As the U.S. Supreme Court was deliberating the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954, John F. Merchant, a senior at Virginia Union University, was applying to the University of Virginia School of Law, knowing that being African-American would likely weigh against his admission. However, he was accepted.

Unlike most high-schoolers, he did not want to come here. Raised in Connecticut and only familiar with the historically black college he attended in Richmond, he was afraid of what it would be like at the all-white, all-male Southern university.

Nevertheless, administrators at Virginia Union University and his parents convinced Merchant to enroll, and he became the first black graduate of the Law School.

He tells the story of his struggles and successes in the book, “The Key to the Door: Experiences of Early African American Students at the University of Virginia,” published by UVA Press this spring.

Dr. Maurice Apprey, dean of UVA’s Office of African-American Affairs since 2006, procured a grant from the Jefferson Trust and worked with alumna Shelli M. Poe, now an assistant professor of religious studies at Millsaps College, to edit the volume as part of a larger project on the achievements of black students at UVA.

The book’s core includes first-person narratives from seven graduates who attended the schools of Law, Medicine, Engineering and Education, plus an interview with two local black women whose families provided a home away from home for many of these early students. Framing the personal stories are a preface by Apprey; a foreword from UVA President Teresa A. Sullivan; an introduction by English professor Deborah McDowell, who directs the Carter G. Woodson Institute of African-American and African Studies; and a historical overview of African-Americans at the University since its founding by library research archivist Ervin L. Jordan Jr.

The earliest black students who pushed open the door to the University came for a variety of reasons. Some individuals wanted to be trailblazers. Some, like Merchant, were reluctant. All sought a good education that would prepare them for a life, in most cases, better than their parents’. In the 1950s and ’60s, they were not exactly welcomed on Grounds, to put it mildly, but faced isolation, intimidation and mistrust. Nevertheless, they endured, secured their degrees and for many years, did not look back.

In recent decades, the University has invited them to return, to acknowledge their experiences, recognize their successes and welcome them as part of the UVA community – a more diverse, inclusive community compared to its past.

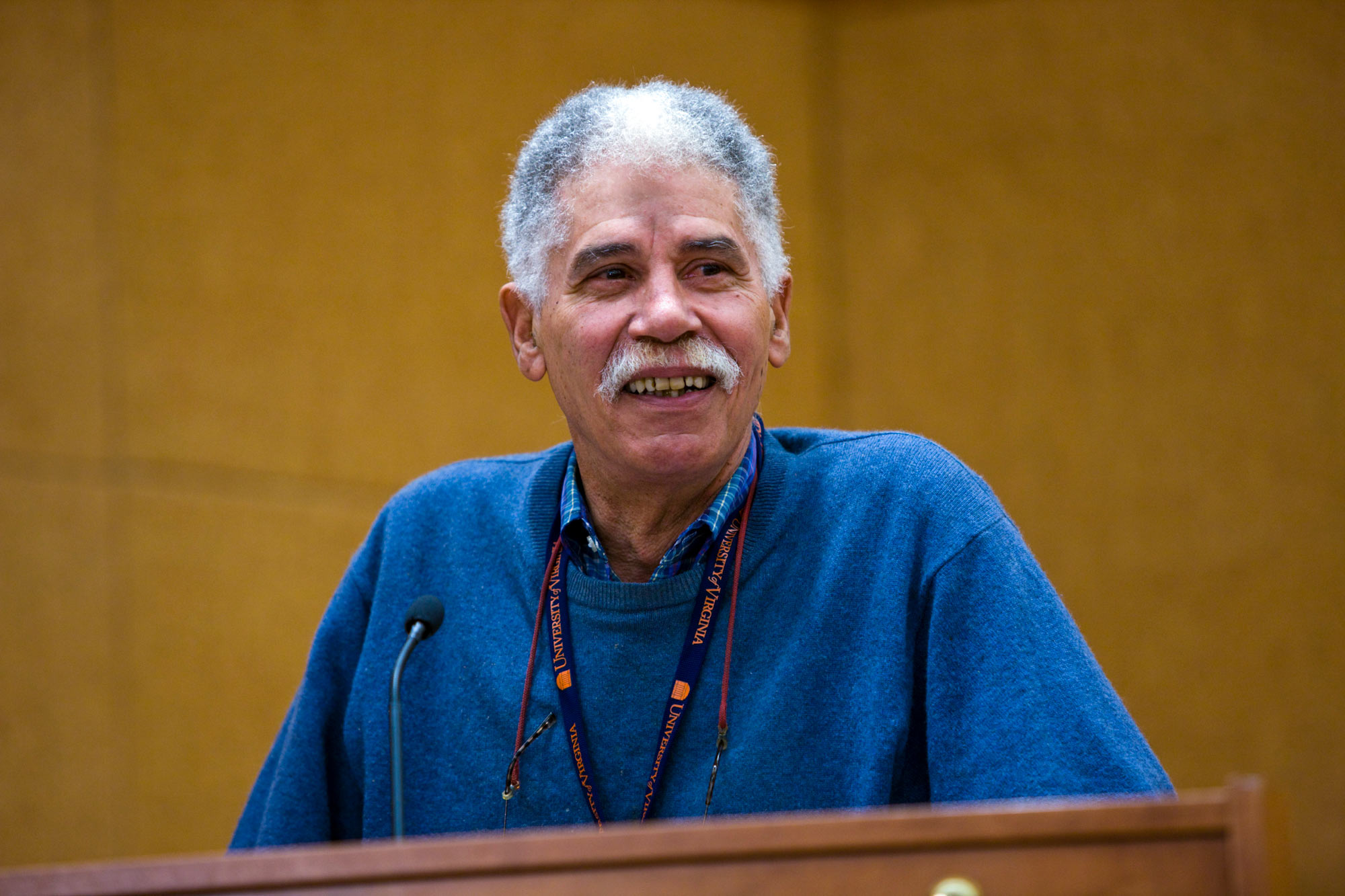

Maurice Apprey, who edited the book, says its title is “an apt metaphor for the courage of all the early graduates” and those who supported them. (Photo by Sanjay Suchak, University Communications)

“I decided to pay homage to this early group of black alumni … to recognize their contributions,” Apprey said. “For today’s students, it will give them a longer perspective.”

