Among many purposes, the current renovations to the University of Virginia’s Rotunda, the centerpiece of Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village, are intended to make the building more functional for educational uses. Already, the work is offering its own lessons about the building’s history.

The Rotunda has been undergoing much-needed upgrades to its mechanical systems, repairs to its portico roofs and the installation of new column capitals and improved fire and life safety systems, worked scheduled to be completed in the summer of 2016. The work has also yielded up some clues to its past, including the names of some of the people who have worked on and around the Rotunda, how its original oval rooms were configured and how its original dome was covered.

Signatures

Craftsmen often sign their work, and the Rotunda renovations have revealed some of these signatures.

So far, workers’ signatures have been found in the hydraulic cement that lined a cistern in the east courtyard garden; on the McKim, Mead and White-designed capitals currently on the building; and on the bases of the original Jeffersonian columns.

“This is a link to the past, to the people who worked on creating the University,” said James Zehmer, historic project manager for Facilities Management. “We have a historic record of who worked on the University, and finding their signatures helps show their contribution to the physical fabric of the University. This took skill, and they were proud of their work.”

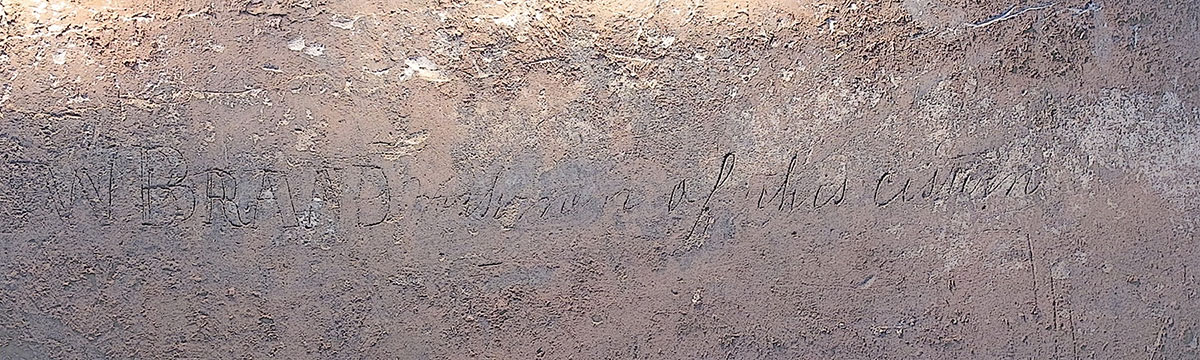

In the spring, archaeologists excavated a 6,500-gallon cistern that had been filled in for more than 100 years, exposing signatures of some of those who worked on the project. The name of mason James W. Brand was found in the hydraulic cement that lined the cistern, along with the name of Charles Carter, of whom almost nothing is known.

“James W. Brand, son of contractor Chiles Brand, is well-known and documented,” said archaeologist Steven Thompson of Rivanna Archaeological Services LLC, who has done work around the University for years. “Charles Carter remains a complete mystery. In all likelihood he worked for Chiles Brand, but I can’t match him to anyone locally in the census. It is possible he was a slave owned by Brand – we know Brand was a slave owner – but there is no evidence to support this.”

Thompson thinks James Walker Brand attended U.Va. from 1853 to 1855 before receiving a degree from the Medical College of Virginia in 1856. Chiles Brand, his father, was paid for brickwork and plastering for three cisterns at the University in 1851, Thompson said.

It was because of the names found in the cistern that Thompson was able to date it. While there were plans in the 1820s to dig cisterns around the Rotunda, records at the University indicate they were not dug until the 1850s.

The cistern, which collected rainwater from the roof of the Rotunda and the south wing, became obsolete in 1886, when the University and the city of Charlottesville jointly funded a more reliable water supply system that used the newly constructed Ragged Mountain dam and reservoir. The cistern was filled in before the 1895 Rotunda fire.

When the cistern was uncovered and excavated this year, the names of the workmen were revealed and preserved. University masons painstakingly removed sections of the cistern wall, building foam-lined boxes around them, then lifting them out of the hole using a tractor with bucket loader on the front.

“The masons wanted to move it by hand, but it was too heavy,” said Mark Kutney, an architectural conservator in the Office of the Architect of the University.

The boxed cistern sections are being kept in storage and may be displayed in the future.

There were also workmen’s names associated with the column capitals, both the originals and their replacements. The name “H. Aherne” was found carved in a capital on a column installed when the Rotunda was rebuilt after the fire.

The capitals installed for the Stanford White vision of the Rotunda were made of domestic marble and were put in place only roughly shaped. Workers on scaffolding carved the capitals in place around 1904, when money was raised to finish them. “We believe the folks who were brought in to work on those capitals were Irish,” Zehmer said.

About three-quarters of an original Jefferson capital survived the fire and currently resides on the patio outside the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia. The capital rests on a piece of an original Rotunda column, and serves as a model for new capitals to be installed as part of the Rotunda's renovation.

