The items in the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library span four millennia, from Babylonian clay tablets dating to around 2000 BCE to poetry published this spring using a 3-D printer.

But there’s been a real gap in the library’s holdings: It hasn’t owned a manuscript written in the three-millennium period between the library’s clay tablets and its earliest parchment manuscript fragments.

Until now, that is.

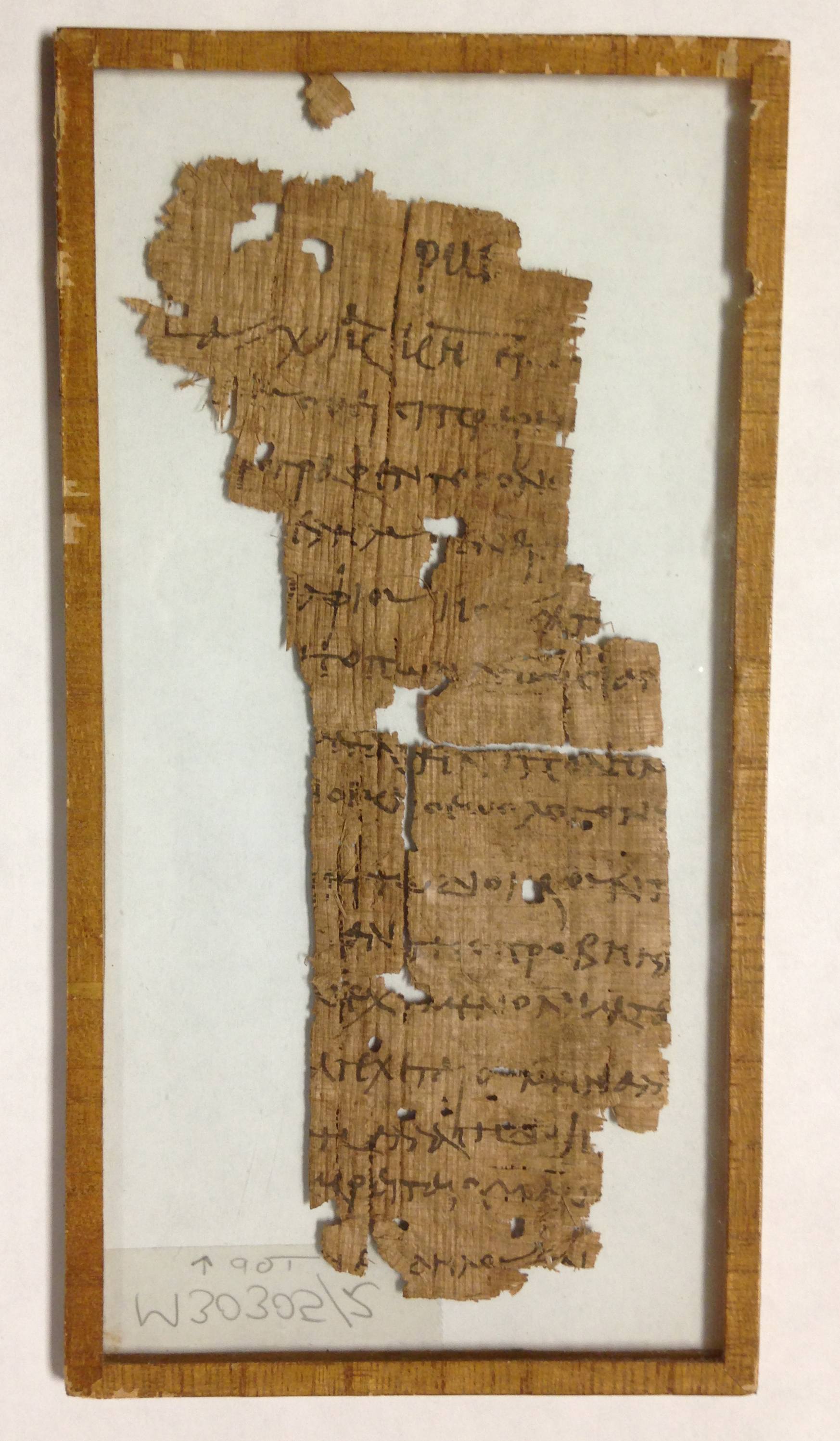

This month, the Special Collections Library purchased its first original manuscript from classical antiquity, a papyrus document from Egypt tentatively dated to the third century CE. It was purchased at a public auction conducted by Swann Galleries in New York City on March 19, 2015.

Although not complete, the document – designated as P. [for papyrus] Virginia 1 and measuring 16.5 x 8 cm. – is a good representative example of its kind. Probably originating in a region southwest of Cairo, the Greek text may be a receipt or tax document concerning grain.

“A papyrus document has long been a desideratum for us,” said David Whitesell, curator of the Special Collections Library and faculty member at the Rare Book School, where he teaches courses in pre-1800 printed books and descriptive bibliography. “This example will be useful in helping us to interpret the early history of the book and the history of the Greco-Roman world to U.Va. students, faculty and the general public.”

According to Whitesell, faculty members in U.Va.’s Department of Classics are already studying the text and planning student practicums around it for the coming academic year.

Papyrus was employed as a writing surface in Egypt by 2500 BCE. It was widely used throughout the Mediterranean and Near East from around 500 BCE up to around 1000 CE, when it was replaced by parchment and paper.

Papyrus sheets were formed from the stem of the papyrus plant; after polishing, the sheets were either pasted together to form a scroll or used individually. Employing a reed pen, scribes would typically write on the “recto” side, or the front side, which was usually smoother.

Few of the many millions of papyrus documents written over the millennia have survived to the present day.

Nevertheless, over the past 125 years, an impressive corpus of papyrus texts has been published. Tens of thousands of such texts have been digitized and placed online at Papyri.info, furnishing papyrologists with tools for comparing texts and readings, as well as for locating fragments of the same document scattered in collections around the globe.

The majority of surviving papyrus documents have either come from the desert areas in Egypt, where many had been buried by sand until they began to be excavated in the late 19th century, or from mummy wrappings (papyrus documents were frequently recycled, and therefore preserved, in this fashion).

According to Whitesell, most surviving papyrus documents are fragmentary in nature, having been torn, crumpled, nibbled or otherwise damaged at various points over the centuries.

“Even in fragmentary state, papyrus documents have a great deal to tell us about the cultural, economic, political and social history of the Ancient World,” he said.

Papyrologists receive specialized training in the skills necessary for working with and deciphering these documents. To begin that process, the papyrus pieces must be cleaned and flattened, with fibers straightened and fragments aligned before the texts can be studied in full. Sealing them between two panes of glass greatly facilitates their handling, study and long-term preservation.

According to Whitesell, in transcribing and translating the documents, papyrologists face the problems of missing text, poor handwriting, faded or flaking ink, variable spelling and grammar, unfamiliar vocabulary and local dialects.

But now, with an actual papyrus document held in the Special Collections Library, such hands-on textual work can be incorporated into the U.Va. classroom experience. “As a representative example of its kind – and of the challenges these documents pose for papyrologists – P. Virginia 1 will help U.Va. students develop the skills necessary for studying these texts,” Whitesell said.

Media Contact

Article Information

May 27, 2015

/content/uva-acquires-its-first-original-papyrus-manuscript-ancient-world