“Through the International Occultation Timing Organization, we share our findings with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and they update their public Horizons database of asteroid orbits with the data we collect,” said Teddy Oakey, fourth-year astronomy and physics major in the College of Arts & Sciences, as well as the group’s president.

The Occultation Group formed several years ago for occasional asteroid observations. Recently, it got a bit more organized.

In spring of 2024, the Occultation Group registered as a contracted independent organization and took its operations to the next level. By that fall, the group was observing multiple occultations a week and then several occultations every single night, Oakey said.

Mapping these celestial paths takes members across the country and around the globe. They’ve visited nearly two dozen states along with Australia, Mexico and South Africa. The group has a trip planned to United Arab Emirates, to track an asteroid which is a subject of a fly-by by the UAE spacecraft MBR Explorer, set to launch in 2028.

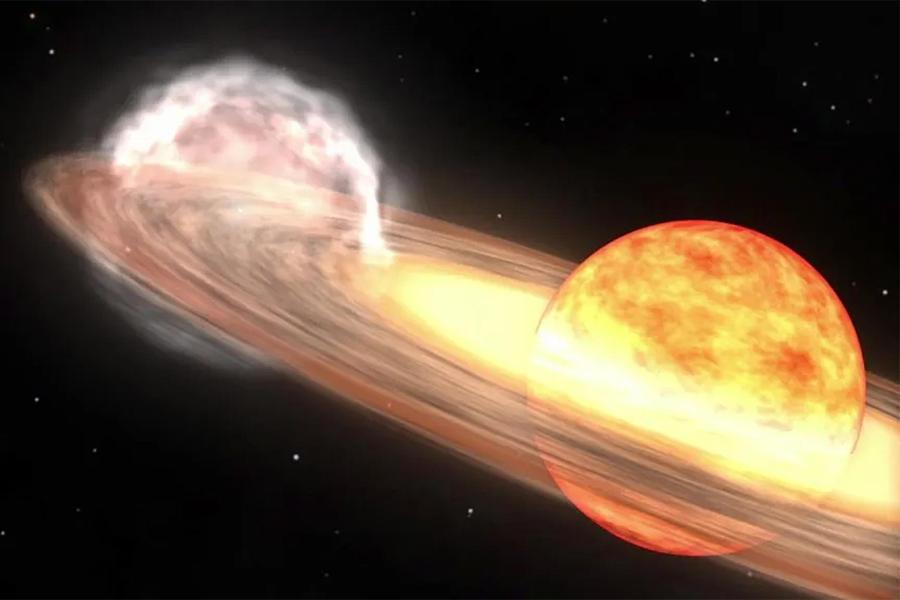

“Stellar occultation measurements are the most valuable tools to learn about asteroids before spacecraft fly-bys,” Oakey said. “MBR Explorer is set to visit seven main-belt asteroids, many of which have no prior characterization. Our team led three expeditions to observe one such uncharacterized asteroid, creatively called (59980) 1999 SG6, from this sample.”

