Evidence of Thomas Jefferson’s architectural ability abounds in Charlottesville, a city that sits in the shadow of Jefferson’s home, Monticello, and proudly features his Academical Village – collectively, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

While the University of Virginia’s Rotunda might be Jefferson’s most beautiful, iconic creation – we’re admittedly biased – the third president left his architectural fingerprints all over the state of Virginia and the early United States of America.

A new exhibition at The Fralin Museum of Art at UVA, “From the Grounds Up: Thomas Jefferson’s Architecture and Design,” chronicles this extensive influence. The many letters, hand-drawn plans, books and models on display testify to Jefferson’s love of architecture, as does a Jefferson quote emblazoned on the wall: “Architecture is my delight and putting up and pulling down is one of my favorite amusements.”

“He lived in a construction zone his entire life, always remodeling wherever it was he lived,” said Richard Guy Wilson, Commonwealth Professor of Architectural History, who curated the exhibition.

Unfortunately, it seems Jefferson did not think much of American architecture at the time, writing in his “Notes on the State of Virginia” that “The genius of architecture seems to have shed its maledictions over this land.” He began a lifelong quest to bring the classical architecture he loved in the Old World to the new one being built in America.

“He was really out to reform American architecture and create something new,” Wilson said.

Below, we examine five lesser-known buildings in Jefferson’s portfolio that still stand today as examples of his ongoing impact on American architecture. Take a look and make sure to visit the exhibition, presented as part of the University’s bicentennial celebrations. It will run through April 29.

The Virginia State Capitol

Jefferson was commissioned to design the Virginia State Capitol while still living in Paris as the newly minted American ambassador. He recruited French architect Charles-Louis Clerisseau to the project, and the pair based their designs on the Maison Carée, a classical Roman temple in Nimes, France. That choice reflects both Jefferson’s longstanding admiration of classical architecture and his determination, in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War, that American architecture should aspire to similar greatness.

Jefferson modeled the Virginia State Capitol after a favorite classical temple in France. (Photo by Doug Kerr, published under Creative Commons)

Wilson called the Virginia State Capitol “Jefferson’s most important building – not necessarily his greatest, but his most important.” It was the first public building built in the U.S. after the Revolutionary War and epitomized Jefferson’s vision for the new country.

“This became the model for American public architecture for many years,” Wilson said.

The United States Capitol

As George Washington’s secretary of state – a Cabinet position that at the time focused on internal affairs instead of international relations – Jefferson was involved in much of the planning and design of Washington, D.C.

Jefferson took on an active role in the planning and design of the U.S. Capitol and the nation’s new capital city. (Image: Architect of the Capitol)

Though he did not directly design the United States Capitol – that distinction belonged to several other architects – he created a series of sketches that influenced the final design of the building and mediated proposed changes to the original plans.

