from the “Iliad.” Achilles exemplifies the consummate brutal soldier, but Hector, arguably just as courageous and skilled, retains softer traits of humanity – he knows fear and enjoys his son.

“Football is a potentially ennobling, potentially toxic school for the spirit,” Edmundson writes. “When you play the game seriously, you put your soul on the line.”

Still, Edmundson treasures his high school jersey, and he remains a football fan.

From “Why Football Matters”:

“For football is what Plato calls a pharmakon, a poison and an elixir. Football can do great good: build the body, create a stronger, more resilient will, impart confidence, stimulate bravery and cultivate loyalty. ... But football is a dangerous game. The chance of concussion is constant; the repercussions last for a long time. The chance of maiming your body isn’t small, either.

“The dangers of football go beyond physical risk. There is risk to the spirit as well. You can lose more than you gain by being a football player, and the losses aren’t trivial. Football can brutalize a man. It can make him more aggressive, even violent. Too many football players devolve into brutes. Is football courage really courage – or is it all about compensation? Sometime I almost believe that every great ballplayer is a raging Achilles. Does noble Hector, the guy who can turn it off when he needs to, even exist?

“Football is a pharmakon. The game gives and the game takes away and it does so for high stakes. Its potential benefits are vast; its dangers are too. And football may be the most potent form of education that America now offers. ... Football educates for good and for ill, and it’s important to remember that from time to time.”

Media Contact

Article Information

September 3, 2014

/content/new-book-uva-s-mark-edmundson-asserts-football-form-education