Nelson said he hopes the book will fill in a “huge gap” in UVA history. Difficult though it may be, telling the full story is necessary for the University, he said, “to press through the historical reality so we can become the university we want to be, to model our responsibility and move with integrity toward a robust democracy.”

He mentioned that the Bicentennial Commission helped to fund one effort to share this history: starting last week, copies of “Educated in Tyranny” were being shipped to every public high school in Virginia.

On Thursday, a public talk with McInnis and Nelson, plus UVA President Jim Ryan will be held in the Rotunda Dome Room from 1 to 2 p.m. to mark the book’s publication.

Here are just a few of the insights and examples culled from various chapters of the new book.

1. Jefferson wrote about believing a Southern college was needed “to protect the sons of the South from the abolitionist teachings in the North.” Nevertheless, he also described the ‘unremitting despotism,’ of slavery and noted how ‘[t]he parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to his worst of passions, and thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious peculiarities.” This quote, taken from Jefferson’s “Notes on the State of Virginia,” inspired the book’s title.

2. In some ways, the duties of enslaved laborers to grow, prepare and serve food, provide firewood, tend livestock, make bricks and build buildings made life in the University’s early days seem like a plantation.

3. In other ways, the Academical Village was similar to a village or town, because of the number of buildings, separate households and people packed close together and engaged in many activities.

Sometimes, this gave enslaved workers – who were owned by hotelkeepers or faculty members, or rented from elsewhere – more mobility than in other situations.

4. Enslaved workers were subjected to the whims of many different white people, not just whoever owned them. Although they were not allowed to bring enslaved laborers with them, the white male students acted as if they were masters and often mistreated the workers, even children, violently and with impunity.

In one case from 1856, a student severely beat a 10-year-old enslaved girl who worked at a nearby boarding house, and said in his testimony before the faculty that he did so because she had spoken to him with impertinence. The faculty were going to expel him until he apologized – to the person who owned the girl. The student also said his actions could “be defended on the ground of the necessity of maintaining the due subordination in this class of persons.”

5. Some enslaved workers were able to do errands for students and earn a little of their own money. The faculty didn’t approve of this practice because the errands would often involve buying alcohol or illicit activities.

6. Enslaved laborers who became highly skilled and known for their expertise were at higher risk if they attempted escape, because there was more impetus and information to track them down and capture them.

