They gathered in a one-room schoolhouse in Berryville, Virginia – four women and one man, all African-American, coming from their nearby retirement home.

They were there to tell Barbara Perry and Alfred Reaves IV, researchers at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, about one of their neighbors, an African-American man who journeyed from Berryville to the highest reaches of President John F. Kennedy’s White House and yet still came home nearly every weekend to see his family, friends and neighbors.

His name was George Thomas, and he was President John F. Kennedy’s personal valet. He accompanied Kennedy as the young Democrat’s political star rose, traveled the world at the president’s side and, ultimately, prepared the president’s body for burial after Kennedy was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963 – 55 years ago this week.

Thomas with John F. Kennedy Jr. in the White House at a birthday party for the toddler and his sister Caroline. (Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston)

As of yet, Thomas (who died in 1980) has made few appearances in the historical record. However, Perry, the Gerald L. Baliles Professor and director of presidential studies at UVA’s Miller Center, and Reaves, the center’s faculty coordinator, hope to change that.

Their quest began with a phone call from across the Atlantic.

Award-winning British screenwriter and playwright Nick Drake is working on a play about Kennedy’s 1963 meeting with British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. Instead of focusing only on the president and the prime minister, Drake is seeking to explore the wider cast of characters surrounding the world leaders, including Thomas.

“As many people do, Nick reached out to the Miller Center as the primary center studying the presidency,” Perry said. “He asked if we could give him more information about George Thomas.”

Intrigued, Perry and Reaves began digging through all sorts of historical records to find traces of Thomas, who was a domestic servant for notorious segregationist and Virginia senator Harry F. Byrd and newspaper columnist Arthur Krock before starting work in 1947 with Kennedy, at the time a young, single Congressman. Thomas was with Kennedy nearly every day, helping the politician – who had a bad back and could not even bend over to put on his own shoes – dress in the morning and undress in the evening. He helped with Kennedy’s physical therapy and treatments, maintained his wardrobe and in general ensured that the president had what he needed for the day.

“I had read a bit about him, but he was largely treated as a footnote in history,” Perry said.

Barbara Perry, left, and Alfred Reaves IV traveled to Berryville to talk with residents who remembered George Thomas and his years in the White House. (Photos: Amber Reichert, Miller Center)

Reaves began making calls to Berryville, a small town in the Shenandoah Valley near the West Virginia border, and was directed to the Josephine School Community Museum, housed in a one-room schoolhouse built for African-American children during the Jim Crow era. Norma Johnson, the head of the museum, knew of six local residents who had known Thomas personally and would be willing to talk about him.

That is how Reaves and Perry found themselves in the schoolhouse, recorders in hand, talking for more than three hours with men and women who remembered Thomas from their own adolescence, had worked alongside him, visited with him when he came home and mourned him when he died at age 72.

Joan Payne spent her childhood on Bundy Street, neighbors with the Thomas family. Maurita Powell knew George Thomas through her uncle, one of Thomas’ good friends. Josephine Lockley was a cook in the same house where Thomas once worked as a server; the two often sat out on the porch and talked after their duties were done. Randolph “Teddy” Brooks, a 94-year-old World War II veteran, worked construction in the Washington, D.C. area and often drove Thomas back to Berryville on weekends if he had a few days off from his White House duties.

Together, they described a man who was kind, meticulous and discreet as he worked his way up from his first job, serving at Sen. Byrd’s cocktail parties, all the way to the White House – and who, once he was there, “kept the secrets of Camelot,” as Reaves put it, never commenting on Kennedy’s personal life or sharing his memories with the press or with publishers.

