With the 50th anniversary of the National Endowment for the Humanities approaching, one might be surprised by the continuing debate over the humanities’ relevance in higher education. One camp argues they are foundational to a rounded education; another says professional degrees should fill the menu.

Chad Wellmon described Nietzsche’s lectures on the state of German higher education as not optimistic, but it “diagnostically revelatory.”

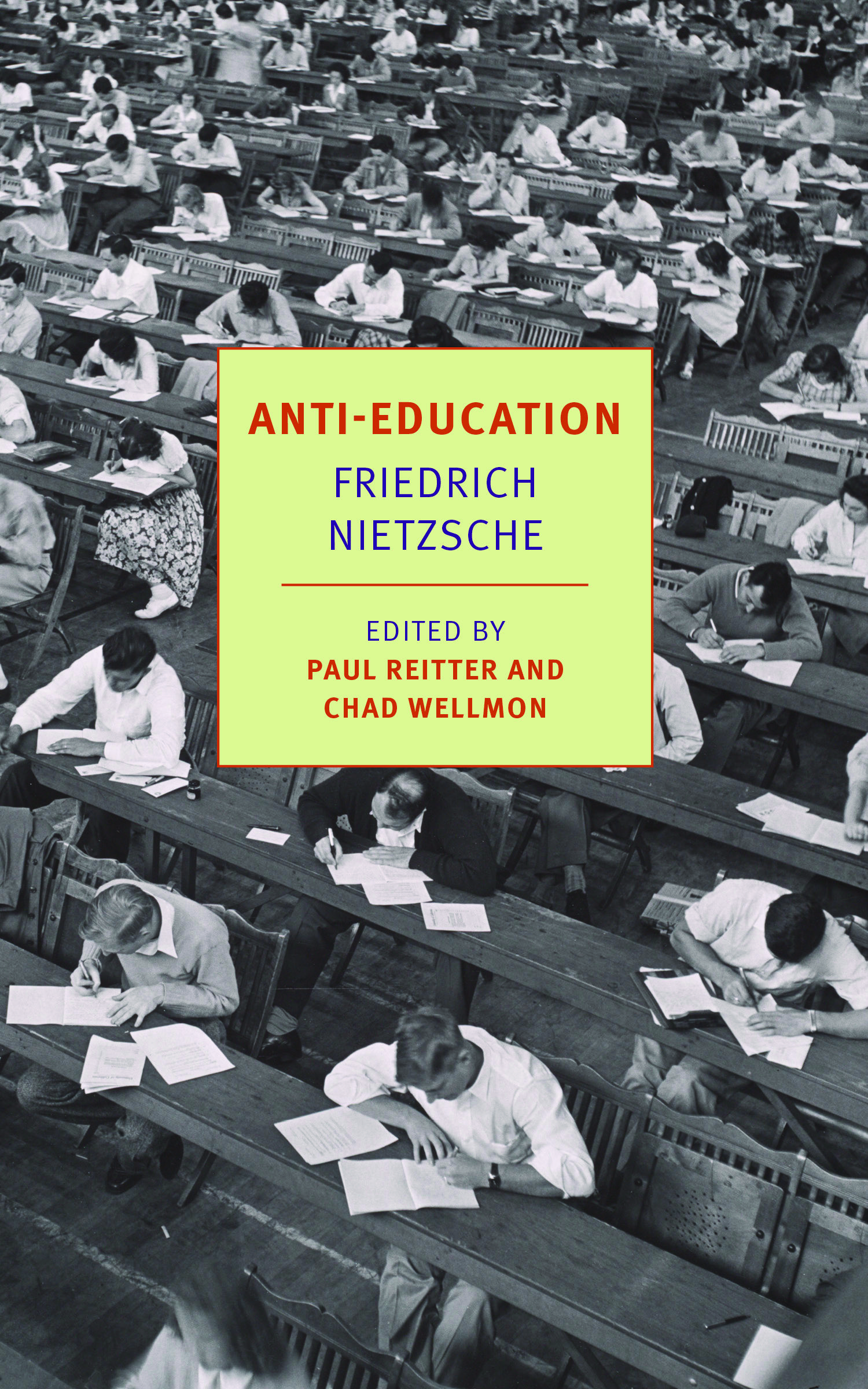

Chad Wellmon, an associate professor of Germanic languages and literatures and a faculty fellow in the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia, co-edited the book and wrote an introduction and notes with Ohio State colleague Paul Reitter. The translator is Damion Searls. Wellmon, author most recently of “Organizing Enlightenment: Information Overload and the Invention of the Modern Research University,” talked with UVA Today about the relevance of Nietzsche’s heretofore largely unknown lectures.

