When Amy LaViers was just 3, her mother and a group of parents in her tiny town in southeastern Kentucky collaborated to bring a dance teacher to the second floor of the fire station to provide lessons for the children.

In the years that followed, LaViers found herself falling in love with movement. She took ballet, tap and modern dance classes, and after her family relocated to a town outside Knoxville, Tennessee, she joined the Tennessee Children’s Dance Ensemble and performed all over the southeastern United States and the world.

To the next generation of a long line of engineers, dance “was an interesting problem to solve,” she said. “Every class is different.”

Today, LaViers, an assistant professor of systems and information engineering at the University of Virginia’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, combines her passions for dance and engineering to conduct research into finding patterns in human movement – and works to apply those patterns to robotics. Her research could have practical applications in manufacturing, such as having robots assist assembly line workers to improve efficiency.

“What I’d love to be able to do is watch a person do a task and have this clear parameterization of the strategies they’re using,” said LaViers, who joined the U.Va. faculty last August. “For example, I’d like to watch multiple people work together on a task and figure out what is different in how they each approach the problem, and then develop a framework, using precise measurements of this behavior, so that a robot could jump in and collaborate too.”

LaViers, whose dad, grandfather and uncles were all engineers, first got the idea to intertwine dance and engineering as a senior at Princeton University, where she earned a certificate in dance and a bachelor’s degree in mechanical and aerospace engineering.

There, in her automatic control course, she had felt completely lost. Then, one day, her engineering professor discussed the concept of stability margins in terms of a bicycle, and she finally felt like she “got it.” Later the same day, she heard a similar discussion of stability in a video by famed dance choreographer Twyla Tharp – and LaViers had an “aha” moment.

“I’m sitting there thinking, ‘I can measure the difference between those difference positions – that could be something we could quantitatively analyze,’” she said.

After several attempts, she found a professor who agreed to advise the proposal for her senior thesis – and that professor, Naomi Leonard, then introduced LaViers to a colleague at Georgia Tech who was working on choreographing movement. Magnus Egerstedt invited LaViers to Atlanta to study with him for her doctorate.

For her dissertation, LaViers choreographed a contemporary dance show called “Automaton” that featured four professional dancers in Atlanta who performed alongside a 23-inch-tall white robot.

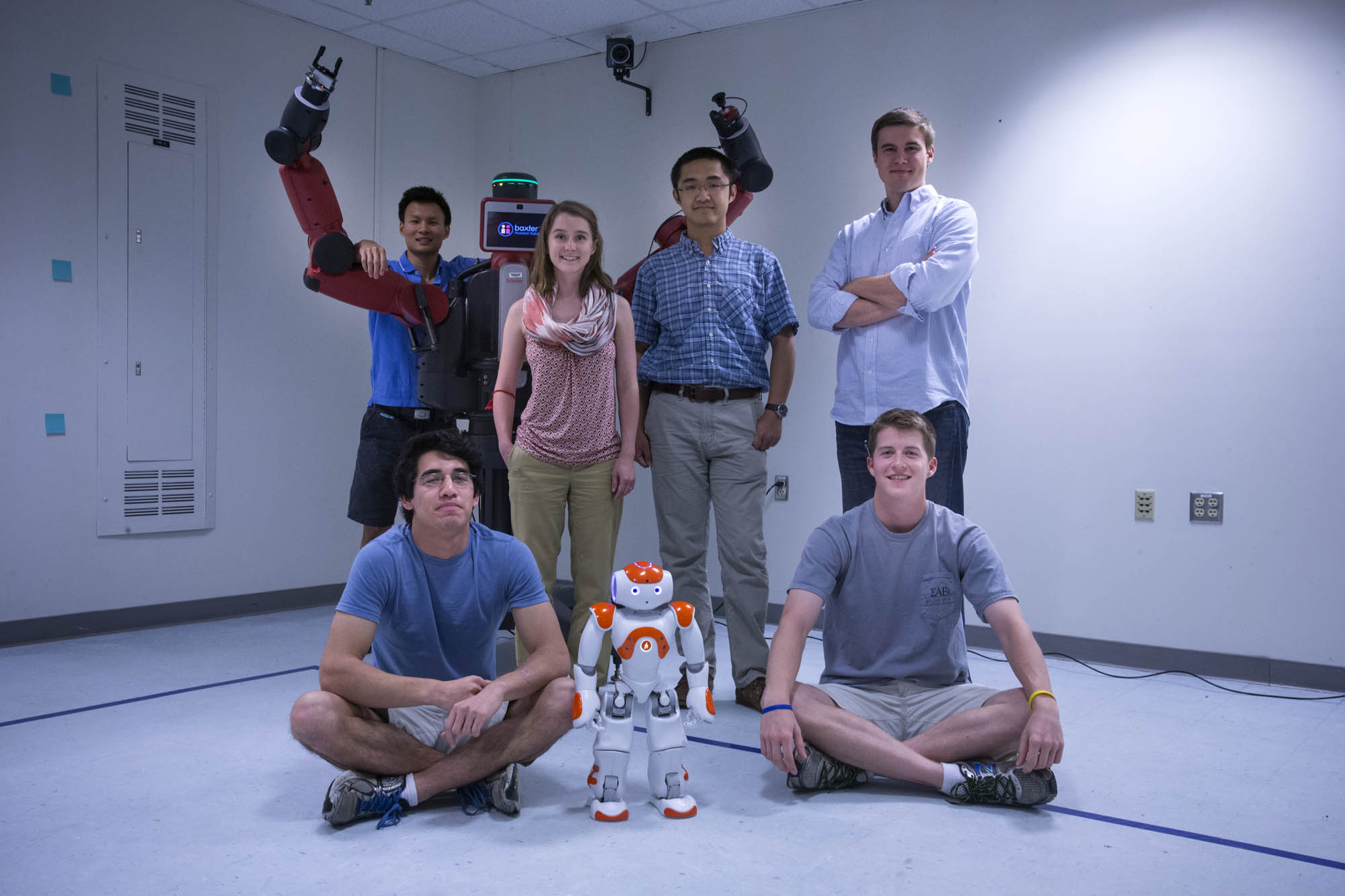

Currently, LaViers is focusing on high-level sequencing questions to apply to the robots in her new lab, which opened in March. For example, she says, “Somebody else figured out how to pick up the phone – lots of people work on that. I want to figure out, ‘OK, do I need to pick up the phone first, or do I need to type on the keyboard first? What’s the sequence of these things, and how should these things be done?’ Similarly, in dance, like in ballet, you have stereotype sequences.”

Her newly published book, “Controls and Art: Inquiries at the Intersection of the Subjective and the Objective,” co-edited by Egerstedt, is geared toward academicians with similar research interests.

As part of a new generation of educators, LaViers aims to lead classes that are experiential -- including an offering funded by the Jefferson Trust that will merge robotics and dance. “I show my students, if you like playing baseball, the strategies you’re doing there, that’s a strategy that we need in engineering, too,” she said.

“It’s much more relevant than I think people realize,” she said. “It’s not just planes, trains and things that go ‘boom.’”

Media Contact

Article Information

June 9, 2014

/content/passion-dance-and-engineering-leads-amy-laviers-robotics-research