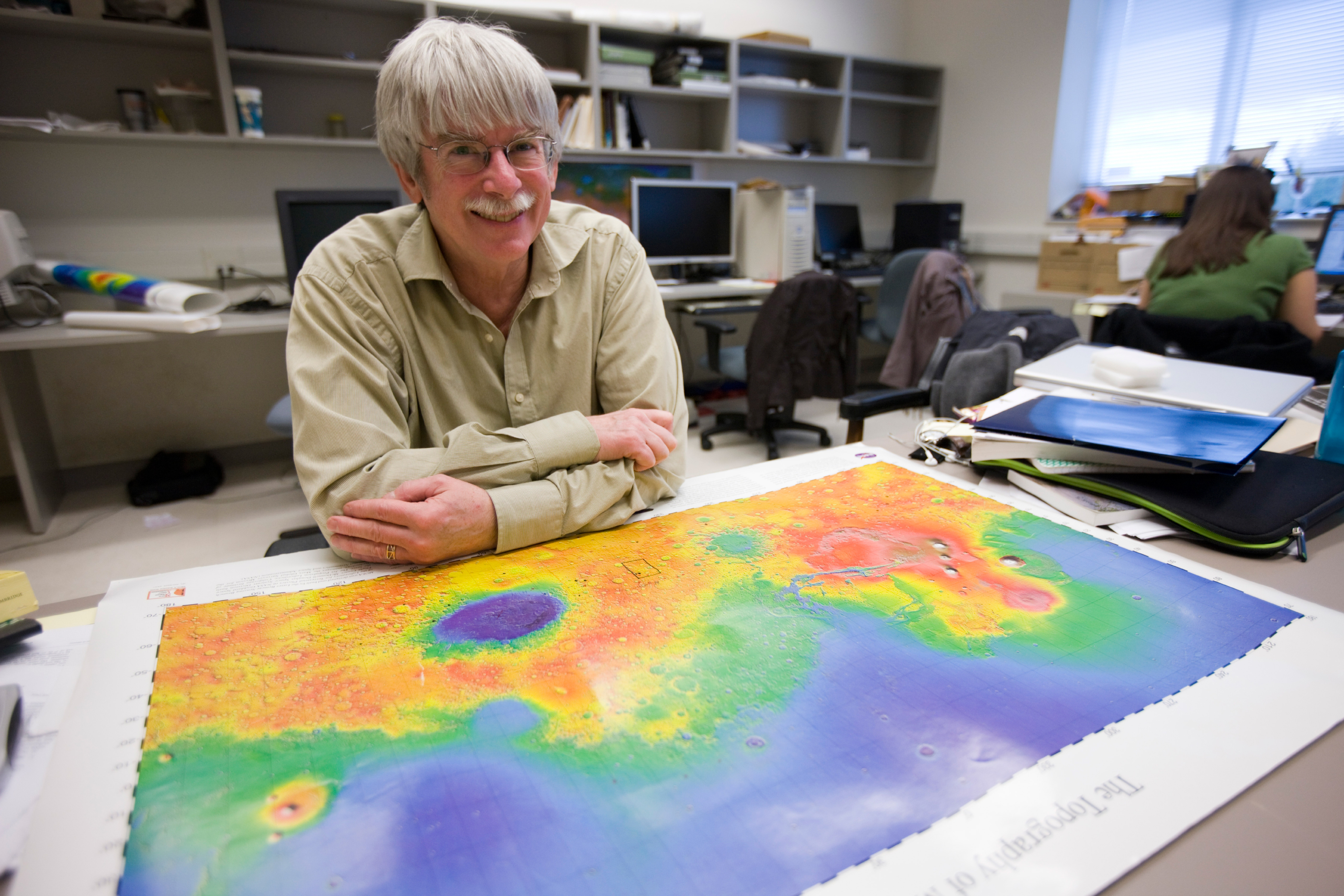

Planetary geologist Alan Howard, a University of Virginia environmental sciences professor, has made a 50-year career of comparing geological surface processes on Earth and Mars, as well as on moons of Jupiter and Saturn. He is so well-regarded that he is the only person to win all three of the most prestigious awards in his field – at least the ones awarded on this planet.

Recently the Geological Society of America presented him with its G.K. Gilbert Award for his “outstanding contributions to the solution of fundamental problems in planetary geology.”

And the American Geophysical Union will in December present Howard with its G.K. Gilbert Award for Surface Processes for his contributions to the better understanding of Earth and planetary geomorphology and for promoting “an environment of unselfish cooperation in research and the inclusion of young scientists in the field.”

That’s on top of yet another G.K. Gilbert Award, this one given to Howard in 1991 by the Association of American Geographers.

As you might guess, possibly the only better-known geologist in the particular field was G.K. Gilbert himself, one of the founders of terrestrial and planetary geomorphology, who died in 1918.

Howard is best known for studying the processes that shaped Earth, and using that to inform knowledge about the terrain of Mars – and vice versa. Like Earth, the red planet is covered with mountains, craters, ancient valleys, riverbeds and lakebeds.

Howard began studying Mars’ surface in the early 1970s, when NASA first began sending probes and receiving detailed imagery of its surface. As details have emerged with increasingly higher resolution, Howard and his colleagues have pieced together what they believe is a timeline of surface activity on the planet, much of it shaped by water that once was abundant and flowing there.

“The issue is whether or not life could have evolved on Mars,” Howard said. “We can use Earth as an analogue, seeking clues here that may apply to Mars. Likewise, what we learn from Mars can tell us some things about surface geology on Earth.”

It’s the water that makes Mars so fascinating to scientists. It likely is the only planet in the solar system, other than Earth (and possibly those moons of Saturn and Jupiter), that may have provided habitability for life at some points in its history – and possibly even presently in moisture under rocks (though any organic matter likely would be bacteria).

Howard is working to understand the sequence of events in Mars’ history that would indicate if and when life might have occurred based on atmospheric and surface conditions. He likewise can apply that to how things may have occurred early in the Earth’s history, when its surface, climate and atmosphere probably were much like that of Mars.

His findings suggest that early Mars was relatively warm and wet. He and his colleagues have shown that after an era of heavy bombardment of Mars by meteors, the planet experienced widespread and intense river flow activity that dissected the cratered highlands. A few hundred million years later, large alluvial fans formed on crater walls and shallow valleys, developed from snow melt, much as occurs on Earth.

Howard knows that episodic flooding created erosion and the sort of alluvial fans also found on Earth where rivers tail out into deltas. But his Mars findings have revealed that there are some gaps in knowledge regarding the way alluvial fans form on Earth.

In recent years, he has taken his investigations of the red planet and applied them to particular places on Earth where the surface terrain is remarkably similar, such as the ancient alluvial fans of the Atacama Desert in Chile and the meandering channel beds in the Nevada desert. Both sites allow him to study water flow patterns and precipitation cycles.

The area of Nevada he investigates is in the remote Blackrock Desert Wilderness Area, and requires Howard and his students to pack in on horseback all their food, equipment, supplies and instruments.

“It’s just like prospecting in the days of the Old West,” he said.

But the gold is, in effect, on the red planet.

Media Contact

Article Information

November 20, 2013

/content/uva-s-howard-awarded-top-geomorphology-awards-planetary-comparison-research