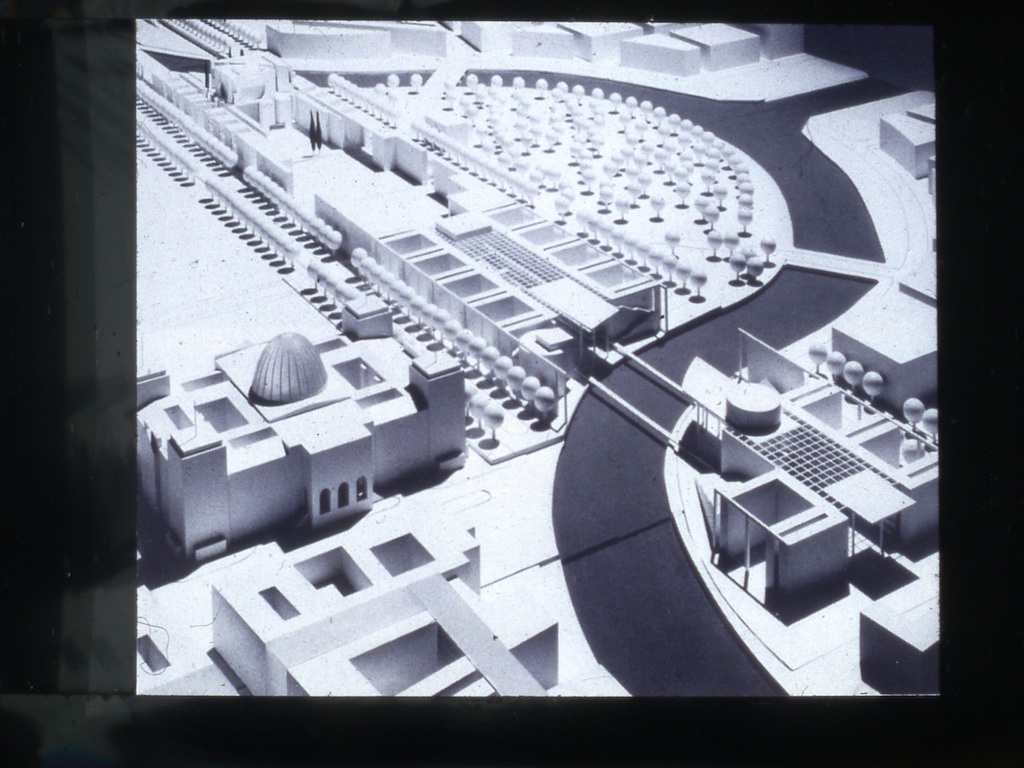

One week after the Berlin Wall fell on Nov. 9, 1989, Karen Van Lengen arrived in Berlin to present what would become her winning entry in a design competition for the Berlin Public Library.

The friend’s apartment where she was staying offered her an angle on the aftermath of the historic event that few people would ever have, allowing Van Lengen to film the celebrations that occurred immediately after the wall fell.

As part of next week’s Berlin Wall Symposium at the University of Virginia, Van Lengen, Kenan Professor of Architecture at U.Va. and former dean of the School of Architecture, will combine this trove of her footage – never before shown in public – with a collection of rare artifacts, to tell her personal story of a land celebrating its new freedom. The presentation will take place Tuesday at 5 p.m. in Campbell Hall, room 153.

The symposium will celebrate the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall with lectures, panel discussions, theatrical and dance performances, art projects, film screenings and photography exhibits.

Van Lengen will also offer insight into her experience as one of only two American judges (along with celebrated architect Richard Meier) to judge the 1993 Spreebogen Competition in Berlin, an event architects recall as one of the most important architectural competitions of the 20th century, she said. There, the jury selected the planning design for the unified Germany’s new government center following the capital’s move from Bonn to Berlin.

In a place that for decades had been defined by two distinct sides – east and west − some of Van Lengen’s strongest memories of the fall of the Berlin Wall are found in the middle.

“In those early months, the wall was still up,” she said. “People came to chip away at it from both sides. Everyone wanted a piece of the wall, especially the Western side where so much graffiti had decorated the wall for years.”

The Berlin Wall was actually two walls with a dangerous space between them. The space was marked by East German guard towers that had continuously watched for East Berlin escapees, who would be shot should they try to cross.

After the historic fall on Nov. 9, “Holes began to emerge, and small windows into the interior space began to reveal the inner terror of the walled space,” Van Lengen said.

The walls came down in sections. First, one wall was taken way, and Van Lengen could see the landscape to the other side. As the wall was being dismantled, Van Lengen would watch as people were being allowed to walk through the once heavily guarded areas.

“This was an enormously psychological space, because just six months before, the wall had been one of the most dangerous places in the world,” she said. “You would have been shot down in a minute.

“Now, suddenly, you were walking freely there in the inner landscape as if it were a park. That was a very strange emotion, watching people cross back and forth with ease.”

Mixed in with those emotions for Van Lengen are the kinds of sensory memories that come from being on the front lines of history. Returning to Berlin nearly every month to work on the Berlin Library planning, while staying in one of the few remaining buildings standing in the shadow of the Berlin Wall, Van Lengen did more than just watch history. She heard it. And she felt it.

Her nights were filled with the sounds of people chipping away at the wall.

“All those towers that once had the East German guards in them, they were starting to be dismantled, and you could see over the wall. You could see the other side. And every night, I could hear the ‘tick, tick tick’ of someone chipping away at the wall.”

Van Lengen began to gather her own remembrances. For her, collecting small colored chips from the remains of the wall was like finding gold that she felt would eventually be completely gone.

“I would find these chips that had color in them, that had been graffiti,” she said. “And even at the end, when the wall was almost gone, every once in a while, I would see a little chip of color and pick it up. I became aware through this process that history was not only being made, but that it was now progressing.”

Van Lengen had a front-row seat to some of the progress being made at that time when she was one of the jurors on the competition to design Germany’s unified government center.

“I had the opportunity to listen to the federal government jurors and the local jurors from the city government, along with international architects, discuss what should represent a unified Germany,” she said. “That was fascinating, and it was an enormous privilege to be a part of it.”

When all the guard towers were dismantled, Berlin set out to quickly erase its past – connecting streets, neighborhoods and sidewalks from opposite sides. As she had been acutely aware of the wall’s presence, Van Lengen began to contemplate its absence.

“I watched the way history was going to try and erase this particular dominant structure,” she said. “There is almost nothing left of the Berlin Wall anymore. Whenever they could, they tried to paint it over and unify it so that it was no longer there. They were very fast in wanting to do that.

“It is even difficult to imagine today what that walled condition was like.”

Media Contact

Article Information

October 30, 2014

/content/uva-architecture-professor-shares-memories-berlin-wall-s-fall