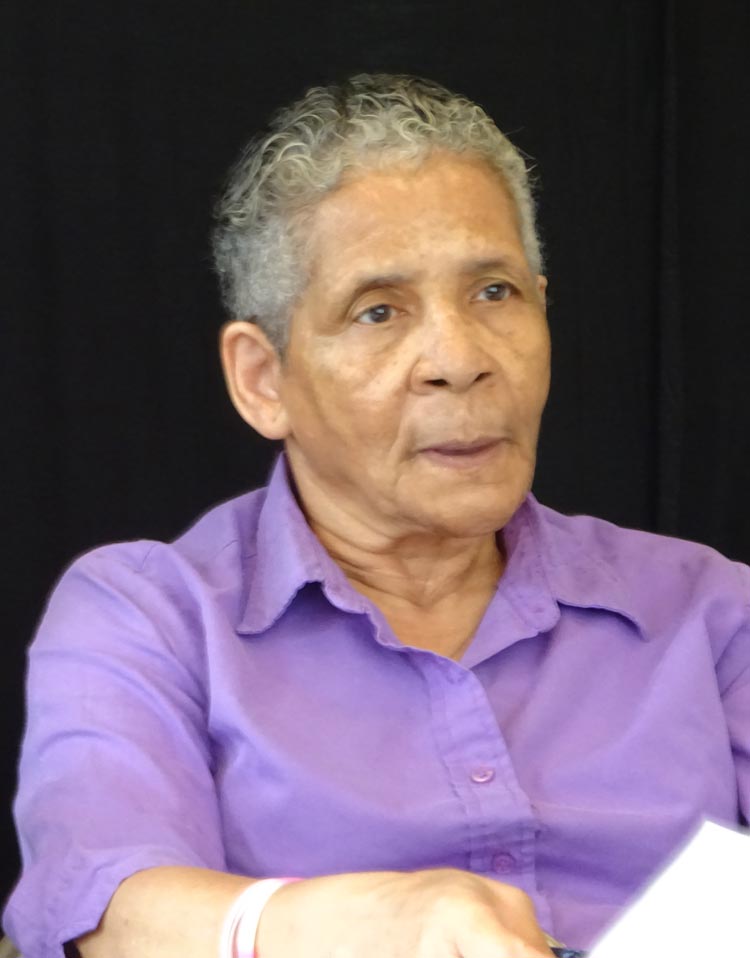

Joan Payne was one of five Berryville residents who gathered to talk about Thomas, her childhood neighbor. (Contributed photo)

“He worked for people at the highest levels of government, which says something about how good he was at his job,” Perry said. “And he was the soul of discretion.”

There are photos of him at the president’s last birthday party, playing with toddler John Jr., and later standing just a few feet behind Edward Kennedy at the president’s funeral, clearly grieving. He traveled around the world, from the famous 1961 summit in Vienna with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev to the Kennedy family compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, and finally to Dallas’s Love Field airport, where the valet accompanied the president’s body back to Washington and dressed him one final time, for his state funeral.

“In many ways, the Kennedys were George’s family, especially since he never married and had no children,” Perry said.

And yet, Thomas – whose grandparents were enslaved – clearly straddled two worlds, traveling back and forth between the wealthy, predominantly white world that the Kennedys inhabited and his hometown, a largely African-American community in the Jim Crow South.

Perry and Reaves believe Thomas’ experiences likely influenced Kennedy’s thinking on civil rights, which he began seriously considering near the end of his presidency. In a June 1963 address that laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the president lamented that “the grandsons of slaves are still not fully free.”

Could he have been referring to Thomas? Perry thinks so.

“We can’t make the leap yet that Kennedy got his ideas on civil rights directly from George, but it is certainly more than coincidental,” she said. “We are making the case that Thomas was the closest African-American to the president, and that he embodied the people and the struggles Kennedy talked about in that speech.”

Thomas, left, with President Kennedy and the first lady’s personal assistant, Providencia “Provi” Paredes, at a surprise birthday party for the president. (Robert Knudsen. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston)

Thomas’ story, the researchers said, is a prime example of the importance of studying not just the major players on the historical stage, but the many figures around them whose stories have been overlooked, silenced or otherwise gone untold, and people like the Berryville residents, who have their own stories and experiences to share of growing up during the Great Depression and living through World War II, the civil rights movement and other important moments.

“Even if there was not a lot written about George Thomas, he played an extremely important role in Kennedy’s life; it’s hard to imagine how the president would have gotten through the day without him,” Reaves said.

Perry agreed, comparing Thomas’ story with stories like “Hidden Figures,” the hit book and film about three African-American women who changed the course of the space race.

“This is why you do social history from the ground up,” Perry said. “There has been a shift in scholarship from ‘great man’ history – largely talking about powerful, white men like Kennedy – to more grassroots scholarship, including the people who worked behind the scenes and influenced these great figures.”

Perry and Reaves plan to continue researching Thomas and working with Drake as he writes his play. They are currently in search of Thomas’ grave, which they believe is near Berryville.

One day, they hope to have a historical marker placed at Thomas’ house in Berryville, noting his work with the president at a turning point in the country’s history.

Media Contact

Article Information

November 19, 2018

/content/british-playwright-trip-berryville-and-untold-story-jfks-valet