Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

For more than a century, historians have known that tens of thousands of black men fought for their freedom with the Union Army during the Civil War. Pieces of this history have been filled in over time: names and ranks, enlistment dates and locations, dates and place of death.

New research conducted at the University of Virginia’s John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History reveals a new layer of detail in the story of slaves fighting as liberators.

Using military and pension records and combining information in public databases, Nau Center researchers discovered that at least 240 black men born in Albemarle County fought with the Union Army. The men were former slaves and free blacks who served in the United States Colored Troops, a branch of the U.S. Army founded to recruit and oversee African-Americans in the Army.

“This is a very big deal,” said Elizabeth Varon, associate director of the Nau Center and Langbourne M. Williams Professor of American History. “These men were fighting because of their bonds to fellow soldiers. They had a keen commitment to the nation and they were fighting for their freedom. If the Union survives, they are part of a liberating army. They are entering the circle of liberators. If they win, they are free of the curse of slavery.”

If the Union survives, they are part of a liberating army. They are entering the circle of liberators. If they win, they are free of the curse of slavery.”

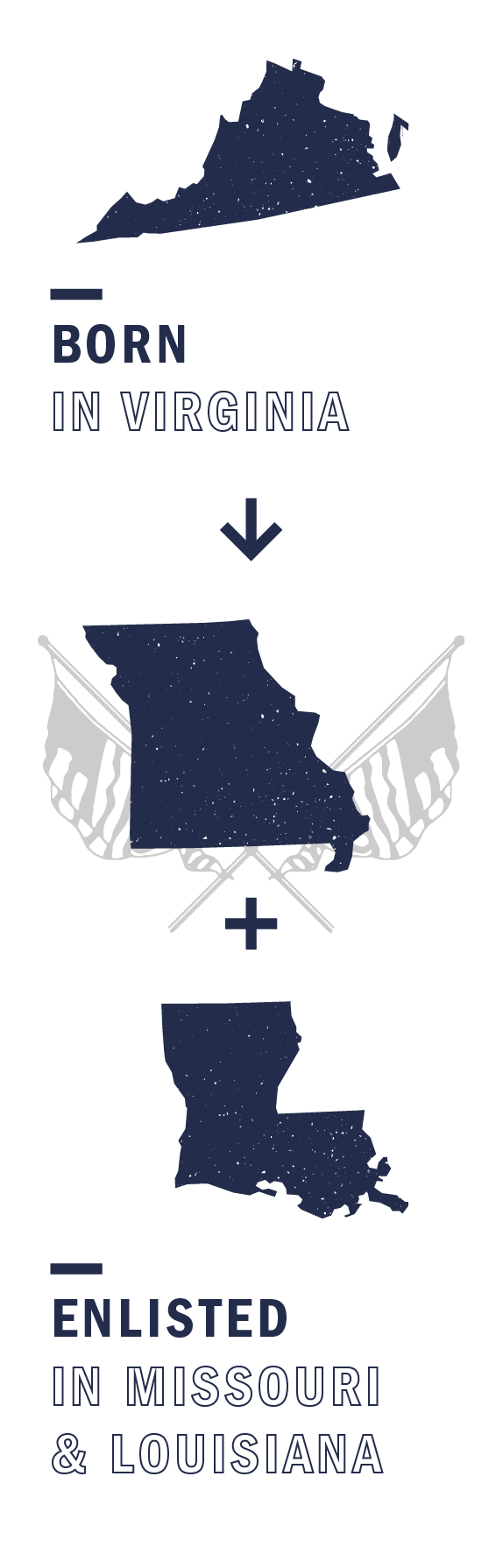

The former slaves were recruited by the Union Army in places such as Missouri and Louisiana, where they had been brought as slaves. But Army records noted their birthplaces, so with those records in hand, modern researchers were able to trace them back to Albemarle County.

It is the first time historians have quantified the number of African-Americans from Albemarle County who fought for the Union, and the research opens a new window on a part of Civil War history with relatively few details.

About 180,000 black troops enlisted in the Union Army, spread over about 160 regiments, and while historians have been aware of the contributions of the U.S. Colored Troops, the soldiers were usually tracked from where they were recruited, not where they were born.

“We had always looked at the USCT based on where most of the soldiers enlisted, such as Kentucky, Louisiana and Tennessee,” Varon said. “Factoring in where soldiers were born gives us a window on the diasporic nature of the slave trade and of slave flight.”