Q. How would you describe the lectures?

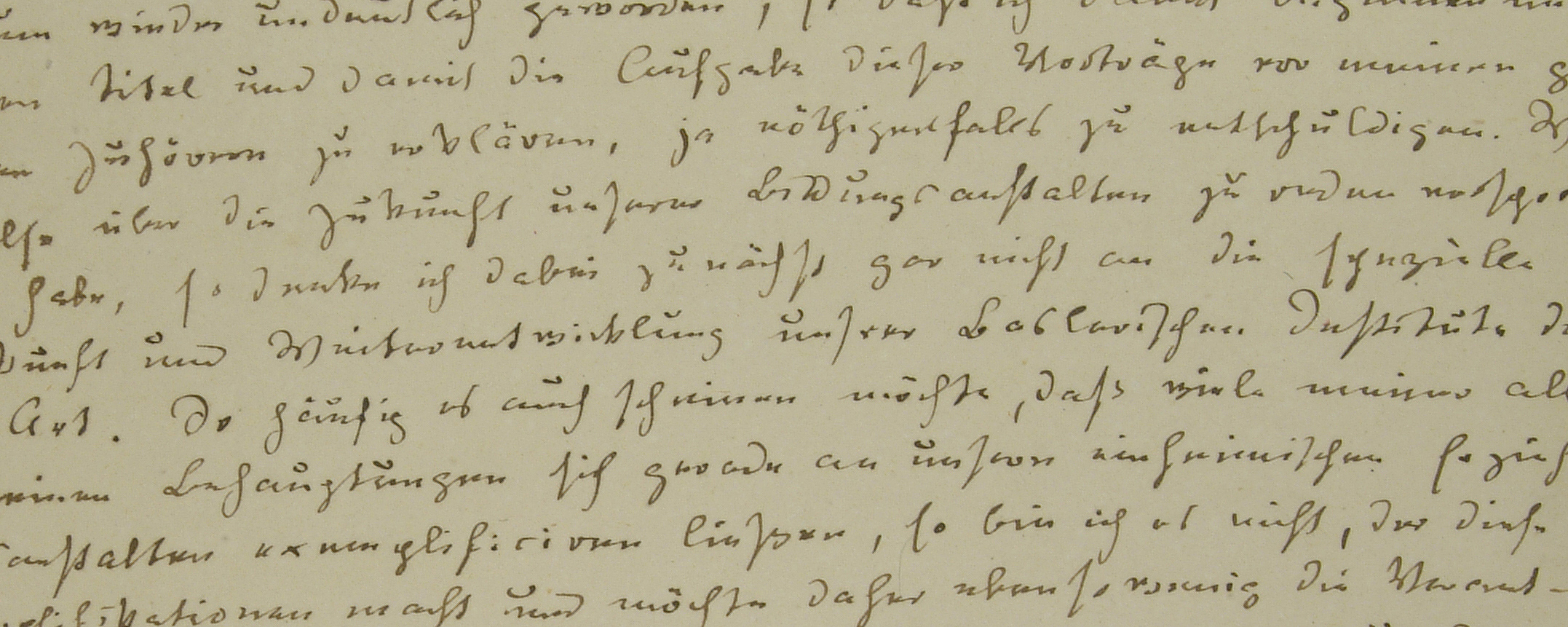

A. In the winter of 1872, Nietzsche delivered these lectures not at the university, but in the city museum, where over a series of five nights hundreds of citizens, not just academics, crowded in to hear this young classics professor excoriate German universities and culture more broadly.

They were about the sad state of the humanities and the bleak future of German educational and cultural institutions. In a way, they were one of his first direct attacks on the myopia and waywardness of the academy. Even though Nietzsche didn’t resign until several years after he gave the lectures, they read as an early form of “quit lit,” that now-ubiquitous genre in which faculty members feel compelled to write about why they’re leaving academia and the overwhelming angst it’s causing them.

But Nietzsche being Nietzsche, his version of “quit lit” lacks the self-pitying angst and is full of incisive criticisms of institutions that he thinks have lost their bearings. And they’re just funny.

