In 1916, at age 38, Scotsman Muirhead Bone was drafted into the British Army not as a foot soldier, but as the first of many “war artists.”

His orders? Create work that would inspire citizens to contribute to the war effort and motivate neutral nations to join in.

One hundred years after Bone was enlisted, his images – and those of several other war artists – are on display in The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia. The newly opened exhibition, “THE GREAT WAR: Printmakers of World War I from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts,” will run through Dec. 18.

Depicting battlefields and factories, soldiers and civilians, the drawings illustrate the grim might of a war effort unlike anything the world had seen before. They were part historical documentation and part propaganda, as Britain tried to convince the United States and other neutral nations to join its fight against the Central Powers.

“These works were supposed to instill pride and confidence in the public and show the greatness of industry,” said Stephen Margulies, a volunteer curator at The Fralin. “But the dark, heavy aspect of a war driven by massive industry is also expressed.”

The British War Propaganda Bureau formally established its Official War Artists initiative in May 1916, with Bone as the first recruit. Others followed, mostly artists and architects who had built established careers before the war. They dispersed across the battlefields of Europe, hovering just behind the front lines to create drawings that were printed and published in newspapers worldwide. Several were printed as portfolios or sets of etchings, which were presented as art exhibitions in England or the United States.

“Photography was beginning to appear in newspapers, but most were still hiring artists to do the work of photographers, or even work that smartphones would do today,” Margulies said. “In some ways, I believe these artists got closer to the reality of war than photography could. The prints were drawn by human hands and I think they express things that are missed by photographic imagery.”

Below, UVA Today previews a few works from ”THE GREAT WAR” exhibition, each with its own unique backstory.

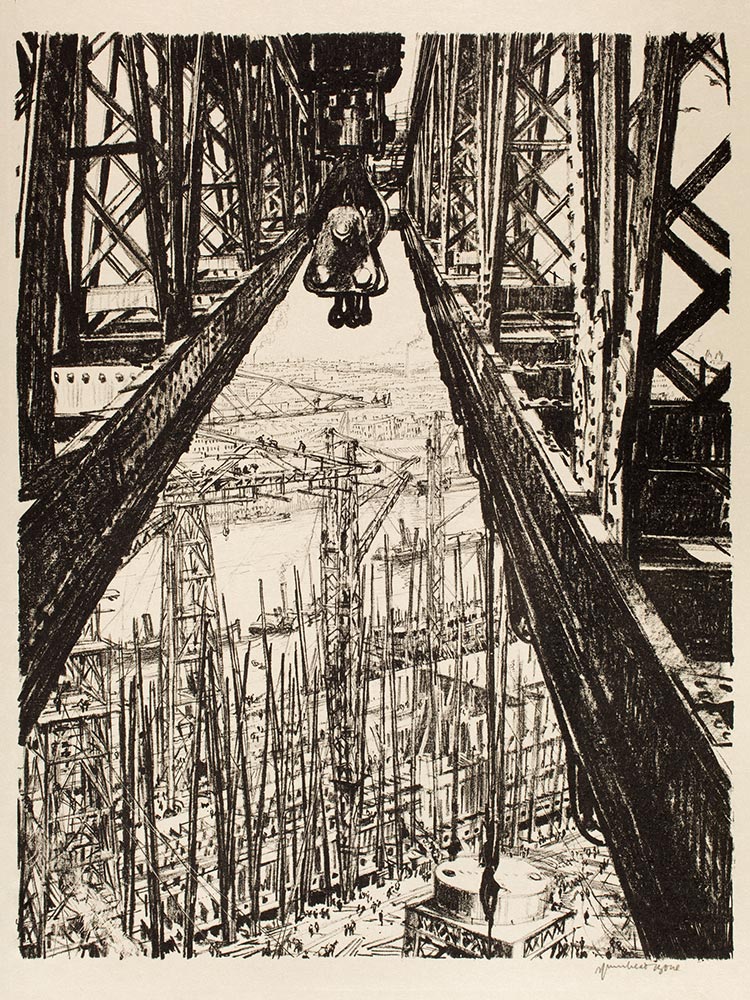

Muirhead Bone: Building Ships: A Shipyard Seen from a Big Crane (from THE GREAT WAR: Britain’s Efforts and Ideals), ca. 1917. Lithograph, promised gift of Frank Raysor. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

This Bone lithograph depicts a naval shipyard from atop a large crane. Bone, who served two tours of duty on the Somme, was known for his architectural drawings before the war. During the war, he often drew construction sites, demonstrating the vast behind-the-scenes network of machinery and people needed to fuel the war.

“His work demonstrated to those unfamiliar with the war effort the intensity and the grand scale required,” said Kristie Couser, who co-curated the print collection with Mitchell Merling during an earlier exhibition at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

As an artist, Bone was often compared with 18th-century Italian artist Giovanni Piranesi, known for sketching the ruins of the Roman Empire. Margulies also detects hints of cubism and other modern art techniques in Bone’s work.

“The love of the machine, the energy of the machine shown in pictures like this, all of that energy seems to lead to more abstract expressionism, like cubism,” Margulies said.

