June 25, 2008 — In the 1950s, the buildings designed by Chicago architect Louis Sullivan, known as the father of the modern steel skyscraper and one of America's most influential architects working predominately in the late 19th century, were falling out of favor and were being torn down.

Through the efforts of the late Crombie Taylor, a modern architect who pioneered the restoration of Sullivan's buildings with his reconstruction in the 1950s of the richly decorated interior spaces of the Auditorium Building located in Chicago; and Aaron Siskind, who directed an Institute of Design photographic investigation project of more than 60 Sullivan buildings, a unique, visual perspective of the architect's work has been preserved.

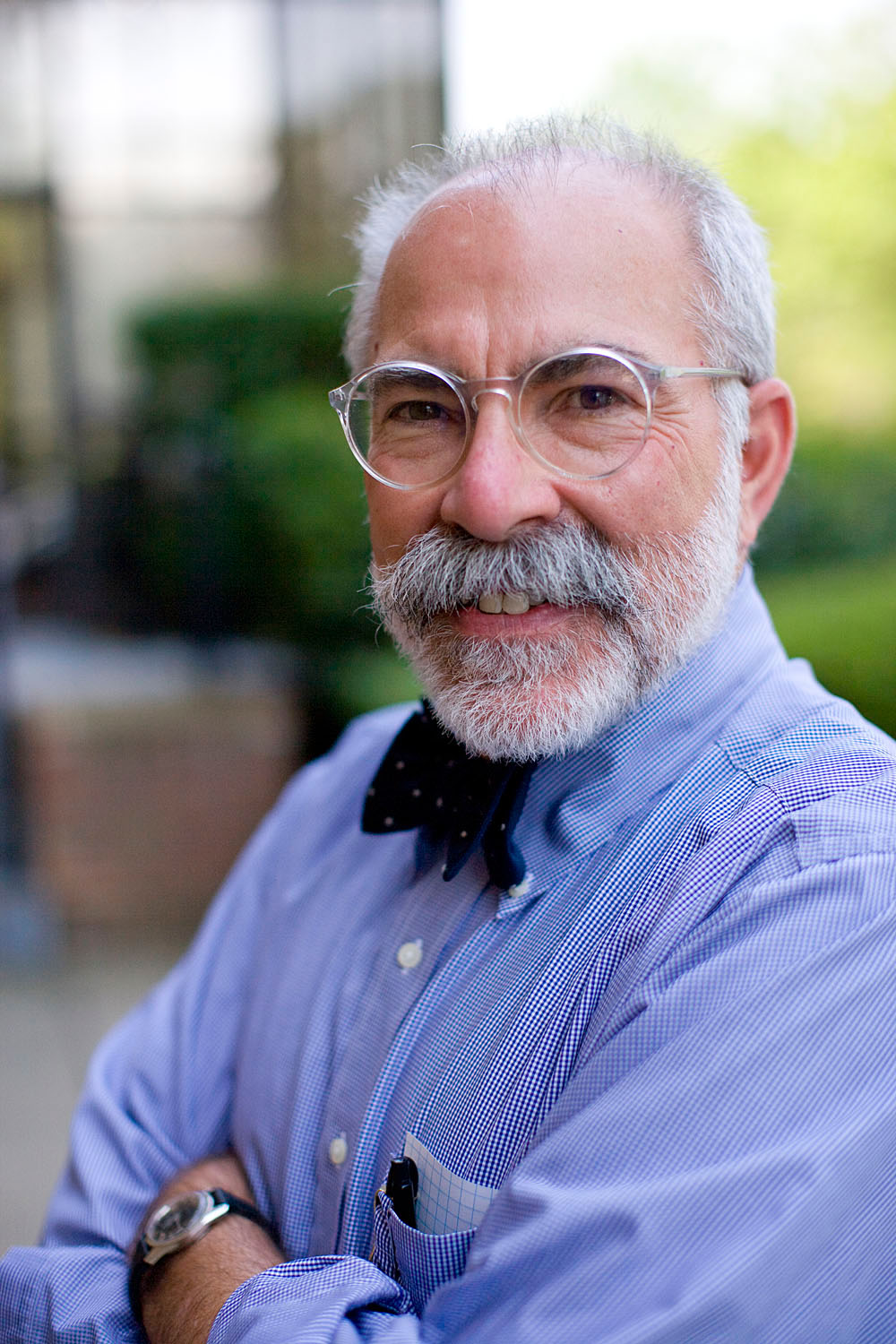

Jeffrey Plank, the University of Virginia's associate vice president for research and graduate studies, highlights the important contributions of these men in two new projects: a book, "Aaron Siskind and Louis Sullivan: The Institute of Design Photo Section Project," published this spring by William Stout Publishers; and a summer exhibition at the Illinois Institute of Technology, "Crombie Taylor, Aaron Siskind and the Adler and Sullivan Project," which Plank co-curated with John Vinci, an award-winning architect and an expert in historic building restoration.

"Aaron Siskind and Louis Sullivan: The Institute of Design Photo Section Project" publishes for the first time a 1954 exhibit of photos of Sullivan buildings taken by Siskind and students at the Illinois Institute of Technology's Institute of Design. Siskind led eight advanced photography students over a two-year period to bring the project to fruition. The exhibit, an unprecedented photographic documentary of Sullivan's architecture, included 130 photographs of 35 buildings. The students, working as a team with Siskind, produced 109 of the photographs. It was the largest exhibition of the work of Sullivan to date and never can be recreated because so many of Sullivan's buildings have been destroyed.

"The photographs of Siskind and his students mark a re-examination of Sullivan ornament — decorative elements that boasted cast metal and terra cotta tiles in interlacing organic and geometric patterns on building exteriors, and multi-colored stenciling used to create luminous, animated interiors — at a time when the unornamented International Style dominated architectural theory, if not architectural practice," Plank said. "And, as they capture Sullivan's buildings at the end of their lives, aged and worn, they also raise important questions about the fate of architectural landmarks. In Siskind's photographs the buildings achieve repose and dignity."

The images also brought attention to Sullivan's work and "set a new direction for the visual investigation of Sullivan's architecture," Plank said, adding that the exhibit "represented Sullivan as an artist and architect and invited close attention to elements of his buildings neglected by architectural historians."