The personal accounts will give readers an opportunity to understand what it was like for these first black students, he said.

Although these alumni express a reluctance to dwell on the negative experiences, those incidents are hard to forget, they say, even as they describe how small gestures and certain people helped make the time bearable. They reflect on how their feelings have changed over time, especially as they have seen how much the University has improved.

“Fear is a strange thing,” Merchant begins his essay. From 1955 to 1958, he was the only black student in the Law School. (Gregory Swanson had sued for admission to the Law School, but left after one year, 1950-51, “following death threats and racial shunning,” Jordan writes.) Merchant was not allowed to attend social events because the venues barred African-Americans. By his third year, some concerned students offered to find a more welcoming place. Near the end of his first year, Merchant came down with mononucleosis and spent a few weeks in the segregated ward of the University Hospital. He was released in time to take all but one of his finals, and passed.

One thing that forever changed Merchant’s UVA experience came much later, when his daughter decided to go to the Law School, becoming the first black legacy student in the school. Without her knowing, he was invited to give the school’s graduation speech in 1994.

“It validated my three years there, erased many negatives from my mind, and set a stage for more to come regarding diversity at UVA,” he writes.

John F. Merchant, who became the School of Law’s first black student to graduate in 1958, returned to a special alumni reunion for pioneering African-American students in 2009. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Several other alumni had experiences that brought them full-circle back to a different UVA.

Dr. Vivian Pinn, a 1967 alumna and the second African-American woman to go through the School of Medicine, recounts several positive and negative incidents: a pair of white students who included her by asking her to be their anatomy lab partner; a landlord who had rented an apartment to her over the phone that she planned to share with the first black female medical student, Barbara Sparks (now Barbara Favazza), then said it wasn’t available after meeting them; and the dean who wouldn’t acknowledge or speak to her during her student years, but then wrote her a handwritten letter congratulating her when she was appointed the first full-time director of the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health in 1991. A year later, UVA’s Maxine Platzer Lynn Women’s Center gave her its Distinguished Alumna Award.

Pinn says she realized that if she wanted to see things change at UVA, it behooved her to get involved in supporting changes that were helping create a more diverse, inclusive environment on Grounds. She didn’t expect the changes to affect her so much. She became the first African-American woman asked to give the keynote speech at graduation, in 2005. Recently, the University decided to rename the School of Medicine’s main building in her honor.

Dr. Vivian Pinn, left, and Dr. Barbara Favazza, right, were the first black women to graduate from the Medical School. Alumna Susan “Syd” Dorsey, center, served on the Board of Visitors from 2003 to 2011. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

Willis B. McLeod, who proudly calls himself a trailblazer for his involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, said he never dreamed of attending UVA. His parents were sharecroppers and he was “literally born at the end of a cotton row” in North Carolina. An only child, he graduated in 1964 from Fayetteville State University in North Carolina and was working as a math teacher in Richmond when he was invited to a Curry School of Education leadership program alongside 14 black graduate students. He ended up earning his master’s degree from Curry in 1968 and Ed.D. in administration and supervision in 1977.

McLeod calls his UVA education “an essential experience,” saying it opened the door to a more successful professional life than he would’ve planned otherwise. Among other leadership roles, he served as chancellor of Fayetteville State from 1995 to 2003.

The book’s authors make a point of crediting the local African-American community with providing students like McLeod, Pinn and others a refuge from the prevailing hostile environment around them. Apprey interviewed Teresa Walker Price and Evelyn Yancey Jones, whose families opened their doors to feed the students and offer them stress-free break.

Aubrey Jones, who graduated from the School of Engineering and Applied Science in 1963, mentions that the engineering dean’s administrative assistant, Jean Holiday, was especially helpful to the few black students there at the time, as was an unnamed housekeeper who would encourage the small group and make sure they had an empty classroom for studying after hours.

The book’s final essay, “Opening the Door: Reflection and a Call to Action for an Inclusive Academic Community,” is partly devoted to the roles of African-American women who were not students, but influential as mothers and mother-figures, helpers or supporters of students. Authors Patrice Preston-Grimes, a Curry School professor and associate dean of African-American affairs; Dr. Marcus L. Martin, UVA vice president and chief officer for diversity and equity; Meghan S. Faulkner, an assistant in the Office for Diversity and Equity; and Poe also refer to Jordan’s historical essay and examples of those who took care of white male students’ and faculty families’ needs in earlier times, enslaved and free, as cooks, laundresses and seamstresses.

In reviewing the book, alumna Barbara D. Savage, who graduated from the College of Arts & Sciences in its second year of full coeducation in 1974 and now chairs the Department of Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, said, “Rarely has an institutional history been so well complemented by such compelling personal narratives. The pursuit of education is an enduring theme in black history, and this book brings that struggle and its successes to life.”

Media Contact

Article Information

June 16, 2017

/content/book-documents-struggles-and-triumphs-uvas-pioneering-black-students