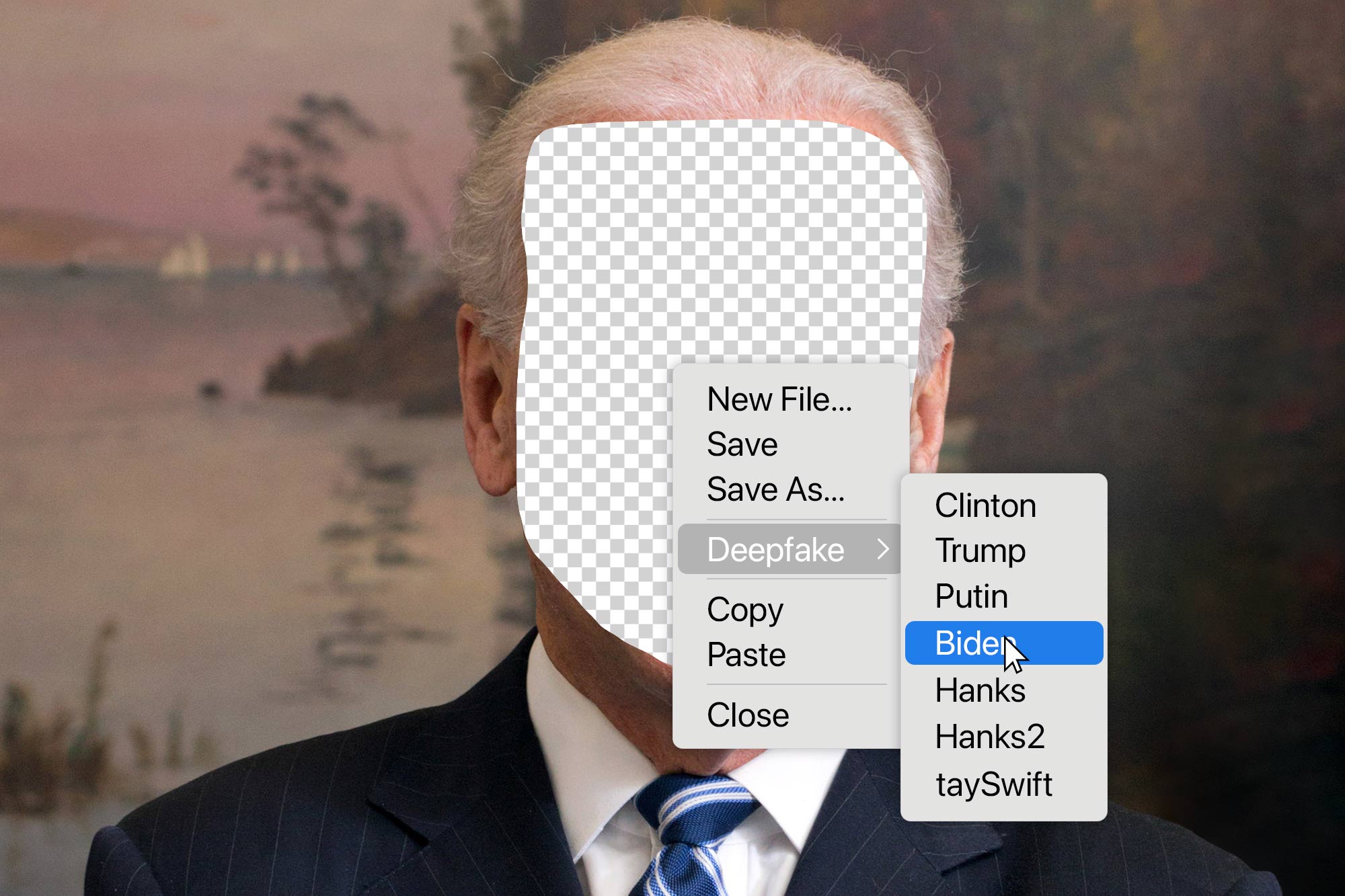

The more deepfakes there are, the harder it is to tell between a fake and a genuine video. But fortunately, a group of library staff at the University of Virginia has created a generative AI guide. UVA Today talked to Multimedia Teaching and Learning Librarian Josh Thorud to learn how to spot differences between deepfakes and authentic content.

