One hundred years ago, an idealistic, adventure-seeking, young American named James R. McConnell was shot down in a World War I dogfight over France. He is still being remembered at the University of Virginia.

McConnell, who had been an undergraduate and a law student at UVA, traveled to France in 1914 to join the fight against Germany, three years before the United States became a combatant. He volunteered to drive an ambulance, and received the French Croix de Guerre for rescuing a wounded French soldier under fire.

Later, McConnell and several other ambulance drivers formerly affiliated with the American Field Service, seeking a more active role in the combat, founded the Lafayette Escadrille, an all-American air squadron flying biplanes against the German forces. He was shot down March 19, 1917 in an encounter with two German aircraft, earning the distinction of being the last American pilot killed in the conflict before the U.S. entered the war.

McConnell, the inspiration for “The Aviator” statue on the plaza at Clemons Library, is being remembered on March 16 with a ceremony and speeches in the Harrison Auditorium and at the statue itself. UVA President Teresa A. Sullivan, University Librarian and Dean of Libraries John Unsworth, and Edwin Fountain, vice president of the national World War I Commission and a School of Law alumnus, will speak. Members of McConnell’s extended family have been invited to attend.

James McConnell, who flew for France, was the last American pilot to be killed in World War I before the U.S. joined the fighting. (Photo courtesy of UVA Library)

The University’s Air Force ROTC unit will play a major role in the ceremony. A color guard will present and post the colors before the ceremony begins, and following a wreath-laying ceremony, Cadet Grey Davenport, a fourth-year math major bound for pilot training following his graduation in May, will offer a toast to his fallen comrade.

The Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library will host an exhibition of McConnell’s letters and artifacts, including a piece of McConnell’s biplane, shell fragments and one of McConnell’s caps. The Special Collections exhibit will run through May 21.

“Our collection contains letters from McConnell to his friend, Paul Rockwell, describing in graphic detail what he saw in the trenches and how soldiers and civilians coped,” Special Collections curator Molly Schwartzburg said. “He was not just an idealistic young man in search of adventure when he joined the flying corps. He had experienced grave danger already, and he expected that he was going to die.”

McConnell was born in Chicago on March 14, 1887, the son of Judge Samuel Parsons McConnell and his wife, Sarah Rogers McConnell. The family moved to New York City, then to Carthage, North Carolina. McConnell attended private schools in Chicago; Morristown, New Jersey; and Haverford, Pennsylvania.

He enrolled at the University of Virginia in 1908, spending two years in the College of Arts & Sciences and a year in the Law School. At UVA, he founded an “aero club” and engaged in numerous collegiate pranks. He was elected “King of Hot-Foot Society” – later in France, he would paint a red foot on the fabric of one of his airplanes – and was a cheerleader and a member of Beta Theta Pi fraternity.

McConnell left law school before graduating and returned to Carthage, where he worked as the land agent of the Seaboard Air Line Railway and secretary of the Carthage Board of Trade. He wrote promotional pamphlets for the Sandhills area of North Carolina. He never married.

After the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914, the adventure-seeking McConnell joined the American Ambulance Hospital Field Service and went to France.

McConnell believed America needed to do more in the war against Germany, so he resigned from the Field Service to become one of 38 founding pilots in the Lafayette Escadrille, or squadron. Flying Nieuport biplanes that traveled at around 110 miles per hour, McConnell’s subset of the squadron consisted of six pilots and 70 ground personnel.

Initially, the pilots were issued machine guns, which they fired with one hand while flying the airplane with the other, and with their feet. Later, McConnell was given an airplane outfitted with a 500-round Vickers machine gun synchronized to the propeller of the plane.

McConnell was wounded once and narrowly escaped death several times before his final battle; while recovering from a back injury incurred during a landing mishap, he wrote a book, “Flying for France,” about his exploits. He was killed a few days after his 30th birthday.