When crews removed the top part of the capital, they found the initials “SR” and “F. Brown” engraved into the base. U.Va. preservationists said the names likely date to the Rotunda’s original construction, but the identity of the carvers is still a mystery.

Original Interior Supports Revealed

Workers excavating the floor of the Rotunda’s Lower East Oval Room uncovered remnants of two brick piers, small square foundations spaced equally along the room’s central long axis. They apparently supported pillars, which held up the floor above.

“Documentary research previously done by John G. Waite Associates has found several references to wooden pillars in this room and [the Lower] West Oval [Room], and a desire to replace them with cast iron pillars,” Thompson said. “We have done small probes around both and the archaeological evidence suggests they are probably original features to the Rotunda. Early renovations have reduced both piers, so that what survives would have been below floor level.”

Board of Visitors minutes from 1830 and again in 1843 identify them as being made of wood and raise the possibility of replacing them with ones of iron.

“It is unclear whether they were replaced, though John G. Waite Associates suggest that an 1846 payment for $71.15 for ‘cast iron columns’ may have been for such a replacement,” Thompson said.

While there had been documentary evidence of the columns, finding the piers when the floor was excavated was the first physical proof of them.

“There is a historic letter that indicates there were columns on the lower level, but we were unsure if the footings were still there under the concrete,” Thompson said. “Now we have physical evidence that there were columns in these rooms; we know where they were, and we have a sense of their size. It is particularly interesting to think of how classes might have been arranged in an oval space with a pair of columns in the middle of the room.”

Fire Debris Found in Wall Cavity

The 1895 fire was thought to have left no traces of the building’s iconic dome, but University masons working on the renovation discovered pieces of that structure preserved within the walls.

The original dome structure was wooded and likely would have been destroyed in the fire. Its roofing was made from tin-coated iron shingles.

Kutney was part of the team that opened cavities in the walls of the lower oval rooms, seeking evidence of original design features. They found debris from the 1895 fire and the Rotunda’s subsequent reconstruction, giving further insights into the original building’s construction and maintenance.

“We found a lot of glass, window glass, melted and broken into pieces, and we found pieces of sheet tin that appear to be material from the roof,” Kutney said.

The shingle pieces Kutney found in the wall cavities were joined together with folded-over edges, a technique designed by Jefferson and used on several roofs within the Academical Village. The original dome would have been shiny at first before weathering to a dull gray and eventually a chalky white. Some of the surviving shingles had red paint on them, indicating that at some point the dome was painted red.

“They may have added some solder (a soft metal alloy with a low melting point) around the nail holes and they also used white lead as a caulk on the nail holes and the joints on the more shallow pitches,” Kutney said of the original dome.

As the caulk – a combination of white lead, whiting and linseed oil – dried, it became brittle and would have broken apart, Kutney said. Once the roof started to leak, Kutney believes the dome may have been painted in an effort to halt its corrosion.

“The dome would have been problematic in its shape,” Kutney said. “The wind and the rain would have pushed water up and under the shingles.”

Kutney thinks the hue on the shingles is what was referred to as “Spanish brown,” a combination of iron oxide and linseed oil. That red paint on early tin was found in other locations, such as Hotel A, and the original gutters on the student room roofs, he said.

Photographs of the Rotunda from the 1880s show a darker dome. In black-and-white photographs, red would appear to be a darker shade.

Some of the newly discovered shingle pieces appear to have been painted on both sides. Matt Scheidt, a historic architect with John G. Waite Associates of Albany, New York, which has performed historic assessments of the Rotunda and the Academical Village, suggested the dome may have been re-shingled at some point, with the second layer already painted on both sides as a protective coating.

“These shingles are ones that were on the dome right before the fire,” Scheidt suggested. “If they put a new roof on, they would likely have put over the existing one, so it is possible that some of the original roof survived.”

Workers also found what appears to be a timber bracket – a 52-inch piece of wrought iron that fit perpendicularly into a set of four 32-inch-long legs that would have anchored it into a brick wall. The long piece of iron, hand-cut with beveled, has square holes punched into it at 13-inch intervals. Kutney said there was still some plaster attached to one of the legs. The bar would have been anchored in the wall and then bolted, probably lengthwise, to a joist to give the joist or beam support and to tie together the floor framing and masonry wall.

Scheidt speculated the piece may have supported the ceiling joists in one of the upper oval rooms. He thought the joists would have needed additional support because they held up the columns in the dome room.

Also in the fire debris were several hand-wrought carriage bolts and numerous bolt heads, which Kutney said could have been part of the framing of the dome. There were also a variety of machine-cut nails.

The fire debris in the cavity included pieces of brick, mortar, shards of glass, plaster, pieces of iron, tin, chunks of charcoal and ash. Workers removed a few buckets of material, but left the rest undisturbed and resealed the wall, Kutney said.

“We want to leave something for the next generation,” he said.

Media Contact

Article Information

December 19, 2014

/content/rotunda-work-uncovers-clues-its-history