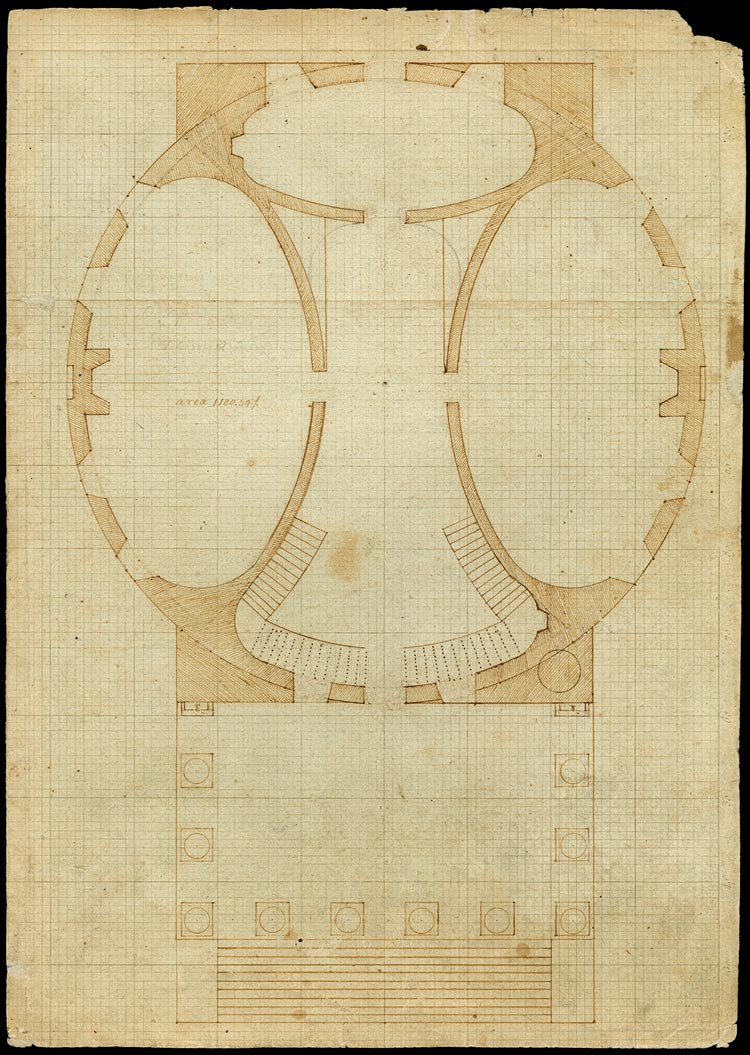

Jefferson’s Rotunda drawings resemble a U.S. Capitol layout he planned. (Thomas Jefferson University of Virginia, Rotunda June 16, 1823 (N-330). Thomas Jefferson Papers, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia)

“He was very involved in laying out Washington, D.C. and planning different buildings in the new capital city,” Wilson said.

As Wilson points out in the exhibition, Jefferson’s sketches for the Capitol – featuring a grand, circular central dome – echoed his plans for a dramatic centerpiece at the University of Virginia.

The East Wing of Farmington Country Club

Farmington Country Club sits on an idyllic plot of land just a few minutes away from the University. Though today it houses a members-only clubhouse and golf course, in Jefferson’s time it was a private estate, purchased by his friend George Divers in 1785.

Jefferson’s East Wing still stands at Farmington Country Club. (Photo courtesy Farmington Country Club)

Divers asked Jefferson to design an addition to the original house, and Jefferson came up with an octagonal east wing reminiscent of his designs for his own home, Monticello. The wing – now known as the Jefferson Room – was built in 1802 and still stands today.

Poplar Forest

Monticello was not Jefferson’s only home in Virginia. He also owned Poplar Forest, an estate in Bedford County he inherited from his wife Martha’s father. The working plantation – fueled by slave labor – provided the family with significant income and a secluded private retreat.

Wilson said that Jefferson’s renovations at Poplar Forest represented “Jefferson’s ideal design.”

Jefferson designed Poplar Forest as a peaceful getaway from the bustle of his work at Monticello and in Washington. (Image courtesy of Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest)

“He tried to create a villa that was mathematically correct, with a perfect octagon shape,” Wilson said. “Then, at the center, a perfect cube space served as a dining room.”

The exhibition contains both original and replicated materials illustrating the design and construction methods used at Poplar Forest, which remain instructive today.

“The restoration of Poplar Forest since the later 1980s has helped change the nature of architectural reconstruction, as they have attempted to use original materials and tools,” Wilson said.

Charlotte County Courthouse

Jefferson’s architectural prowess, it seems, was not limited to one branch of government. He designed three courthouses in Virginia. Only one, the Charlotte County courthouse in south central Virginia, survives today.

The Charlotte County courthouse is one of three courthouses Jefferson designed in Virginia. (Image: Commander Shepard247, Creative Commons)

The exterior resembles that of the Academical Village and Monticello: an imposing red brick building adorned with white columns and hunter green shutters. Jefferson’s designs for the interior, however, were a bit different from what we see in courthouses today, as a floorplan displayed in the exhibition shows.

Jefferson’s plan positions the jury box directly behind the judge, keeping the jury front-and-center rather than off to the side.

It’s a reminder, Wilson said, that the men and women of the jury – ordinary citizens – “have the ultimate decision in the matter.”

Media Contact

Article Information

February 7, 2018

/content/there-are-uva-and-monticello-do-you-know-jeffersons-other-buildings