In his installation design Siskind juxtaposed small building portraits and large ornament details to modulate the viewer's physical distance to the exhibit panels, bringing the viewer into an intimate relationship to some of the least studied parts of Sullivan's buildings. Other photographs of the backs of buildings or of buildings stripped of ornament provide a fresh perspective on building form and structure.

Sullivan's buildings, especially his interior spaces, provide early visual and physical examples of modern art concepts of space, color and movement, Plank said, and coincide with the teaching theories of Siskind and Taylor, who was the acting director of the Institute of Design in the early 1950s. In their role as teachers, they helped students explore firsthand the precepts of the Institute of Design curriculum that integrated art, science and technology in an atmosphere that fostered experimentation and problem-solving.

The 1954 exhibit was the largest photographic survey of Sullivan's work at that time. Siskind's plan to publish the photographs was never realized, and the images never were exhibited again — until this summer.

"Publication of these materials makes Sullivan a unique test case for further investigations about the relation of visual to textual information in architectural history," Plank said. "All of these Sullivan building photographs also make a case study in how perception of early modern buildings changes, from the very beginning to the very end of the modern period. Both of these issues — the importance of visual information and the changing perception of buildings — suggest new opportunities for architectural historians and historians of architectural photography."

Plank was familiar with the importance these Sullivan photographs played in Crombie Taylor's restoration work. In the 1990s, Plank joined Taylor in the rescue and restoration of Sullivan's Van Allen department store in Clinton, Iowa. Taylor had earlier used vintage photographs to restore Sullivan's Auditorium Building, the first restoration of a Sullivan building.

"To me, Taylor's use of those early photographs and his own need to understand and recreate every component of Sullivan's design as part of a restoration suggested that the use of visual evidence in architectural history needed further investigation," Plank said.

To that end, Plank began working on a trilogy of books. Plank published "The Early Louis Sullivan Building Photographs" in collaboration with Taylor in 2002. "Aaron Siskind and Louis Sullivan: The Institute of Design Photo Section Project" is the second book, and Plank plans an upcoming book devoted to Taylor and his pioneering contributions to restoration.