James McBey: The Sussex, 1916. Etching, promised gift of Frank Raysor. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Scotsman James McBey was on the shore in France on March 24, 1916, when a German U-Boat torpedoed the Sussex, a French passenger ferry. The above etching – which began as a drawing while McBey watched Allied soldiers rescue survivors and pull bodies from the wreckage – gave the shocked world a glimpse of the horror, which U.S. President Woodrow Wilson condemned as a human rights violation.

Despite the horror of his subject, Margulies said that McBey was among the more romantic of the war artists, creating poetic, ethereal scenes that resemble landscapes created by prominent English Romanticist J.M.W. Turner.

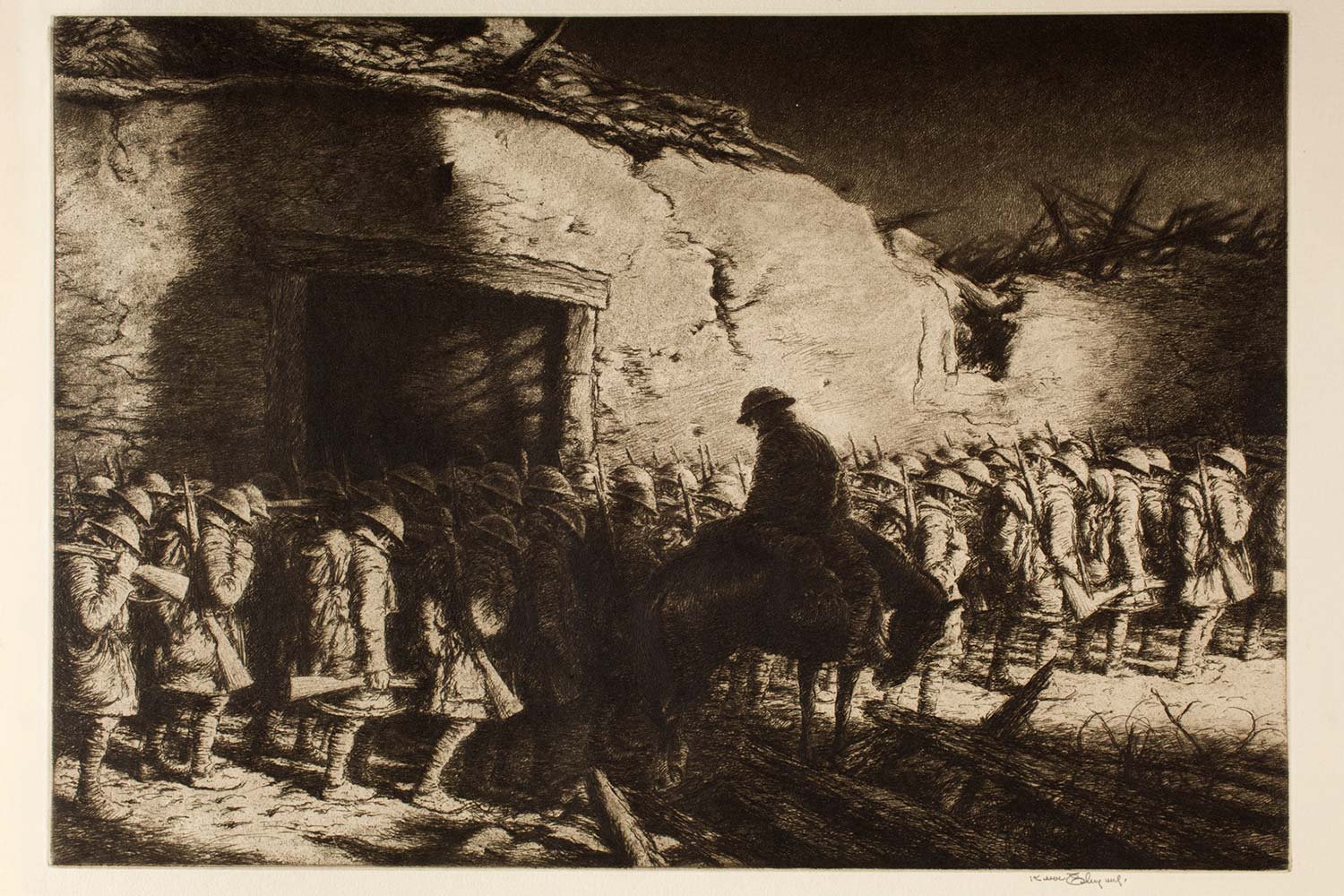

Kerr Eby: Shadows, 1936. Etching and sandpaper ground, promised gift of Frank Raysor. © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Eby was among the first American war artists. The above etching, which he drew from memory, shows American doughboys wearing their distinctive circular steel helmets, marching through ruins under the cover of darkness.

Unlike McBey, Eby quickly lost any romantic visions of war. He served another tour of duty in World War II and was so disturbed by what he had seen that he became a committed pacifist. In a book showcasing his work, which he dedicated to the soldiers who lost their lives, he wrote, “… of late years I have had a growing feeling that we who know something of what war means should get up on our hind legs and do or say what we can.”