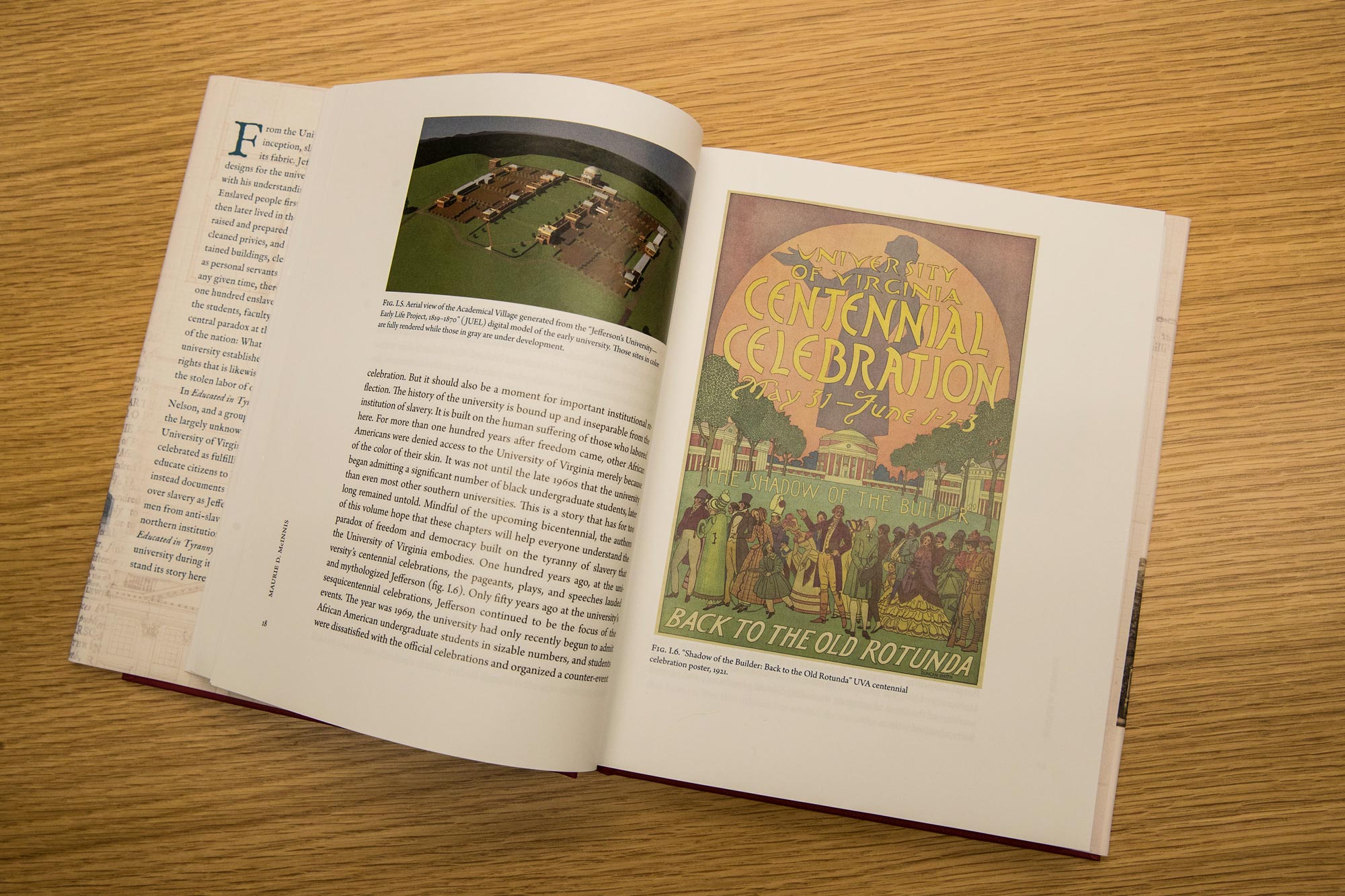

7. Jefferson’s architectural designs for the Academical Village attempted to keep the activities of enslavement hidden, but he didn’t provide enough space for their living accommodations. The Lawn masks the labor that happened behind the façades of buildings, and today’s gardens behind the pavilions were originally workyards where enslaved laborers worked.

“[Jefferson] determined how best to mask slavery by creating separate public, private, and enslaved zones in buildings and landscapes,” Nelson and McInnis write in a chapter on the landscape of slavery.

8. The hotel kitchens were built in dank cellars and it’s unclear how many people would have to sleep there or in an adjacent room underground, but hotelkeepers and faculty complained that the living quarters were so unhealthy, it was making the enslaved laborers ill.

9. “The education that students at the University of Virginia received consistently reinforced the values of a slave society, both in the formal curriculum and in the students’ activities outside of the classroom, where they constantly encountered proslavery rhetoric in speech, debate, and writing,” according to an essay by Thomas Howard and Alfred Brophy. Howard, a UVA alumnus, and Brophy, a University of Alabama scholar of antebellum jurisprudence, discuss the prevalence of proslavery ideas in the chapter on “Proslavery Thought.” Most of the faculty leaned heavily in favor of slavery – this is apparent repeatedly in many different examples, they explain.

10. Jefferson included medical education at the new university and designed the Anatomical Theater for dissecting cadavers; mostly African American corpses were used. In a chapter about the Anatomical Theater, Von Daacke describes a grisly business of stealing bodies and selling them to schools teaching anatomy. Even after an 1848 law made grave-robbing criminal, it did not stem the competition for cadavers at UVA and two other schools in the state, Winchester Medical College and Hampden-Sydney’s medical school which became the Medical College of Virginia. The theft of black bodies was overlooked for the most part.

Located about where the Berlin Wall section is displayed near Alderman Library, the Anatomical Theater is the only Jefferson-designed building that has been torn down. That occurred in 1939; after the hospital was established in 1901, it fell into disuse.

Von Daacke concludes, “Jefferson’s interest in scientifically proving white supremacy and black difference, James Lawrence Cabell’s similar desires and the expansion of race science-based medical training at the university, and decades of black cadaver dissections set the stage for the rise of eugenics at the school in the early 20th century.”