After covering a Super Bowl, the Atlanta Summer Olympics, five Final Fours and unearthing countless untold stories from the world of professional wrestling, University of Virginia alumnus John Hollis wondered if his life as a writer could possibly get more interesting.

That’s when Hollis started researching the life of his wife’s late uncle.

Many people knew U.S. Marine Sgt. Rodney M. Davis as an African-American soldier who threw himself on top of an enemy grenade to save the lives of five fellow Marines in Vietnam in 1967.

What virtually nobody knew – even Davis’ family members – was that all of the Marines Davis saved were white.

“It was a big deal because in 1967, more than 100 American cities had race riots,” Hollis said. “Sgt. Davis’ hometown of Macon [Georgia] was still under the boot of Jim Crow, which means that those same Marines that he fought and died for – who were his brothers in every sense of the word – he couldn’t eat in the same restaurants with them back in his own hometown. But he did what he did anyway because he loved his country and he loved his fellow Marines.”

Hollis’ discovery made one for one heck of a book.

Published in 2018, “Sgt. Rodney M. Davis: The Making of a Hero” explores why Davis – who had a wife and two infant children at home – “did what he did.”

“It was one of the most riveting stories I’ve ever encountered,” Hollis said.

As part of Black History Month in February, Hollis wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post about what the Davis story can tell America about race.

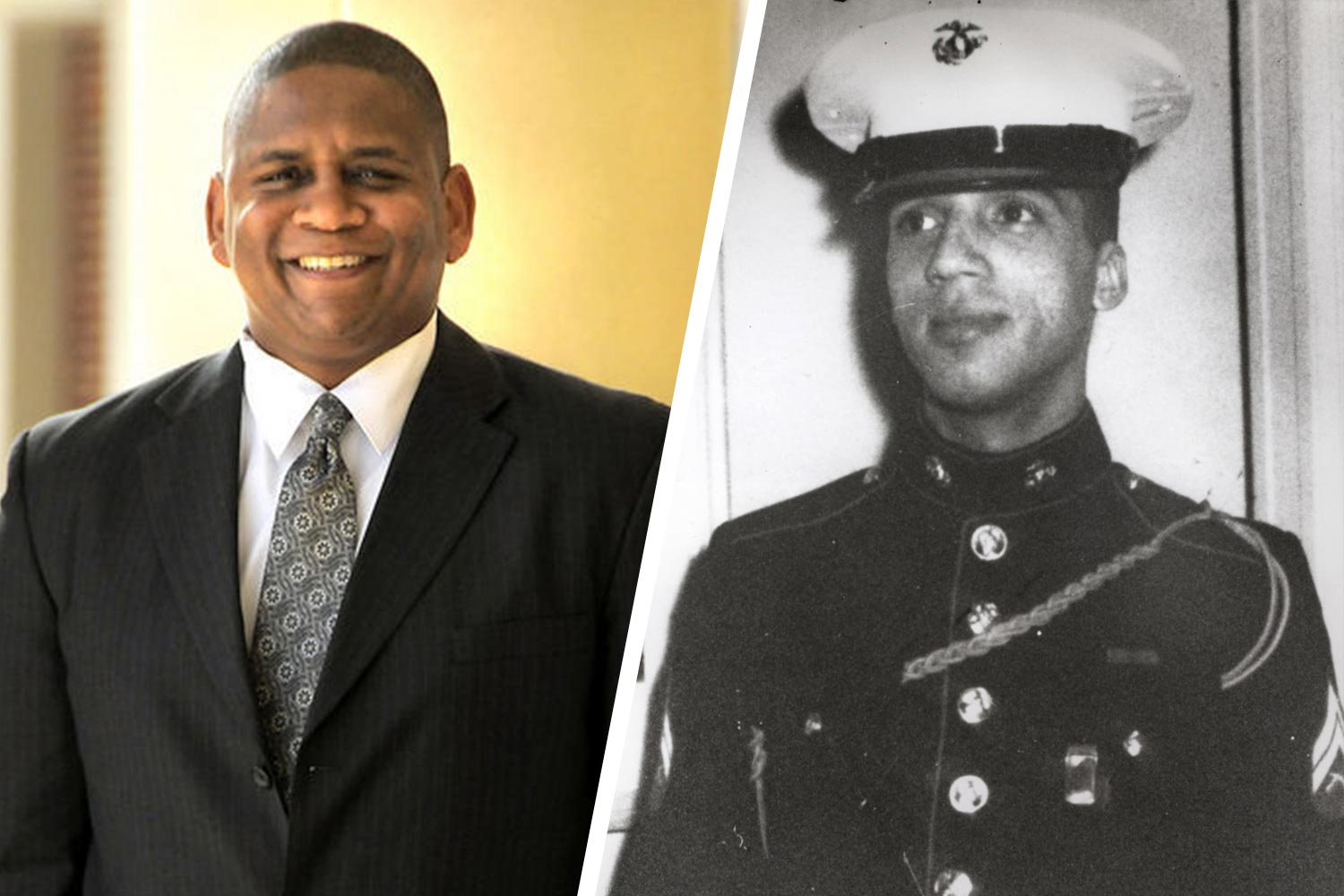

UVA alumnus John Hollis was a sportswriter for many years prior to writing books. (Contributed photo)

Hollis, who grew up in Fredericksburg, said he’s always had natural writing ability, honing it first at Woodberry Forest School and later at UVA, where he remembers writing lengthy papers on Watergate and the Bay of Pigs invasion as a foreign affairs major. “That just whetted my appetite,” Hollis said. “I loved the research part of it and finding out about so many things I didn’t know.”

After graduating, Hollis spent many years as a sportswriter at newspapers in Virginia; Gainesville, Florida; and Atlanta.