"If you want to understand how Sullivan's buildings work, you need visual evidence," Plank said.

This summer's exhibit, "Crombie Taylor, Aaron Siskind and the Adler and Sullivan Project," highlights that visual evidence. It includes photographs from the original exhibit, as well as Taylor's recreation of colorful original-scale stencils from the Auditorium Building and the demolished Garrick Theater in Chicago, which have not been exhibited since the early 1960s; vintage photographs of the Sullivan stencil recovery process; and more than 200 slides from a program featuring Sullivan-designed banks Taylor created in the early 1990s for educational use. It also includes examples of Taylor's modern architecture from the same period as the Sullivan photography project.

"Siskind's photographs and Taylor's restorations, recreations of polychromatic stencils and unsurpassed color slides were not noticed by architectural historians," Plank said. "Siskind and Taylor were not scholars, but they established an important body of evidence that could be reconstituted today."

The photographs and the exhibit are important because they have remained virtually unknown to historians studying Siskind.

"While Siskind's architectural photography was less well-known to his critics and biographers than his social documentary and abstract work, Siskind regarded it as the turning point in his career, a key to his turn from documentary to abstract photography," Plank said.

This is partly due to the fact that after the plans to publish the exhibit photographs were never realized, the negatives were turned over to Richard Nickel, one of the Institute of Design students who worked on the project, who went on to become a famous architectural photographer and preservation activist. Upon Nickel's death, they came into Vinci's possession.

"Vinci and I thought that publication of this Siskind exhibit would be an important contribution to Sullivan scholarship — and Siskind scholarship. It also should provoke some new interest in the Institute of Design at mid-century," Plank said.

The Chicago Tribune hailed the exhibit as "one of the finest of the year," and Plank moderated a photographers' roundtable shortly after the exhibit opening events to record the recollections of the former students who participated in the project. Mounted in Mies van der Rohe's recently restored Crown Hall the exhibit runs through Aug. 3

Through the efforts of the late Crombie Taylor, a modern architect who pioneered the restoration of Sullivan's buildings with his reconstruction in the 1950s of the richly decorated interior spaces of the Auditorium Building located in Chicago; and Aaron Siskind, who directed an Institute of Design photographic investigation project of more than 60 Sullivan buildings, a unique, visual perspective of the architect's work has been preserved.

Jeffrey Plank, the University of Virginia's associate vice president for research and graduate studies, highlights the important contributions of these men in two new projects: a book, "Aaron Siskind and Louis Sullivan: The Institute of Design Photo Section Project," published this spring by William Stout Publishers; and a summer exhibition at the Illinois Institute of Technology, "Crombie Taylor, Aaron Siskind and the Adler and Sullivan Project," which Plank co-curated with John Vinci, an award-winning architect and an expert in historic building restoration.

"Aaron Siskind and Louis Sullivan: The Institute of Design Photo Section Project" publishes for the first time a 1954 exhibit of photos of Sullivan buildings taken by Siskind and students at the Illinois Institute of Technology's Institute of Design. Siskind led eight advanced photography students over a two-year period to bring the project to fruition. The exhibit, an unprecedented photographic documentary of Sullivan's architecture, included 130 photographs of 35 buildings. The students, working as a team with Siskind, produced 109 of the photographs. It was the largest exhibition of the work of Sullivan to date and never can be recreated because so many of Sullivan's buildings have been destroyed.

"The photographs of Siskind and his students mark a re-examination of Sullivan ornament — decorative elements that boasted cast metal and terra cotta tiles in interlacing organic and geometric patterns on building exteriors, and multi-colored stenciling used to create luminous, animated interiors — at a time when the unornamented International Style dominated architectural theory, if not architectural practice," Plank said. "And, as they capture Sullivan's buildings at the end of their lives, aged and worn, they also raise important questions about the fate of architectural landmarks. In Siskind's photographs the buildings achieve repose and dignity."

The images also brought attention to Sullivan's work and "set a new direction for the visual investigation of Sullivan's architecture," Plank said, adding that the exhibit "represented Sullivan as an artist and architect and invited close attention to elements of his buildings neglected by architectural historians."