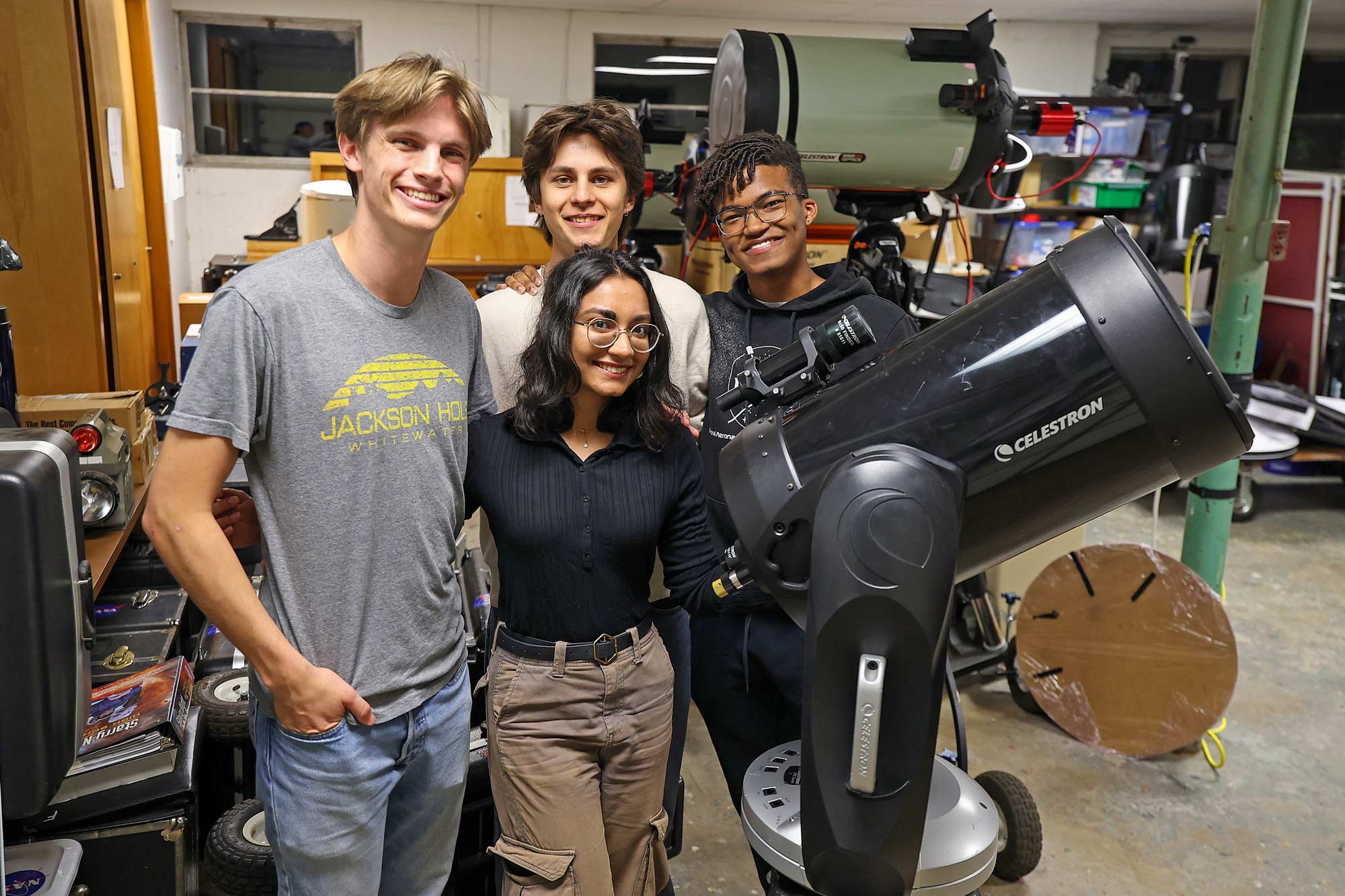

Not all observation points are exotic. Recently, four students set up two telescopes at the Astronomy Building as the sunlight faded. The telescopes were tethered to laptops on folding tables that recorded the asteroids’ paths. Four more undergraduates appeared out of the darkness, some of the group’s roughly 20 members, to assist monitoring asteroid sightings, some of which only last a second.

As darkness deepened, laptop screens illuminated anxious faces as observers checked whether their tracking was successful.

“We learned how to calculate when they’re going to happen,” Oakey said. “And so once we did that, we realized there’s actually several pretty solid chances to see these almost every night. So once we learned how to do it, it was just a matter of going outside and actually configuring a telescope. There are about 500,000 asteroids with orbits certain enough to generate predictions, and we observe about 40 on every clear night.”

Keya Garg, a third-year computer engineering major, flicked her fingers over the keyboard while Oakey secured the cable connection to the telescope, making sure the two machines talked to each other.

To Garg, raised in the United Arab Emirates, astronomy was a hobby, but her interest blossomed at UVA.

“I never thought I’d be out chasing asteroids in the middle of the night, but I love every second of it,” she said.

It is also important science, according to Oakey.

“We help to keep track of all of the asteroids in the solar system through our observations,” Oakey said. “This ‘keeping track’ is especially relevant when we study potentially hazardous asteroids, which have a non-negligible chance of impacting Earth within several hundred years. Our observations keep the orbits for these certain.”

Their research also helps in understanding asteroid composition.

“The profiling of an asteroid’s shape can tell us if we think it is a pile of rubble and boulders like the asteroid Bennu or a solid rock like Ida,” Oakey said. “The composition then informs us of the conditions that created the asteroid. By surveying the entire population of small bodies from Earth to Neptune and beyond, we begin to understand more clearly the conditions which birthed the solar system.”

Andrey Moore, a third-year astrophysics and computer science major, is the mechanic.

“I was elected as secretary, but effectively, I fix things,” Moore said. “As secretary, I keep the place organized, and I work on our spreadsheets and file system, but the thing that I really like doing is fixing things when they break.”

For Oakey, the experience has taught resilience.

“I have learned how to handle failure, because it can be really discouraging sometimes,” Oakey said. “We worked for six months for an occultation in South Africa, transporting all of our gear, all of our students, and we get there and it’s snowing on the night we needed to be clear.”