Many people could probably name the country that exports the most clothing — it’s China, of course. But what country comes in at No. 2?

A country slightly bigger than North Carolina and, with 163 million people, one of the most populous in the world for its size, compared to North Carolina’s 10 million: Bangladesh.

North Carolina used to be known for making textiles, until companies moved to countries with lower workers’ wages. Bangladesh makes garments with much of the fabric coming from China.

Jennifer Bair, a University of Virginia associate professor of sociology, has been studying “the globalization of supply chains” for 20 years, with a particular focus on labor standards in overseas garment factories. Bair, who joined UVA’s sociology department last year and is its associate chair, recently went to Bangladesh to check on progress in upgrading safety measures following the fourth anniversary of the worst garment factory disaster in history. The collapse of the Rana Plaza factory, where several well-known American and European brands are made, killed 1,134 workers and injured more than 2,000 others in April 2013.

Sociologist Jennifer Bair researches export-led global development, including the clothing industry, as well as gender and work. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

As an undergraduate student, Bair became interested in why development paths differed in Latin America and East Asia. “I became interested in both the similarities and differences in how countries in these regions became integrated into the global economy, and that’s how I started studying global supply chains – or global value chains, as we tend to call them in the development field.”

While working on her Ph.D. at Duke University, she spent a lot of time with textile companies in the Carolinas. They “were just beginning to feel the full force of global competition, because U.S. trade policy had protected the domestic textile producers in the Southeast much more than the apparel manufacturers in the Northeast,” she said.

After NAFTA was implemented in 1994, some companies tried investing in Mexico, hoping it would help them compete with China’s cheaper fabrics. As examples, she mentioned that both Burlington Industries and Cone Mills – both based in Greensboro, North Carolina – went bankrupt and the owner who bought them created a new company, the International Textile Group, that built a mill in Guatemala. That buyer was Wilbur Ross, who recently became U.S. secretary of commerce.

Countries in Asia, particularly China, Bangladesh, Vietnam and India, produce the vast majority of fabrics and apparel these days, but some U.S. clothing imports still come from Latin America, Bair said.