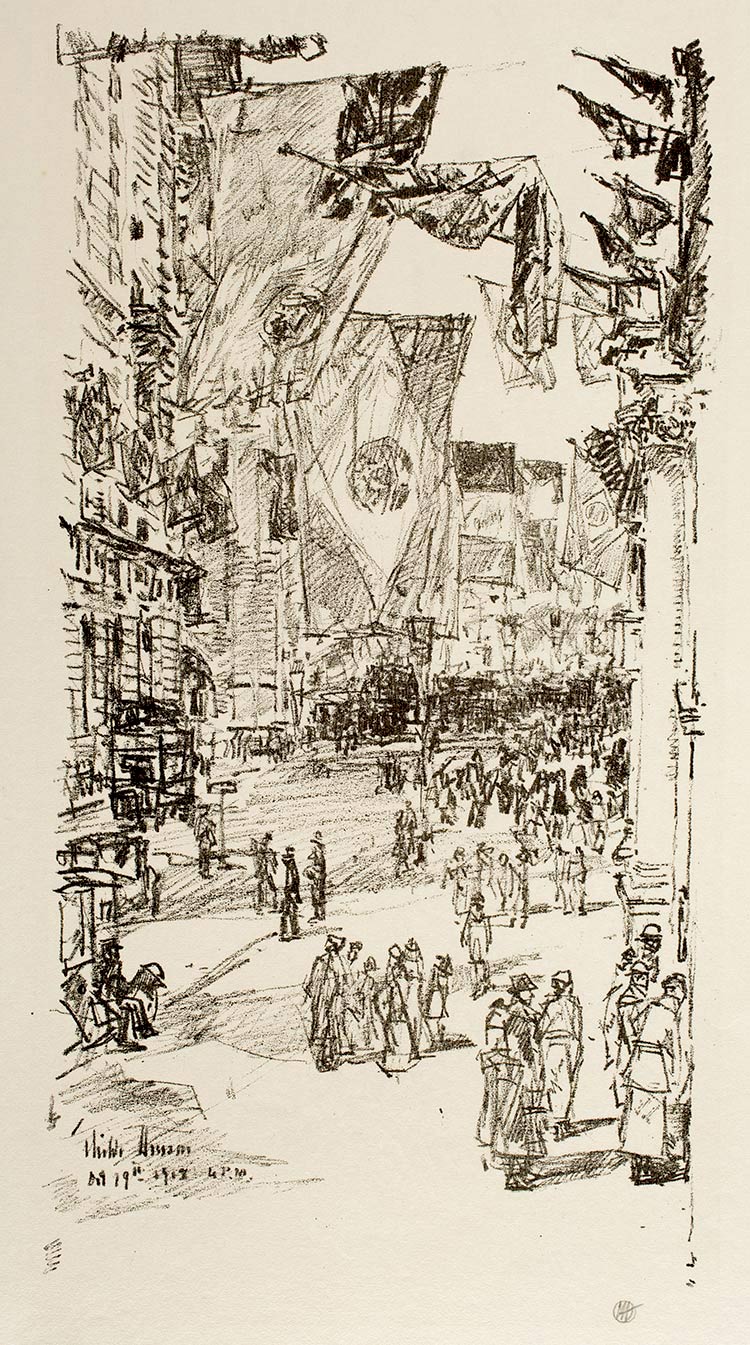

Childe Hassam: Avenue of the Allies, 1918. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. Lithograph, promised gift of Frank Raysor. Photo: David Stover © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

In the above lithograph, Childe Hassam, an American impressionist painter, depicted crowds thronging New York City’s Fifth Avenue to view window displays and flags promoting the sale of Liberty Loans. Each block was dedicated to one of the 22 allied nations fighting alongside the United States. Hassam’s drawing shows the Brazilian flag, representing the only independent South American country entering the war.

Hassam’s work is placed near the conclusion of the exhibition, offering a hopeful final note to an exhibition designed to emphasize the contradictions of war.

“World War I brought so much destruction, but there was also tremendous creativity that came out of it,” Margulies said. “Many of the problems that were created by the war have still not been resolved, and in many ways I still believe that we are fighting parts of this war today.”

Kristie Couser from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts will lead a Saturday Special Tour of the exhibition at The Fralin on Saturday at 2 p.m.

In addition to “THE GREAT WAR” exhibition, The Fralin will feature exhibitions including “A Gift of Knowing: The Art of Dorothea Rockburne,” showcasing the Canadian artist’s work that is informed by mathematics and astronomy; "Ann Gale: Portraits", an exhibition of oil paintings and sketches; and “New Acquisitions: Photography” showcasing The Fralin’s expanding photography collection. Dorothea Rockburne will visit the museum to give a talk, on Oct. 6. More information about each exhibition is available here.

The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia’s programming is supported by The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation.

Media Contact

Article Information

September 15, 2016

/content/art-trenches-drawings-world-war-soldier-artists