“There was no one on staff – or at competing papers, as far as I could tell – who matched the enthusiasm for their job and for sports that John had,” said Jon DeNunzio, who worked with Hollis at the Potomac News in Woodbridge from 1992 to ’94. “Additionally, he always knew exactly what was going on on his beats. I assume that came from hard work and his outgoing, affable nature. What source would turn down a call from John Hollis?”

Hollis covered the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta for the News, following a pair of Northern Virginia athletes who were competing.

Frighteningly, Hollis was in Atlanta’s Centennial Park, hanging out with a group of UVA friends, when a terrorist’s bomb exploded, killing two people and injuring more than 100. Eric Rudolph was later convicted and sentenced to multiple life terms for that attack and a series of others.

“It was one of the best stories I ever wrote because I just so happened to be one of the only reporters who was actually there the moment it happened,” Hollis said. “The crazy part is we had walked right in that spot where the bomb went off maybe 20 minutes earlier. By the grace of God, we survived.”

Hollis worked briefly at CNN, then went on to take a job for the Gainesville (Florida) Sun, where he served as the beat writer covering the University of Florida men’s basketball team. Hollis, who also covered Gator football and other sports, was on the beat for the Gators’ run to the 2000 Final Four in Indianapolis.

From there, Hollis moved on to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, where he covered a wide range of sports before settling in as the Georgia Tech beat writer and covering the Yellow Jacket men’s basketball team when it reached the 2004 Final Four in San Antonio.

Toward the end of his time at the paper, Hollis decided to explore subjects outside of sports and took a reporting job on the metro desk.

However, he was soon reeled back in after a shocking tragedy involving former pro wrestler Chris Benoit, an Atlanta resident who killed his wife and son before taking his own life. Hollis became the paper’s de facto wrestling writer, authoring a series of stories that exposed the underbelly of professional wrestling.

They were devoured by readers.

“Pro wrestling cuts across every demographic – black-white, rich-poor, young-old,” Hollis said. “It was really frightening, actually.”

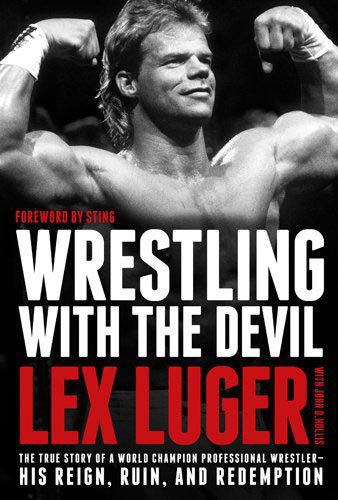

Hollis became good friends with wrestling legend Lex Luger. (Contributed photo)

One of Hollis’ most popular pieces was on legendary wrestler Lex Luger.

“I’ve never in my life had that many phone calls and emails from one story,” Hollis recalled. “I had covered Super Bowls and Olympics and Final Fours and all this stuff, but nothing generated as much response as that story.”

Two years later, while still working at the Journal-Constitution, Hollis got a call out of nowhere from Luger, who wanted to do a book.

“It was like, ‘Of course!’ I’m not going to say no to ‘The Total Package,’” said Hollis, with a hearty laugh, referring to Luger’s in-ring moniker.

In 2013, “Wrestling with the Devil: The True Story of a World Champion Professional Wrestler – His Reign, Ruin and Redemption” was published, chronicling Luger’s behind-the-scenes struggle with addiction and, later, his fight for survival and redemption.

“I heard all the details of all these stories. … It was so incredible,” Hollis said. “And he became a really good friend.”

After the Luger book, Hollis – who’s always had a love for American history (his mother was a high school history teacher) – turned his attention to Davis, his wife’s uncle who had been posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor during the Vietnam War.

Hollis interviewed more than 50 Marines who fought with Davis, including three of the five Marines who were saved by Davis’ selfless act.

“It was clear that the Sergeant Davis story captivated John from the outset," said Richard Gable, a UVA alumnus who has known Hollis since they lived in Maupin House as first-year students. "The opportunity to research the story of a true American hero who also happened to be a close relative and tell it through the lens of the racial tensions of the late 1960s was just the perfect combination for him as an author.”

Marine Sgt. Rodney M. Davis threw himself on top of an enemy grenade to save the lives of five fellow Marines in Vietnam in 1967. (Contributed photo)

Hollis still has trouble wrapping his head around what Davis did.

“It makes you wonder what you would do in that situation,” he said. “And there’s no right or wrong answer. Nobody would ever know until you’re in that situation. He was married with a 1- and 2-year-old daughter and still did what he did.

“There’s not a day that goes by where I don’t wonder what I would do in that situation. You’d like to think you’d be courageous and noble. We all think that. But I couldn’t fault anybody for doing otherwise, either.”

In June, Hollis – who has a 14-year-old son – wrote a heartfelt piece for Father’s Day about his experience as a father for the New York Daily News.

Up next for Hollis – who since 2017 has served as the communications manager at George Mason University and has also worked for the Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl – is a book on an attempted jailbreak from a federal maximum-security prison in New York City that took place in 1981.

Hollis is excited about the project.

“You never know where the research is going to take you,” he said. “That was the case with the Sergeant Davis story. When I went into it, I, too, assumed that some of the Marines in that trench with him were white. It wasn’t until doing the research that I found out all of them were. It changed the whole dynamic of the story, just like that.

“That’s what I love about research. You never know where it’s going to take you. I tell kids all the time, you don’t go into a project with a pre-assumed mindset because you just never know what you might find.”

Media Contact

Article Information

July 30, 2019

/content/alum-chronicles-marines-ultimate-sacrifice-vietnam-other-powerful-stories