Civil rights history in America will forever be defined by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have A Dream” speech, delivered 50 years ago on the National Mall. Yet the foundation upon which the Civil Rights Movement was built and the arenas through which it spread have been the result of many great leaders, some well-known and others lesser so. Among the latter was the Rev. John M. Perkins.

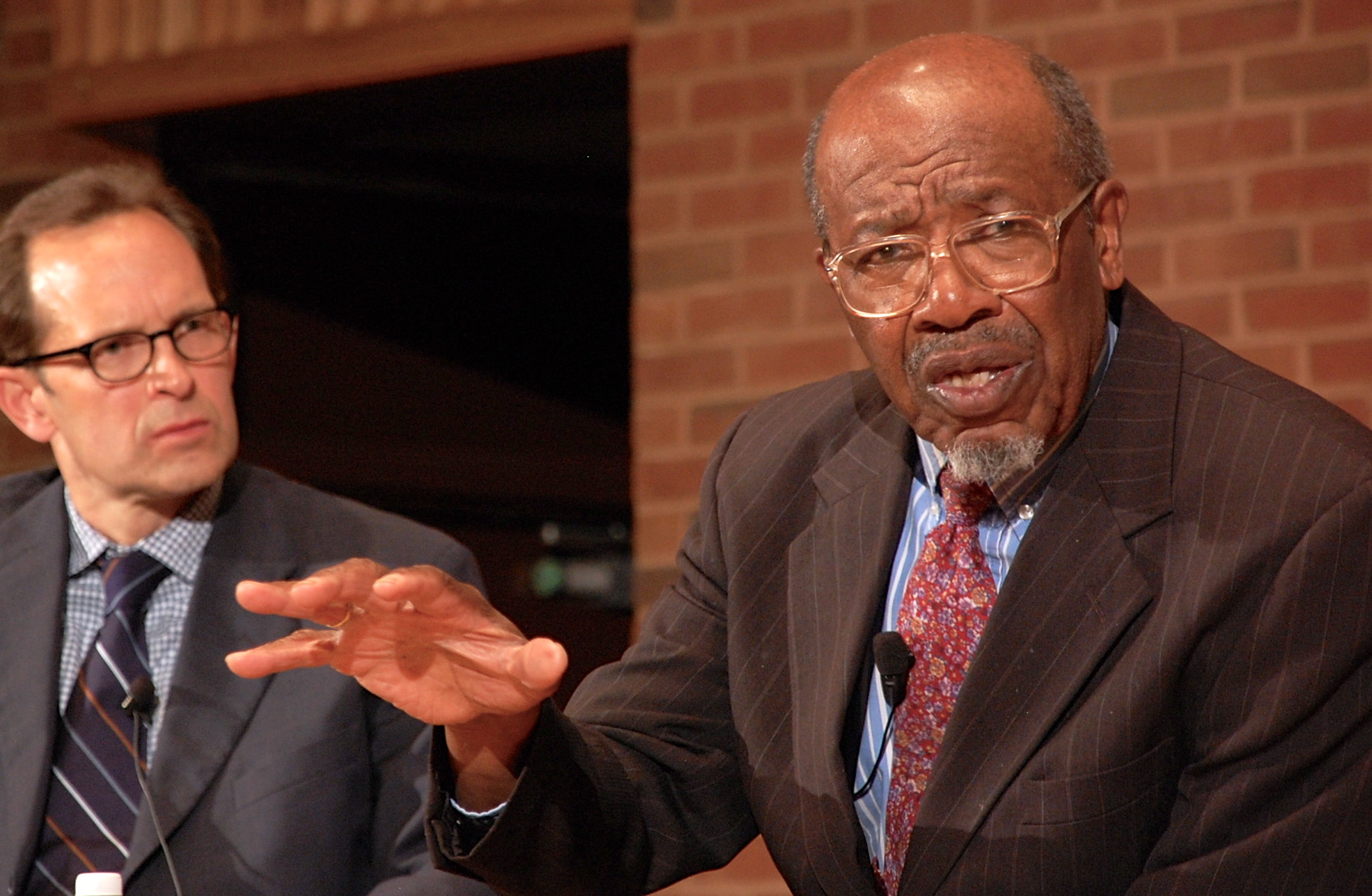

But that may no longer be the case. Perkins’ life and the theological and historical context of his work have been revived in a new book by Charles Marsh, a religious studies professor in the University of Virginia’s College of Arts & Sciences, written with U.Va. Ph.D. graduate Peter Slade and Peter Heltzel, associate professor of theology and director of the Micah Institute at New York Theological Seminary.

Born in Mississippi in 1930 into a sharecropping family, Perkins faced a childhood of economic disadvantage. He received only a third-grade education and lacked a strong faith base until later in his life. Following a conversion experience in California in 1957, he began to gravitate to evangelical Christianity. Returning to Mississippi in 1960, he began pushing for African-American social justice and challenged white churches to engage the difficult work of racial reconciliation, Marsh said.

Unlike many African-Americans of the time, Perkins was accepted into the white evangelical church. According to Marsh, Perkins’ acceptance was guided by his willingness to call himself an evangelical, his ability to relate to white church members by using their language and by inviting people to work with him in low-income neighborhoods.

Perkins did not believe it was enough to save individuals, but instead hoped to save the social structure, Marsh said. By establishing interracial Bible groups and encouraging whites and blacks to worship together, he sparked a transformation in the South.

Since the late 1960s, Perkins has ushered in a paradigm shift within evangelical churches. He “offered the good news that the religion of Jesus has far bigger implications than simply offering personal salvation – that the church is more than a safe haven from the evil world for the believer while they wait for the Second Coming,” Slade said.

Perkins’ impact on Southern evangelical churches drew Marsh to study him while a student at Harvard University.

