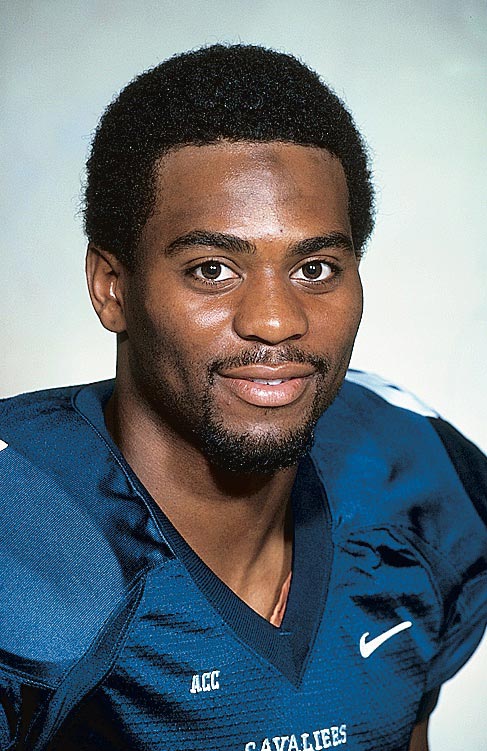

Who would have predicted, when Jay Dorsey was a University of Virginia undergraduate, that he would choose firefighting as a career?

Not Dorsey, who lettered twice at safety for UVA’s football team in the early 2000s.

“But after getting into this, I can’t see myself doing anything else,” Dorsey, 40, said recently at the McCue Center. “It fits my personality. It fits my makeup. It honestly just makes sense for me and who I am. When I tell [former teammates], they kind of shake their head, but a lot of them say, ‘We could see you doing that.’”

That’s the case with Marques Hagans, now the Cavaliers’ associate head coach. “It makes a lot of sense to me,” said Hagans, who played with Dorsey at UVA from 2001 to 2003.

“Dorsey was always different,” Hagans said. “Never afraid of anything. He was always a guy who kept everybody together. He just had that big brother-type spirit. So he’s always been like a protector, and never afraid of anything.

“Some people tackle, some people hit. He ran through you. He had no regards for slowing down. So he was just always different, and that’s the reason I say it doesn’t surprise me,” Hagans said.

Dorsey worked in Northern Virginia, Baltimore and then Philadelphia after graduating from the University in 2005. He didn’t know anyone in Philly when he arrived, and so his former UVA teammate, Jamaine Winborne, suggested that Dorsey contact Candyce Shelton.

Shelton, whom Winborne had met at UVA, from which she also graduated, was pursuing a master’s degree in nursing at the University of Pennsylvania. She’d already earned a nursing degree from Drexel University in Philadelphia.

“So I just made a phone call and said, ‘Hey, how you doing? What’s going on? I’m new to town,’” Dorsey recalled. “I was dating someone at the time. She was dating someone at the time. I think we went to the movies, went to a concert, and we’ve been together ever since.”

They married on 12/12/12. A few years later, they moved back to Charlottesville, Shelton’s hometown, where she’s a nurse practitioner at Pediatric Associates.

At the time, Dorsey had a job doing background checks for the federal government. He was intrigued, though, when Charlottesville firefighter Celia Thompson, who was married to the best friend of Dorsey’s father-in-law, mentioned one day that the city that was looking to hire more firefighters.

“So I just threw my name in the hat,” Dorsey said. “I went in cold, with no experience or anything.”

Dorsey says the same kinds of bonds he had with his teammates he now has with his firefighting colleagues. (Contributed photo)

Dorsey was accepted into the training program and he passed on his first attempt. He graduated from the fire department’s academy in March 2018. His current rank is firefighter/emergency medical technician/chauffeur, and he works out of the Ridge Street Station in downtown Charlottesville. (A chauffeur is a firefighter who’s qualified to drive the fire engine.)

“It’s a great profession,” said Dorsey, who’s the president of Local 2363 of the International Association for Fire Fighters. “I love it. I think in five years I may have had five days that I didn’t want to go to work. Maybe.”

His work reminds him of his days as a football player. “The camaraderie,” Dorsey said. “We train together. We sleep in the same house. We eat together. It’s so many correlations with a football team.”