The lectures are actually in the form of an extended dialogue between two German frat boys who had gone off into a forest to shoot their guns. While setting up their targets and reminiscing about when they used to read poetry, they happen upon a cantankerous old philosopher, his younger companion and their dog. Through these characters, Nietzsche criticizes what has become of high school and university education.

He says that society is putting too much emphasis on skills training so that people can go out and make money and devote themselves to the state; he argues that professors were no longer capable of asking big questions, so they focus on ever-more-specialized minutia; he suggests that democracy might not be compatible with humanistic inquiry; he mocks the overly subjective focus of education – discover who you are! – and insists that education is about discipline and recognizing what is truly good and valuable; he wonders what can become of education when its only end is economic utility.

He hits these themes over and over again. It’s one long lament over five lectures of the loss of culture at the hands of democratization, industrialization and modernity more generally. It’s brutal.

Q: How did Schopenhauer and Wagner influence Nietzsche?

A. Nietzsche writes in his letters and his diaries that he felt fully liberated when he read Schopenhauer because he wasn’t just some dry, academic philosopher. The effect would be like reading an acerbic, cultural critic of today, like David Carr (a former New York Times media columnist who died in February) or Thomas Frank of The Baffler, a periodical the motto of which is “the journal that blunts the cutting edge.”

Wagner represented the embodiment of that cultural genius, whose greatness, thought the young Nietzsche, could lift Germany out of its cultural malaise and break it free from its stultifying institutions, and its drab democratic commitments which were obsessed with making everyone equal and thus – Nietzsche’s argument – the same.

For Nietzsche, at the heart of the humanistic tradition, and the humanities more broadly, was a deeply un-democractic, anti-egalitarian strand. This was, for him, a fact that his fellow scholars and contemporaries refused to acknowledge. In democratizing the humanities, they were actually destroying them. To say the least, that’s not a comforting or acceptable notion today and it wasn’t very popular in late 19th-century Germany either.

Q. Why did you decide to translate these lectures?

A. Nietzsche’s critiques of the university and of the crisis of the humanities anticipate the arguments that you hear made today on either side of the debates about higher education. The parallels are striking and sobering.

There is this great passage where he mocks German university professors for relying on lecturing. University students, he says, are connected to the university by their ear. They just listen to their professors boringly read their latest academic tome to students. Why would anyone pay for that when you can buy the book? It’s an absurd proposition.

There is another passage in which he mocks journalists’ attempts to answer big questions and think in public. But, he says, you can’t really blame them for their pitiful attempts. Professors had given up on thinking big and beyond their highly specialized work, much less talking to anyone outside their tiny guild. So, journalists saw an opportunity and took it. And now all of us suffer.

He doesn’t offer any solutions to the perceived crisis. In fact, the lectures are pretty bleak, and ultimately Nietzsche leaves the university. Soon after the lectures, he begins to write the material for which he became famous, like “Beyond Good and Evil.” He becomes increasingly aphoristic, but the themes of his future work – his critique of modernity, democracy, the liberal subject, subjectivity – are all here.

Ultimately, I think the lectures raise a host of profound, even troubling questions, both historically and today. And one of those is the assumption that the humanities are necessarily humanizing and democratic. Nietzsche’s point is simply that they aren’t necessarily anything. They can and have been put to a whole host of ends – good and bad.

Q. What do you imagine it must have been like to be in the audience when these lectures where given in the winter of 1872?

A. It must have been all a bit bewildering and inspiring, because you’re listening to these in a museum and you have this young classics professor presenting a dialogue about how bad our cultural institutions are between some frat boys and a crotchety old philosopher – I mean, he’s repulsive at points. And then, just when you thought some comic relief might come in, the younger companion exclaims how the cultural situation is even worse than we thought. And despite all that, there is an energy and optimism in human creativity that suffuses the entire series of lectures.

For me, it would have incited this capacious vision of a culture in chaos. I would imagine that when you walk out of there, you hear and see everything that Nietzsche was talking about. It was bombastic and pessimistic, but it was diagnostically revelatory.

The lectures were provocative in the sense that they so clearly anticipated an entire critique of modernity and its institutions. But nowhere do they, unlike some of the critiques to come, offer easy solutions or even the suggestion that in some mythic golden age it was all better. I find that oddly comforting.

You can read an excerpt from the lectures published here in Harpers September ‘readings’ section. “Anti-Education” is published by New York Review Books and goes on sale Nov. 24.

Media Contact

Article Information

November 6, 2015

/content/143-years-ago-nietzsche-presaged-modern-debate-relevance-humanities