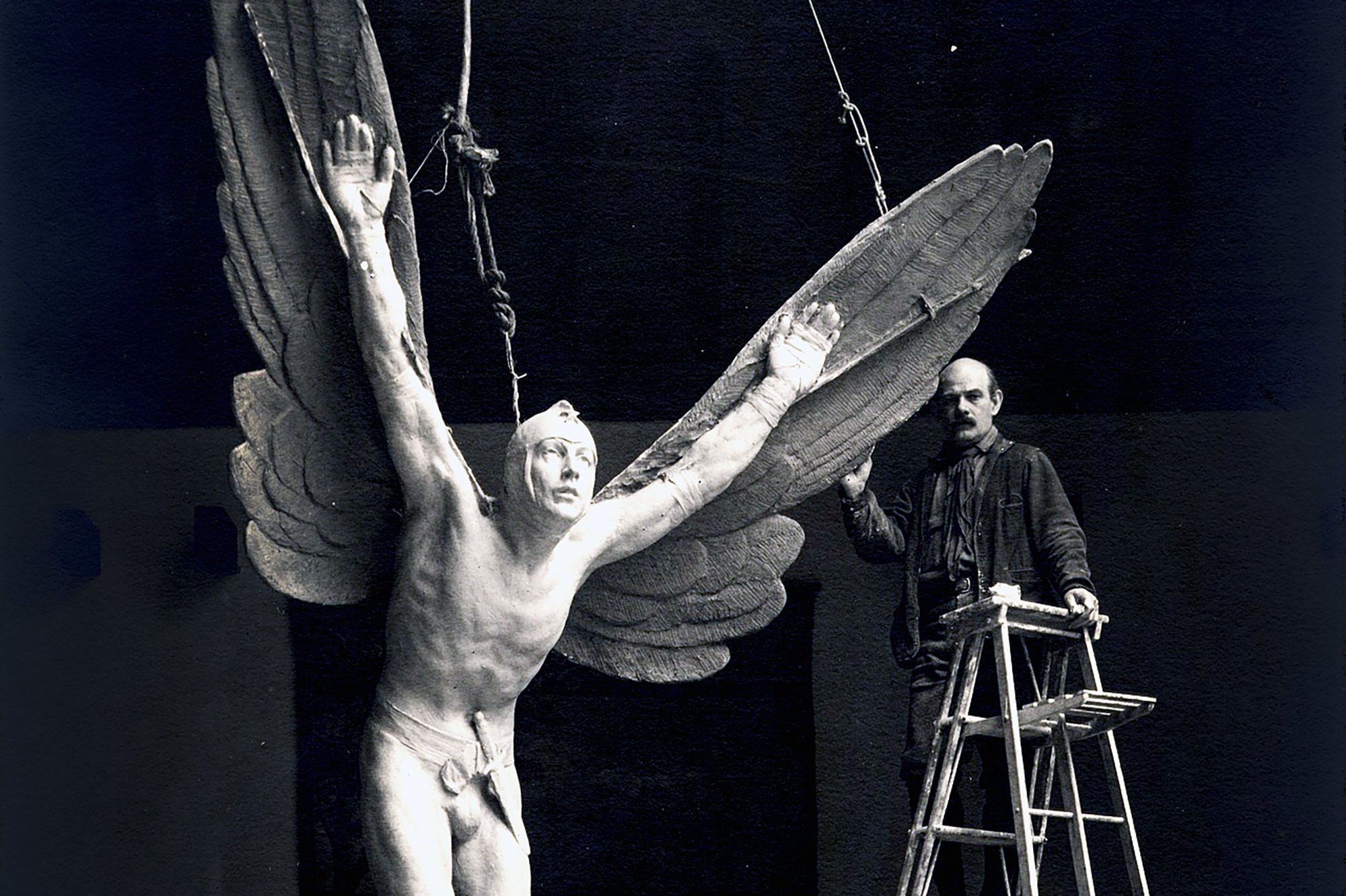

Word of McConnell’s death quickly reached UVA’s Grounds. Less than a week later, friends and fellow alumni began urging the University to erect a fitting memorial to McConnell. University President Edwin A. Alderman supported the effort and was involved throughout the process of selection, design, creation and installation of the statue. Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor of Mt. Rushmore and Stone Mountain, was commissioned. After several delays, the statue was unveiled on June 23, 1919.

“James McConnell was among the first, if not the first, student of the University to tender his services to the Allied cause in the autumn of 1914,” Alderman said in a statement issued by his office to mark the statue’s debut. “He was the first of the sons of the University to die in battle. There was a certain singular quality of heroism in the circumstances of his devotion and death that make a great appeal to the students and alumni of the institution.”

Law professor Armistead M. Dobie, who had known McConnell in law school, spoke at the dedication of “The Aviator” statue.

“To me, the most characteristic trait of Jim McConnell’s nature was a hatred of the humdrum, an abhorrence of the commonplace, a passion for the picturesque,” Dobie said. “Long before the United States had entered the war, he volunteered for service with the army of France. As dangerous and as useful as his duties were as an ambulance driver, these non-combatant tasks did not seem to him to fill the measures of his loyalty or even appear approximately to transcend the limits of his love for France.”

Dobie cited in his address that McConnell had been part of a new frontier – warfare in the air.

“Here was romance exalted to its highest level,” Dobie said. “Here, raised to the -nth power, was the picturesque. This was the individual task. Infantry fights by platoons, by companies and by larger units; artillery fights by batteries, by battalions or by greater groups; but the aviator, once launched upon his perilous flight, fights alone. For him, victory or defeat is spelled in terms of individual achievements.”

This, he said, was the lure to McConnell.

“Jim McConnell became an aviator to earn in the short space of his life still left to him (for his span of life went but a few days beyond three decades) an enviable military fame, and to win the respect and love of his associates,” Dobie said.

The statue was erected near what was then Miller Hall – now the site of the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library and the Mary and David Harrison Institute for American History, Literature, and Culture – and was later flanked by Alderman Library. When Clemons Library was built in 1981, the statue was moved onto its plaza.

“The Aviator,” which currently resides in the plaza of Clemons Library, is a tribute to James McConnell, a pilot shot down over France in World War I. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The statue has stirred controversy over the years. In 1982, it was dropped as the cover photo of the University’s telephone directory, and a Cavalier Daily editorial criticized it as an “ugly structure” and an “eyesore.” This prompted a response from then-third-year student John Jeffries and then-second-year student John Paradee, who defended the statue and McConnell. They said that friends of the flyer thought the statue was a fitting memorial.

“They remembered his ambition, his courage, and his pursuit of excellence in all endeavors,” they wrote in a letter to the student newspaper. “With these ideals in mind, they presented the University with the winged-statue bearing the inscription ‘soaring like an eagle into new heavens of valor and devotion.’ The statue is therefore not a ‘structure’ to be criticized for its artistic value, but a memorial to be appreciated for what it represents.”

The University Journal, another student newspaper (since defunct), also defended the statue in an editorial. “Aristotle believed the ‘the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance,’” the editorialists wrote. “The petty critics who have complained that the memorial to McConnell does not meet their exacting standards of artistic excellence are too blind to see real beauty. Those who are hung up on superficial appearance and are afraid to fly will never understand the statue.”

Media Contact

Article Information

March 14, 2017

/content/uva-honors-inspiration-winged-aviator-statue-100-years-after-his-death