Former President Jimmy Carter spent only four years in office, but his public service and affiliation with the University of Virginia lasted for decades.

Carter was 100 years old when he died Dec. 29, making him the longest-lived United States president. He spent 22 months in hospice care. His wife, Rosalynn, joined him in hospice care in November 2023 and died a few days later. The former president attended her funeral reclined in a wheelchair.

Carter, who beat Republican opponent and incumbent President Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential election, made several appearances at UVA after his tumultuous term in office, including a 1991 presentation and dinner with Dillard Scholars in the UVA School of Law – a dinner that included then-student Jim Ryan, now UVA’s president.

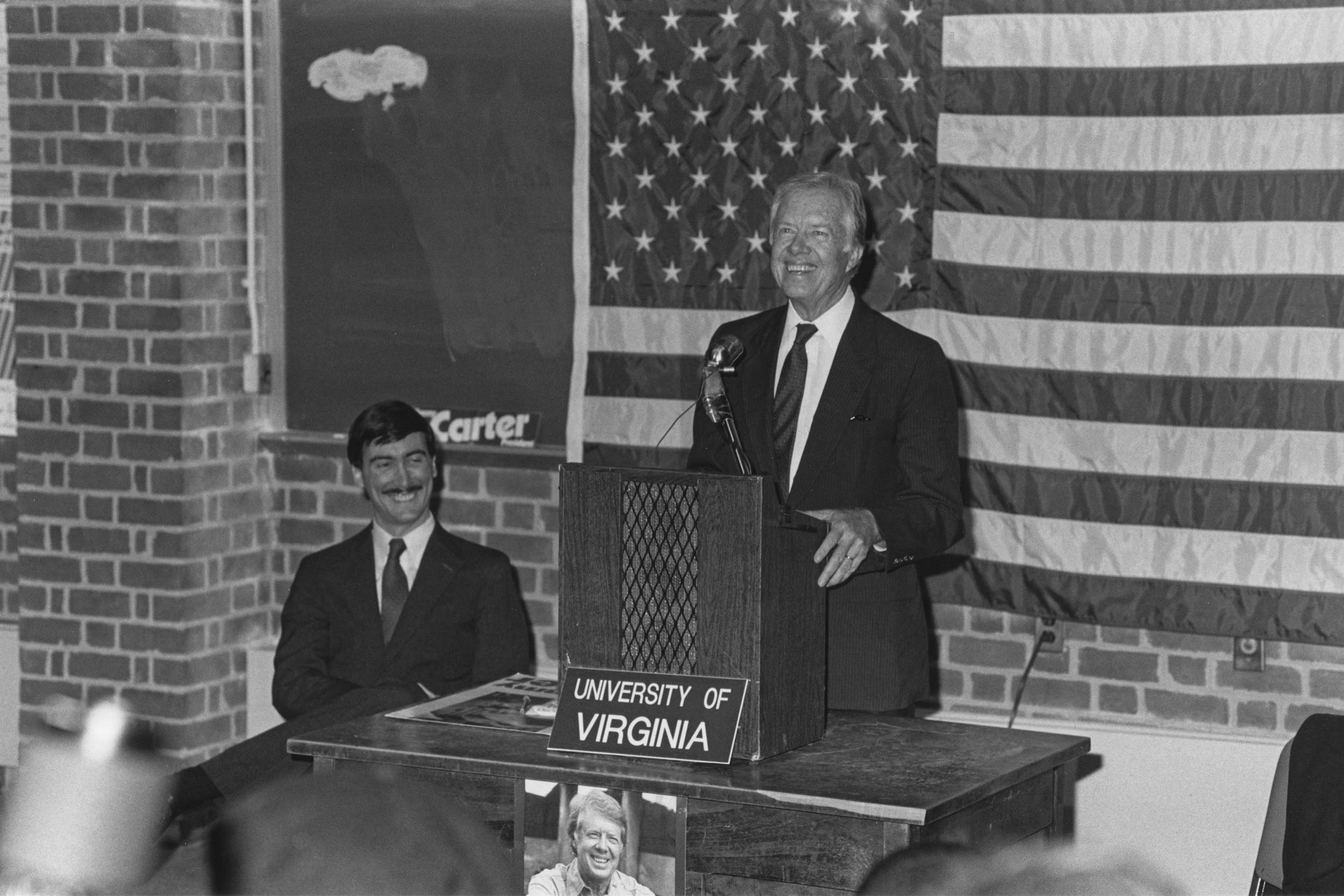

Former President Jimmy Carter gave the Dillard Scholars Lecture at the UVA School of Law in April 1991 and afterward had dinner with Dillard Scholars, including then-student and now UVA President Jim Ryan. (Contributed photo)

Larry Sabato, director of the UVA Center for politics, recalled another memorable visit. “Carter came to my Introduction to American Politics class in 1986,” Sabato said. “Wilson Auditorium was filled to the rooftop with hundreds of students who went bananas when he walked in. It was the kind of rapturous reception that had become rare for Carter, and he never forgot it. Every time I talked to him after that, he mentioned the class first thing.”

Carter also worked with University experts on a successful election reform law in the wake of the disputed 2000 presidential election.

“I began working with former President Carter as the Miller Center revived its work on oral history, in which Carter had played a constructive part,” said Philip Zelikow, the White Burkett Miller Professor of History at UVA. “But he really stepped up after the terrible controversy over the counting of ballots in Florida in the 2000 presidential election.”

Zelikow, who served as the executive director of the 9/11 Commission, was serving as the Miller Center’s director when the results of the 2000 presidential election between Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Al Gore came down to contentious recount in Florida, sparking a divisive national controversy that ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Carter joined with Ford to co-chair the 2001 National Commission on Federal Election Reform and asked Zelikow to direct the effort through the Miller Center. Carter led the effort after Ford’s health forced his withdrawal.