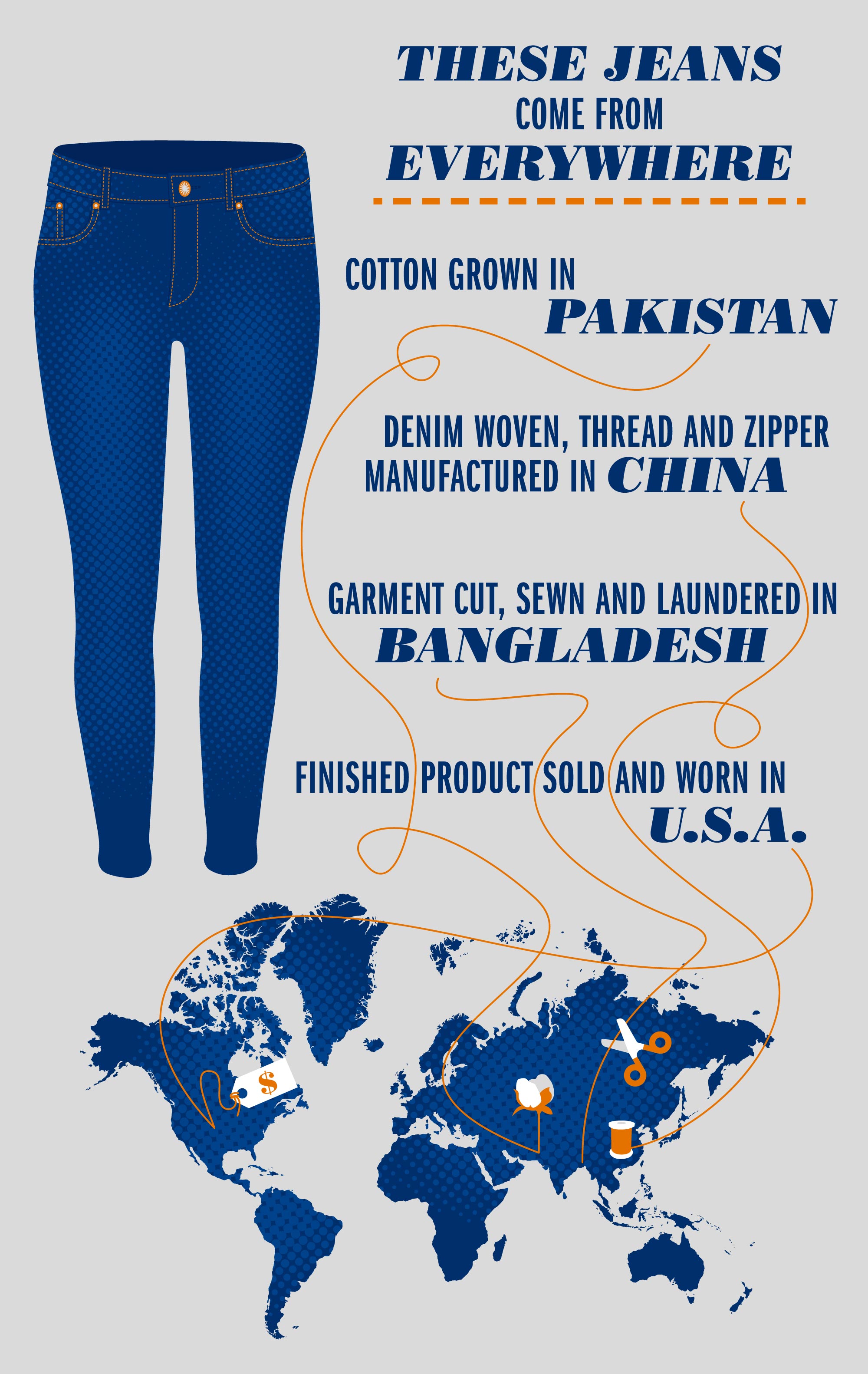

“Take a pair of blue jeans. In that case, the cotton is likely to be grown in Texas, woven into denim in Mexico, sewn and laundered in Honduras and shipped to the U.S. from there,” she said.

In Bangladesh, Bair was the sole academic member of a multi-stakeholder delegation that included representatives from international labor organizations and clothing brands that went to the capital city, Dhaka, to review two high-profile, private-sector initiatives to inspect and remediate hazards in factories there.

“Bangladesh is ground zero around problems of labor conditions in global supply chains,” she said. The Rana Plaza catastrophe was an extreme example, but a movement for workers’ safety was already gathering steam after a series of fires and smaller building collapses that had occurred over the almost 10 years since the garment industry took off in Bangladesh.

After the eight-story, shoddily constructed building in the Rana Plaza commercial complex collapsed, the industry was forced to address safety concerns. About 200 companies, most of them European, and two global unions, IndustriALL and UNI, eventually signed the Accord on Fire and Building Safety, a five-year, legally binding agreement requiring retailers to ensure suppliers in Bangladesh upgrade factories and submit to independent inspections.

Many big American companies chose a different path, opting to join the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. Its inspection program is similar to the Accord’s, but the Alliance does not include unions.

Even if companies are well-meaning and create codes of conduct, volunteer compliance is hard to monitor all along the supply chain. In Bangladesh, the factory owners’ association is very powerful, Bair said, as the garment industry accounts for well over 80 percent of the country’s exports, bringing in $28 billion in 2016.

Bair said she feels somewhat encouraged about the efforts to make some factories safer, but not everything could possibly be fixed by next year’s end of the five-year contract. The Accord has been extended to give more time for finishing repairs and for the government to build the capacity to take over inspections; the Alliance will consider whether to make a similar decision in a couple of months.

“The changes are not done, but there’s more understanding of what needs to be done, especially as younger industrial engineers learn about the initiatives,” Bair said.

She’s also concerned about what’s not in either agreement: core labor standards. “If a country doesn’t have baseline labor rights, that will affect safety,” she said. “If workers have no rights, they’re more hesitant to speak up about safety hazards. There’s a link between respect for their rights and safety.”

Nonetheless, the Alliance has an anonymous workers’ hotline and calls have poured in, even if they often raise concerns that go beyond the initiative’s specific mandate of worker safety. Bair and a colleague from the University of North Carolina plan to analyze the calls to see what workers are reporting. “This is an incredible resource, but we don’t know how long it will last and what will come of it in response,” she said.

The Rana Plaza tragedy was quickly compared to a terrible fire in early 20th-century America that led to reforms in New York City sweatshops. In fact, Bair and two colleagues have published an article about that comparison. When the fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist factory in Manhattan in 1911, 146 people – mostly young Italian and Jewish immigrant women – died from the fire and smoke, some from jumping out of eight- to 10-story high windows that fire ladders in that age could not reach.

The fire led to improved factory safety standards and the growth of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union.

Poor working conditions, low wages and long hours persist in the clothing industry, mostly because there’s great pressure to lower prices to consumers, or keep them low, due to competition from other developing countries with low wages, Bair said.

“Brands say consumers expect cheap clothing,” Bair said. “Anywhere there’s extreme price pressure in the supply chains, there’s the possibility of violations.”

Clothing prices have decreased as factories have moved to places with cheaper labor and tariffs on imports have fallen. “We’re paying less in adjusted-inflation terms than 25 to 30 years ago,” she said.

Bair suggested that millennial customers might be willing to pay more if they know it might help improve labor conditions.

The Rana Plaza collapse has created a new impetus, she said. There is more transparency regarding retailer supply chains in Bangladesh, and that’s a development she hopes other countries and industries will model.

Media Contact

Article Information

July 27, 2017

/content/not-made-america-sociologist-looks-human-cost-cheap-clothing