During a 1913 address in Richmond, Booker T. Washington praised Virginia’s emerging network of black-owned banks for serving the needs of a disenfranchised community.

“Perhaps in no other section of the country is there a body of Negroes who, on the whole, are more progressive than the Negroes of Virginia,” he said. “Here the first Negro bank was established, and now there are more banks operated by Negroes in Virginia than in any other state.”

A new set of historical records acquired by the University of Virginia Library sheds light on this network of banks and on the important role they played within a marginalized community.

The state’s last Jim Crow-era, minority-owned bank still in independent operation, First State Bank in Danville, recently gave a collection of historical records dating to its founding to U.Va.’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

The records paint a picture of an institution created in 1919 to serve a community that didn’t have access to home or business loans through traditional channels, said Edward Gaynor, head of descriptions in Special Collections.

“For this community, if you wanted access to resources, you had to build your own,” Gaynor said. “You see this in the documents, with this group of middle-class black men coming together and contributing money to capitalize the bank. It was good for them, but also good for the community.”

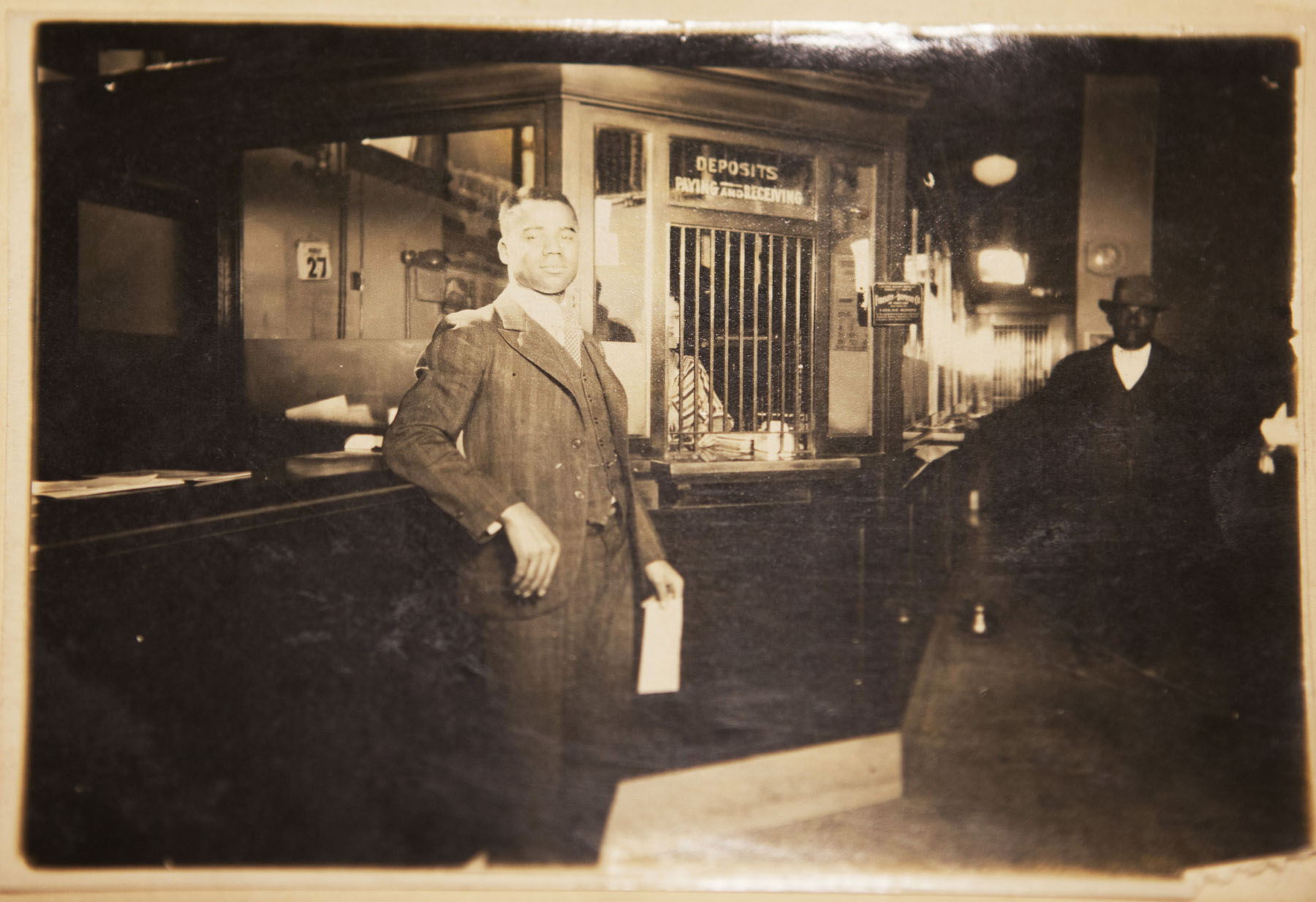

The records include bound loan ledgers with hand-written entries, architectural plans, the minutes of the board’s first meeting and numerous photographs. There are about 40 records in total, all of which are open to the public. Most are from the 1930s and ’40s, though some records continue up through the 1990s. None contain the personal financial information of living customers.

Jeanette Cruz, loan operations manager at First State Bank – now a community bank with a diverse customer base that includes many races and backgrounds – was working at the bank during a renovation in 2006 when she noticed workers tossing a bunch of documents in a trash bin. Cruz stopped them and examined the records, and was surprised at what she found.

“We’re talking about ledgers from the first day the doors opened up,” Cruz said.

She salvaged the records, which included a scrapbook kept by Maceo Conrad Martin, the son of one of the bank’s founders and a longtime president. In the years since, Cruz has delved into the records and even begun giving presentations to area schools and groups about the bank’s history.

“I’ve found that in talking to African-Americans who were born here in Danville, nearly all have some connection to First State Bank,” Cruz said. “That’s amazing to me, that there’s a link that brings them back to the bank, somewhere somehow, either through one of the founders or one of the board members. I feel like First State Bank is one of the cornerstones of the African-American community in Danville, Virginia.”

For the University, the records offer new opportunities for scholarship and teaching, said Petrina Jackson, head of instruction and outreach in Special Collections.

“We have a tremendous collection of materials related to African-American history, and they often focus on slavery – which is incredibly important – and the Civil Rights Movement,” Jackson said. “However, many of these records are in the voices of the people who ran those institutions, not in the voices of the African-American community. These records are in the voice of the people who created and operated the bank. It shows that they were very much entrepreneurial, and were really contributing to their community.”

The records could appeal to students or scholars from a variety of disciplines, including architectural history or Virginia history, and could also facilitate scholarship based on the physical location of Jim Crow businesses or residents.

“This shows a different part of Virginia that we often don’t see, and I think students and faculty can dig into that,” Jackson said.

In addition to what they say about the bank itself, the records illuminate the important role black-owned banks had in Virginia before the national Civil Rights Movement. Some records from the Depression show evidence that the bank was the only thing standing between some customers and destitution.

“If you look at the amounts being loaned by the bank, you will see a $5,000 loan here and there,” Gaynor said. “But you will also see a number of loans for as little as $5 or $10. I suspect this was the bank’s way of helping to keep the community afloat in the depths of the Depression.”

Media Contact

Article Information

March 7, 2013

/content/recently-acquired-records-uva-special-collections-shed-light-virginia-s-black-owned-banks