“As a white Southerner who inherited the baggage of white supremacy,” Marsh said he felt guilty. In the summer of 1980, Marsh journeyed to Mississippi to not only hear Perkins’ story, but to lend a hand to the movement and confide in a confessor who would allow him to unburden his guilt.

“We have been very good friends since that summer,” Marsh said.

As Marsh’s academic career advanced, he continued to follow Perkins’ work while seeking to “adequately bridge the world of academic training with complicated social context and situations in real life.”

As Marsh explored conceptions of God in a range of groups, from members of the Ku Klux Klan to African-Americans involved in the Civil Rights Movement, he looked to Perkins for an understanding of one perspective, Marsh said.

In 2009, Marsh and the U.Va. Lived Theology Project invited Perkins to be the keynote speaker at the Spring Institute for Lived Theology. The annual gathering of theologians, scholars and practitioners focused on issues of faith and social practice proved to be a springboard for deeper analysis of Perkins’ life and impact, ultimately leading to the publication of “Mobilizing for the Common Good: The Lived Theology of John M. Perkins.”

The book features contributions from historians, theologians, community organizers and activists. Divided into three sections, it takes the reader through the life of Perkins within the church and the impact he had on evangelicals.

Slade, now a professor at Ashland University in Ohio, explains that the first section gives readers an “understanding of Perkins’ place in the context of the history of the American church in the 20th century. The second section explores the life and theology of Perkins in conversation with academic theology and biblical studies. The third section considers the way the work of John Perkins points academics and practitioners in fruitful directions.”

As “Mobilizing for the Common Good” explains, Perkins’ work did not end when the Civil Rights Movement faded; instead, 40 years later, John Perkins is the founder and spiritual leader of the Christian Community Development Association, a network of more than 1,000 churches and ministries working in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods aiming to “release church from ‘cultural captivity and repressive materialism.’”

Today, Perkins continues his work as a civil rights activist, preacher and community developer. He continues to live in his poor community and address a range of social issues grounded in his faith.

— by Sarah Patterson

Media Contact

Article Information

October 3, 2013

/content/scholars-book-sheds-light-civil-rights-activist-john-m-perkins-impact