For example, 77 blacks from Albemarle County enlisted into Union forces in Missouri. Some traveled there with their masters, while others were sold to slaveholders in those areas. Slaves seeking to reach Union Army recruiting stations during the war had to weigh the risk of being captured by armed patrols of slave hunters; fugitive slaves who were tracked down by such patrols were whipped and returned to their masters, or shot in cold blood.

Varon was studying some Colored Troops enlistment records that the state of Missouri had posted online when she noticed several enlistees reported they had been born in Albemarle County. Inspired by this new insight, historians at the center pored through Union Army records, including enlistment and pension records, as well as genealogical databases, to determine from where the black soldiers came.

William Kurtz, managing director and digital historian at the Nau Center, further developed the project.

Albemarle County was considered to be exclusively Confederate territory. Before this, no one had a Union perspective on the area, And then we found all these men.”

U.S. Colored Troops regiments saw action in hundreds of engagements and dozens of major battles. Those units that did not see much combat nonetheless contributed to the war effort.

“USCT troops were at the Battle of the Crater, and the Siege of Petersburg and they were garrisoned at Vicksburg,” Varon said. “They also worked as engineers, carpenters and other trades the Army needed.”

“This is another window into Southern Unionism – the South against the South,” she said. “This was the South divided against itself.”

Kurtz was creative in searching for the databases, using several different spellings of Albemarle and Charlottesville to locate troopers from those locales and is collaborating with the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities at the University to create an internet accessible repository to hold and present the research results of the team to the public.

“The realization that 19th-century clerks often misspelled the county’s name proved useful as I continued to track down more men from Albemarle and its county seat, Charlottesville,” Kurtz said.

“Some of the Albemarle-born USCT soldiers moved away when they were quite young,” Varon said. “We are trying to find out as much as we can and we are reaching out to the genealogists and local historians. We are not the only group interested in the USCT entries and we are trying to connect with other groups.”

Of the 240 black soldiers from Albemarle County, very few, such as James T.S. Taylor and Nimrod Eaves, returned to Albemarle County after the war. After the demobilization of the Union Army, many former slaves settled in the North or returned to their families and communities in the post-emancipation South.

Kurtz said many of these men are remembered only because they did serve in the U.S. Colored Troops.

If they had not served, we would not have these records, and we would not know about their lives.”

So far, Kurtz has found no evidence that any of the men on the database worked at the University, but many were connected to Thomas Jefferson or Monticello.

“At least 18 men who went to Missouri and served together in the USCT were owned by Jefferson descendants,” Kurtz said. “John Coles Carter married Thomas Jefferson’s great granddaughter, Ellen Monroe Bankhead, and together they owned most of the slaves. A few also belonged to her brother, John Warner Bankhead, Jefferson’s great grandson.”

A freeman named George W. Lewis was a private in the 127th U.S. Colored Troops. He had belonged to Dr. Charles Everett, a Jefferson neighbor who had served as the personal physician to both Jefferson and James Monroe. Lewis was freed after Everett’s death in 1848 and moved to Pennsylvania before the war, living in a colony of freed blacks known as “Pandenarium.”

Kirt Von Daacke, an assistant dean in the College of Arts & Sciences who works with Varon on the President’s Commission on Slavery and the University, said the scholarship of the Nau Center is valuable for a variety of reasons.

Von Daacke said the Nau Center’s work supports the commission’s belief that the story of slavery at UVA is not contained within the University precinct.

“It is a story that, from the beginning in 1817, spills out toward Charlottesville, into Albemarle and several other counties – Fluvanna, Louisa, Orange, in particular, and even to at least as far away as Richmond, if not beyond,” Von Daacke said. “To understand the story of slavery at UVA is to understand the story of slavery in Albemarle, in Central Virginia, in Virginia, and even beyond.

“American slavery in the 19th century represented a deeply commodified system. Enslaved people were bought, sold and rented everywhere – the life stories of the USCT make this abundantly clear and they often enlisted at locations quite distant from Virginia.”

Gary W. Gallagher, director of the Nau Center, has been gratified by both the pace and the results of work on the black soldiers born in Albemarle County. “One of the center’s goals from the outset has been to pursue projects that yield benefits beyond the University and a strictly academic audience,” he said. “The USCT project has met that goal splendidly, illuminating local history and doing so in a way that other groups and institutions can emulate regarding black enlistees from other states.”

One of the center’s goals from the outset has been to pursue projects that yield benefits beyond the University and a strictly academic audience.”