Q. When did deepfakes begin to be a problem?

A. The underlying technologies for deepfakes, like machine learning, have been around for a while, but the term was coined around 2017 on Reddit. Shortly after that, some high-profile deepfakes began to surface, along with some major concerns like misinformation, political manipulation and unethical use in creating non-consensual explicit content. And then there is what’s called “the liar’s dividend,” where bad actors seek to weaken our trust in media with fakes, so we feel we don’t know what is true anymore, and use this confusion to their advantage.

Q. Who usually makes them?

A. Deepfakes can be made by anyone with a computer and some free time, and there are many free tools out there. Hobbyists make online deepfakes with humorous, satirical or artistic intentions, for instance, or filmmakers and marketing companies make them to resurrect celebrities or sell products (usually, though not always, legally). However, creators with bad intentions and even foreign governments are making them, too.

The best and most convincing ones still require a lot of technical skills or even a Hollywood postproduction team. This is changing quickly, though, and the free, easy-to-make deepfakes are getting better. Also, new technologies like generative AI text-to-video tools are getting much better by the week. And combine that with generative AI voice impersonation, which can be incredibly convincing and dangerous, [and] we have trouble heading our way from creators with malicious intentions, creating videos that could have personal, legal or global implications. When the well-known deepfake of Ukrainian President Zelenskyy was circulating, telling all Ukrainians to surrender, you could see the implications if it was believed to be true.

Q. Who usually falls for these?

A. Anyone can fall for a well-made deepfake, especially at first glance. But there are some things to look for in a deepfake. Video experts can investigate evidence of being tampered with, and they are the best source for determining if a video is a deepfake.

Q. How can people tell the difference between a genuine video and a deepfake?

A. It is getting harder and harder to pick out deepfakes at a glance, if they are well-made. Sometimes, for the best ones, you’ll need to consult an expert who can look deeper for signs of manipulation. In these cases, you need to use your information and media literacy skills to investigate the source and seek out information on “known” deepfakes through fact-checking websites, reverse image searching and experts.

Q. What are the tell-tale signs of a deepfake?

A. To spot deepfakes, there are a few things to look for: Look for weirdness in facial expressions, or if the lighting on the face doesn’t match the surroundings. For now, most deepfakes are made by putting a digitally modeled face onto another person – either an actor or other footage. So, look for blurring, resolution, color or texture differences between the face and the body, hair or neck. You may even be able to see a sharp line or blurring along where the face has been overlayed. Watch the lips and facial expressions closely for any unnatural movements or anything that feels “off,” especially as they turn their head, or any object comes in front of the face. The tracking or masking may not be perfect in these situations, and it can be hard to get right. Deepfakes do not clone the voice of the person, so they often rely on voice impersonation to sound like the person – which may be less successful than the deepfake itself. This is an area of growth, though, with excellent AI voice impersonation software on the market.

Ultimately, though, your best tool is the same as your best defense against fake news and misinformation in general – sourcing strategies for where it came from, who is posting it and why. Where did the video come from? If it’s from a random social media account or an unknown website, be more skeptical. Reliable news sources or official channels are less likely to share deepfakes. Another thing is to cross-check the information. Look for the same story or video on trusted news sites or through fact-checking websites.

Q. Are there good uses for deepfakes? Can they be used as a learning tool?

A. While misinformation or malicious intent might be behind some deepfakes, there are so many positive uses for deepfakes, including entertainment, art, filmmaking, humor, satire and more. In education, imagine historical figures brought to life for a classroom, or language learning aided by realistic simulations. The key is ethical use and full transparency.

More importantly for the university setting, though, is the educational opportunity involved in learning to create one. By bringing deepfakes into the curriculum, students can critically examine the consequences of this technology and develop their media literacy skills by getting hands-on experience. With the ease of producing fake content today, the real challenge lies in adhering to ethical standards, showing empathy and maintaining integrity.

This underscores the necessity for our educational systems to incorporate ethical reasoning and critical thinking as fundamental aspects of education. It’s crucial for students to critically reflect on the influence of the technology they use in media, societal dynamics and ethical considerations. This approach will not only arm students with media literacy skills, but also ready them to handle and maybe even guide the future.

Q. If you spot a deepfake, what should you do?

A. First and foremost, if you see a potential deepfake on social media, do not share it. Deepfakes often cannot harm anyone if they don’t spread. Secondly, if you see someone else share the deepfake, have the courage to kindly call it out and point to a trustworthy resource such as a fact-checking website, especially for a known and identified fake. It can be difficult to do diplomatically, but as a society we must attempt to fight back. Tell others about how you knew it was fake, so they can learn to spot them, too. Also, you can report it if it’s on a social media platform that allows this function.