In his installation design Siskind juxtaposed small building portraits and large ornament details to modulate the viewer's physical distance to the exhibit panels, bringing the viewer into an intimate relationship to some of the least studied parts of Sullivan's buildings. Other photographs of the backs of buildings or of buildings stripped of ornament provide a fresh perspective on building form and structure.

Sullivan's buildings, especially his interior spaces, provide early visual and physical examples of modern art concepts of space, color and movement, Plank said, and coincide with the teaching theories of Siskind and Taylor, who was the acting director of the Institute of Design in the early 1950s. In their role as teachers, they helped students explore firsthand the precepts of the Institute of Design curriculum that integrated art, science and technology in an atmosphere that fostered experimentation and problem-solving.

The 1954 exhibit was the largest photographic survey of Sullivan's work at that time. Siskind's plan to publish the photographs was never realized, and the images never were exhibited again — until this summer.

"Publication of these materials makes Sullivan a unique test case for further investigations about the relation of visual to textual information in architectural history," Plank said. "All of these Sullivan building photographs also make a case study in how perception of early modern buildings changes, from the very beginning to the very end of the modern period. Both of these issues — the importance of visual information and the changing perception of buildings — suggest new opportunities for architectural historians and historians of architectural photography."

Plank was familiar with the importance these Sullivan photographs played in Crombie Taylor's restoration work. In the 1990s, Plank joined Taylor in the rescue and restoration of Sullivan's Van Allen department store in Clinton, Iowa. Taylor had earlier used vintage photographs to restore Sullivan's Auditorium Building, the first restoration of a Sullivan building.

"To me, Taylor's use of those early photographs and his own need to understand and recreate every component of Sullivan's design as part of a restoration suggested that the use of visual evidence in architectural history needed further investigation," Plank said.

To that end, Plank began working on a trilogy of books. Plank published "The Early Louis Sullivan Building Photographs" in collaboration with Taylor in 2002. "Aaron Siskind and Louis Sullivan: The Institute of Design Photo Section Project" is the second book, and Plank plans an upcoming book devoted to Taylor and his pioneering contributions to restoration.

"If you want to understand how Sullivan's buildings work, you need visual evidence," Plank said.

This summer's exhibit, "Crombie Taylor, Aaron Siskind and the Adler and Sullivan Project," highlights that visual evidence. It includes photographs from the original exhibit, as well as Taylor's recreation of colorful original-scale stencils from the Auditorium Building and the demolished Garrick Theater in Chicago, which have not been exhibited since the early 1960s; vintage photographs of the Sullivan stencil recovery process; and more than 200 slides from a program featuring Sullivan-designed banks Taylor created in the early 1990s for educational use. It also includes examples of Taylor's modern architecture from the same period as the Sullivan photography project.

"Siskind's photographs and Taylor's restorations, recreations of polychromatic stencils and unsurpassed color slides were not noticed by architectural historians," Plank said. "Siskind and Taylor were not scholars, but they established an important body of evidence that could be reconstituted today."

The photographs and the exhibit are important because they have remained virtually unknown to historians studying Siskind.

"While Siskind's architectural photography was less well-known to his critics and biographers than his social documentary and abstract work, Siskind regarded it as the turning point in his career, a key to his turn from documentary to abstract photography," Plank said.

This is partly due to the fact that after the plans to publish the exhibit photographs were never realized, the negatives were turned over to Richard Nickel, one of the Institute of Design students who worked on the project, who went on to become a famous architectural photographer and preservation activist. Upon Nickel's death, they came into Vinci's possession.

"Vinci and I thought that publication of this Siskind exhibit would be an important contribution to Sullivan scholarship — and Siskind scholarship. It also should provoke some new interest in the Institute of Design at mid-century," Plank said.

The Chicago Tribune hailed the exhibit as "one of the finest of the year," and Plank moderated a photographers' roundtable shortly after the exhibit opening events to record the recollections of the former students who participated in the project. Mounted in Mies van der Rohe's recently restored Crown Hall the exhibit runs through Aug. 3

— By Jane Ford

Media Contact

Article Information

June 25, 2008

/content/book-and-exhibit-jeffrey-plank-shed-light-architect-louis-sullivan-and-architectural