“Drawing from his experience with voting problems and civil rights in Georgia and his experience with modernizing voting systems around the world, Carter brought real insight and a determination to listen to concerns from all sides,” Zelikow said. “The press assumed our commission would fail because the election administration issues were so partisan and bitter. Sound familiar?”

A marathon meeting schedule in Charlottesville, on Grounds and at the Miller Center with the commission, chaired by the then 76-year-old Carter, resulted in a report that led to the Help America Vote Act, signed into law in October 2002.

Carter and former president Gerald Ford co-chaired the National Commission on Federal Election Reform in response to the ballot-counting controversy of the 2000 presidential contest. He drew on his experience with voting and civil rights in Georgia to help create legislation. (Photo by Matt Kelly, University Communications)

“It was, Congressman John Lewis explained, the most important election legislation since the Voting Rights Act. It modernized election systems. It set national standards of performance. It mandated statewide voting lists,” Zelikow said. “It created the system of provisional ballots and much more. In other words, the act shored up the election system just enough to survive the test it would face in 2020.”

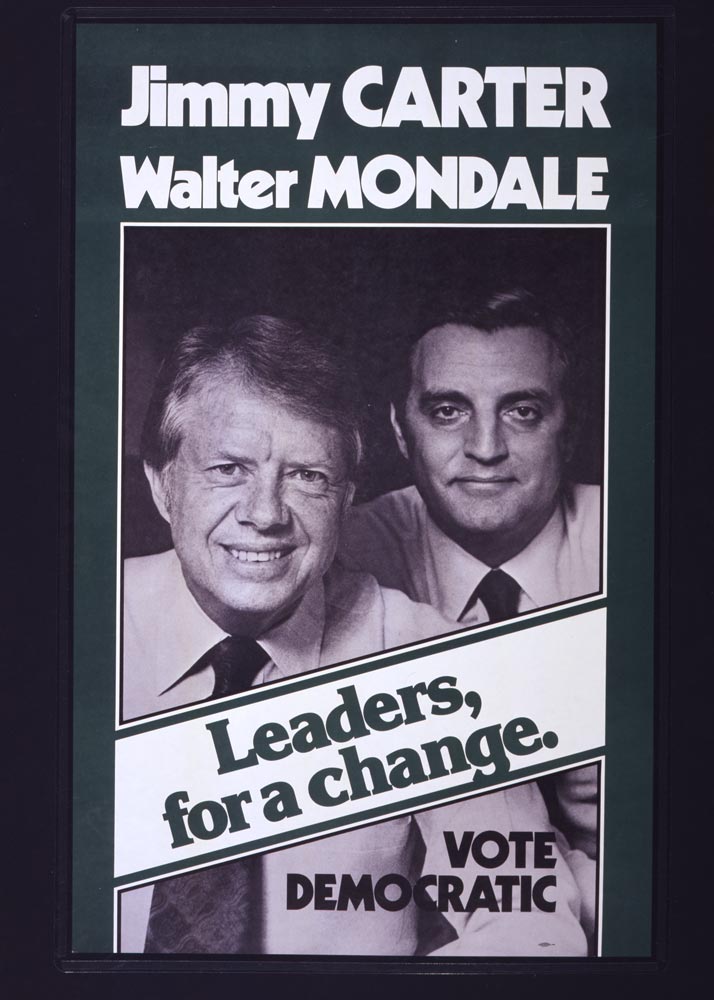

Carter was a little-known Georgia governor and peanut farmer when he rose to the top of the Democratic presidential ticket for the 1976 election.

“That’s always been very meaningful to me as a political scientist, to think that people didn’t know him, and that was the very thing that helped him win,” said Barbara A. Perry, the J. Wilson Newman Professor of Governance in presidential studies at the Miller Center. Perry is also the co-chair of the center’s Presidential Oral History Program. “People were sick of Washington. They were sick of Watergate, and sick of Richard Nixon, and the Ford pardon of Nixon, and Vietnam.”

A poster from the 1976 campaign for U.S. president featured eventual winner Jimmy Carter and Vice President Walter F. Mondale. (Library of Congress)

Perry saw Carter’s rise firsthand when she served as a page at a Democratic National Committee meeting as a high school senior in 1973. She was at the party’s 1975 issues conference among top candidates, where Carter proved he had a grasp of foreign policy.

“This populist, who carried his own luggage was a man of the people and a born-again Christian who didn’t try to hide his religion, made a splash,” Perry said. “The irony to me is, those very things turned out to be handicaps in the presidency.”

Carter’s term proved a rough road. Although he mediated a peace agreement between Egypt and Israel in the Camp David Accords – one that still holds today – he was less effective at dealing with “stagflation” and an oil crisis. In 1979, Iranian militants stormed the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, taking American hostages. An April 1980 mission to rescue the hostages failed, resulting in the deaths of eight U.S. servicemen.

Carter lost the November ballot to Republican Ronald Reagan, and embarked upon what many have described as the most successful post-presidential career in U.S. history. He began serving with Habitat for Humanity and working internationally to improve housing and medical care and promote democracy.

His strongest UVA connections came after he left office.

“In my view, Carter was a better president than has been acknowledged,” Sabato said. “Carter had bad luck more than anything else, in the economy and foreign policy.”

Perry agreed.

“There is a quote often attributed to golfer Lee Trevino that ‘The harder I work, the luckier I seem to get,’” she said. “In some ways, Carter’s presidency demonstrated the polar opposite of that: The harder he worked, the unluckier he seemed to get.”