Dorsey, who was born in Louisville, Kentucky, moved with his family to Jacksonville, Florida, when he was in elementary school His father served in the U.S. Navy and was stationed at Cecil Field. After graduating from the prestigious Bolles School in Jacksonville, Dorsey enrolled at UVA on a football scholarship in 2000.

He redshirted that season, the Wahoos’ last under head coach George Welsh. In 2001, Al Groh’s first year as Virginia’s head coach, Dorsey appeared in four games. He played in every game as a redshirt sophomore in 2002 and started five games in 2003.

Dorsey did not always take his studies seriously, however, and that sidelined him in 2004. He was placed on academic probation and had to leave school. He spent the year working as a bartender in Atlanta.

“I just didn’t apply myself,” Dorsey said of his academic issues.

Rachel Most, a dean in the College of Arts & Sciences, and Kathryn Jarvis, then the athletics department’s associate director of academic affairs, stayed in touch with Dorsey and encouraged him to complete his bachelor’s degree in anthropology. Spurred by their advocacy, he returned to Grounds and graduated in 2005.

“They were huge in me coming back,” Dorsey said.

His college football career may not have unfolded as he’d hoped, but Dorsey treasures his time at UVA. “The good memories I have are just with the guys that I met and continue to call my brothers, my friends,” said Dorsey, who remains close with Winborne, Ray Mann, Almondo Curry, Zac Yarbrough and Chris Canty, among other former players.

“I had a great time here,” Dorsey said. “My life wouldn’t be where it is if I didn’t go through what I did when I was at UVA.”

In Baltimore, Dorsey worked for the Miller Environmental Group, a hazardous response company. He helped clean up oil and chemical spills and regularly wore a hazmat suit and respirator. His six years with Miller, Dorsey said, helped prepare him for his current job.

“I never envisioned myself being a firefighter,” Dorsey said, “but when I worked for the hazardous response company, it was kind of the same. The only difference is that with the hazardous response company, I didn’t live at the house. But I was on call. Certain weeks you were on call, and you responded from home. So it would be more like a volunteer service for the fire department.”

Dorsey and his fellow Charlottesville firefighters typically work three 24-hour shifts every nine days. For example, he’ll work from 7 a.m. Monday to 7 a.m. Tuesday; from 7 a.m. Wednesday to 7 a.m. Thursday; and from 7 a.m. Friday to 7 a.m. Saturday, after which he’ll be off four days.

There’s no way of knowing how much sleep he’ll get on any given shift.

“It all depends,” Dorsey said. “We get medical calls, so chest pain or cardiac arrest or lift assist. Some people may fall, and they call us to help get them up and get them up. We also get called for motor vehicle accidents. And then obviously then we get called for fires.”

Firefighters spend a significant part of each shift honing their skills, Dorsey said. “I love the training, and we’re always doing something to better the community.”

Training can entail “going out in the rig and learning streets and driving the big engine is training for us, just getting familiar with the roads and just doing laps,” Dorsey said. “If a street is closed and we get a call, we might have to go this way instead of going that way.”

When crews are out on calls that don’t involve fire, Dorsey said, they often turn them into training exercises. “We say, ‘What would we do right now if this house right here were on fire?’ We pull lines, find out where the closest hydrant is, and we just kind of run through the motion of it being a fire. Our motto is: ‘We run a fire every day.’ Even though it’s not literally a fire. But putting lines on the ground, identifying the hydrants or where you would get your water supply from and different things like that keeps you sharp mentally, so that when it does happen it’s muscle memory.”

Dorsey and his wife have two children, sons Jay, 11, and Julian, 6, and they’re delighted to be raising them in Charlottesville.

“I love the area,” Dorsey said. “My wife is from here, and her parents are retired, so they help with our boys, our boys can see them.”

Hagans, whose sons Jackson and Christopher have played sports with Dorsey’s boys, is happy to see his friend back in town and thriving.

“I’m always praying for him,” Hagans said, “because I want him to be safe, but every time I see him in his uniform, he’s smiling. He’s happy. He takes a lot of pride in being a firefighter, and that’s really cool to see, because that’s basically a job of caring for people every day, rescuing and saving people every day. But that’s Dorsey.”

Media Contact

Article Information

October 15, 2025