There are few words in our history that have captured the American imagination as powerfully as these lines from the Declaration of Independence:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Thomas Jefferson’s stirring declaration that we are entitled not only to life and liberty, but also to happiness has become deeply embedded in the American ethos. It’s also at the center of an ongoing national debate among historians on the proper punctuation of the Declaration.

\"BackStory" contributors, from left, Brian Balogh, Ed Ayers and Peter Onuf tackle intriguing topics from history in their regular radio show. Photo credit: Chris Flynn / NEH

Produced by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, BackStory is broadcast weekly by 173 stations. Funded in part by the University of Virginia, the show features Peter Onuf, the University’s Thomas Jefferson Professor of History, emeritus, and a senior research fellow at Monticello; Brian Balogh, U.Va. Compton Professor of History and chair of the National Fellowship Program at the Miller Center of Public Affairs; and Ed Ayers, president emeritus at the University of Richmond and the former dean of U.Va.’s College of Arts & Sciences.

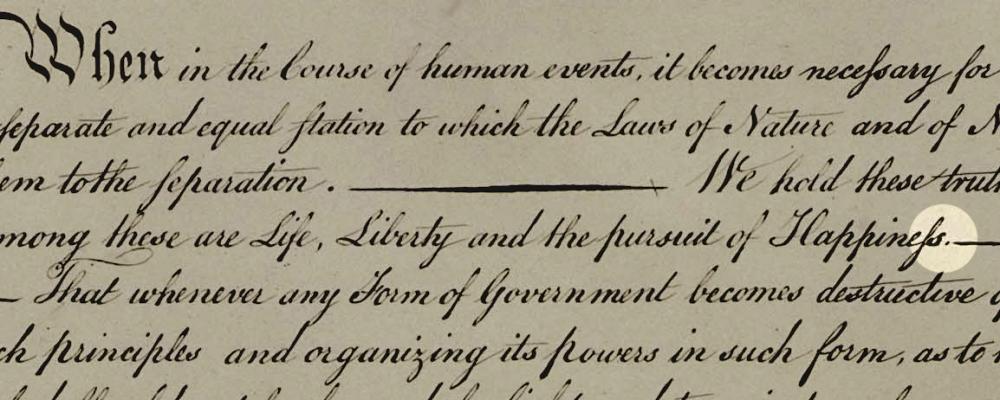

At the heart of their recent discussion is a rather indistinct smudge after “the pursuit of Happiness” in the original handwritten copy of the Declaration of Independence. (All of its contemporary copies were subject to the discretion of the printer.)

Danielle Allen, a Harvard professor and political theorist, argues that the recognized punctuation of the Declaration of Independence, and thus the way we understand it, is different from Jefferson’s original work. Specifically, she says that Americans have been placing a period after “the pursuit of Happiness” when there should be a comma.

Comma supporters suggest it ties our democratic responsibility more closely to our unalienable rights. While we are all born with the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, we cannot secure them unless we establish a government of the people. UVA Today sat down with Onuf, Backstory’s 18th century expert, to get his take on the debate and the Jeffersonian understanding of happiness.

Can you tell us a little bit about the period vs. comma debate in the Declaration of Independence?

Danielle Allen wanted us to take away that if there is a comma, then we don’t stop with happiness, but connect happiness with the frank recognition that government is necessary. That idea still follows with Jefferson’s prose, but we love the idea of stopping with happiness.

Why is it so important to recognize the comma and how it more closely ties the right to happiness with the idea of establishing government?

The two points I’d like to make are that, one, this document is written in a wartime context. Two, it’s meant to mobilize people to fight for the opportunity to determine their own destiny as a people.

Self-preservation is the first law of nature, but people fighting in this war weren’t fighting just to achieve any old peace. They were fighting to take on the opportunities and responsibilities of self-goverment. It’s obvious. It’s ‘self-evident,’ but it’s still hard to understand what it would have meant for the Declaration’s writer and those who were declaring independence and reading it aloud as it rapidly circulated throughout the country. This is not one person’s intention; it is a sentiment and shared faith by a people who weren’t a people until they declared themselves so.

Does reading it with the comma put more pressure on citizens to think about collective happiness rather than individual happiness?

Yes, and I do endorse what Danielle Allen is trying to do. Another way to put that is that you shouldn’t take the word happiness out of context. It has a context. What precedes it and what follows it is important. The whole document is important. Texts are meaningless if they drift without a context.

So it’s safe to say that you’re “Team Comma?”

Yes. I know Danielle Allen, as a teacher, wants students to get the bigger story. This is just a point of departure, a way to go beyond the “happiness!” and ask ourselves more searching questions about what that might mean. In our show, we explored the many contemporaneous meanings of happiness and how they’ve changed over time.

Jefferson was famously inspired by the work of English philosopher John Locke, who believed that men were born with the right to “life, liberty, and estate.” Does this suggest that Jefferson’s understanding of happiness was linked to material goods?

Take that phrase “life, liberty, and estate,” out of Locke’s Second Treatise and ask what that phrase probably would mean to Jefferson or Locke. If you have property, in the context of the revolution, then you have the means to provide for yourself and your family. The household is the major means of production and the place where you do your work. The idea of not being beholden to a landlord as you would be in Britain, means that having your own property is the way you get to participate as a citizen. You have a stake in society.

To substitute happiness for property is not a big deal. In fact it says the same thing, I think because to have property allows to you to provide for the happiness and wellbeing of your family. For Jefferson that is the ultimate happiness, family bliss.

How do you think modern Americans understand the pursuit of happiness?

In a way, I think we’re now reenacting the ideals of the Scottish Enlightenment. Happiness is with and through sociability. We are very aware of mankind’s common predicament.

What’s hardest for us to recover is the idea that we live in world of infinite possibility. We see limits and constraints. For Jefferson and those who died on the revolutionary battlefield, there was always something to look toward. Something new. We had something similar in the 1950s with the space race.

You might say our challenge in pursuing happiness in the future is to overcome the imperfections, the debilities collectively and ask: are we a people? That was the question in 1776.

Media Contact

Article Information

July 30, 2015

/content/punctuating-happiness-jeffersons-declaration-and-truth-our-pursuit