Charlie Tyson is a fourth-year political and social thought and English major in the College of Arts & Sciences, who also writes for the Office of University Communications. He recently got a chance to visit the U.S. Supreme Court, and here shares his recollections.

February 22, 2014 marked eight years since Justice Clarence Thomas last asked a question during an oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court. Five days after this curious anniversary, I traveled to Washington, D.C., to visit Thomas with two fellow undergraduates and students from U.Va.’s School of Law. (More on how the opportunity came about later.)

As I sat in the Supreme Court building’s east conference room, waiting for Thomas to arrive, I wondered: what will a famously silent judge have to say? But before I would discover that, I learned about the history of the building itself.

A building of its own

For much of our country’s history, the U.S. Supreme Court had no building to call its own. When the federal government moved from Philadelphia to Washington in 1800, the Court tailed behind Congress hoping for a space to gather.

The court would become less timid – politically, at least – three years later, when Chief Justice John Marshall institutionalized the principle of judicial review in Marbury v. Madison. But the problem of place remained. The court lacked a home. For more than a century, Congress lent it various rooms in the Capitol Building.

In 1929, Chief Justice William Howard Taft grew sick of squatting. Taft, who had served as president before jumping to the judiciary, urged Congress to approve the construction of a separate building for the court. The building was completed in 1935. In a rare event for the government, the project came in under budget.

Back to present day

Last week I found myself standing in front of this building for the first time. The court’s building is new compared to the Capitol, old compared to much of Washington’s frantic urban development. The front side of its neoclassical façade bears a motto: “Equal Justice Under Law.”

The motto seems redundant. What sort of justice is applied unequally? Unequal justice is hardly justice at all. But as I gazed at the marble etching, I felt profoundly moved. And it was the inclusion of the word “equal,” redundant or no, that summoned my surge of emotion. A nation of equal citizens under the law: a startling and beautiful idea, even hundreds of years after the founding.

Arrival in Washington

The Court has always been my favorite branch of government. In theory, the legislature is our most democratic institution: it brings together a panoply of voices representing the nation’s diverse interests. In recent years, however, it’s been difficult to hold much affection for Congress.

The executive branch, more than any other arm of government, can craft a compelling vision for the country’s future. But the consolidation of executive power in an age of emergency powers and nuclear weaponry has left me uneasy.

Removed as it is from much of the politicking and strategic maneuvering that characterizes Washington, the Supreme Court seems, to me, the most pure faction of government. Justice is blind, but the justices seem clear-eyed – more so than the rest of the government, anyway. When I learned about the court as an adolescent, I recognized, with a stirring of awe, that the difficult work of interpretation was essential for the maintenance of society, and that thought and action were often one and the same.

I was in Washington by way of a happy accident. Over the summer, I had worked for U.Va. law professor A.E. Dick Howard, who teaches a seminar on the Supreme Court. A man of many connections, he had arranged for his class to visit the nation’s highest tribunal. He generously invited me and two other undergraduates to join, perhaps praying quietly that our wrinkled clothes and utter lack of legal knowledge (in comparison with our intelligent and preened Law School friends) would go unnoticed.

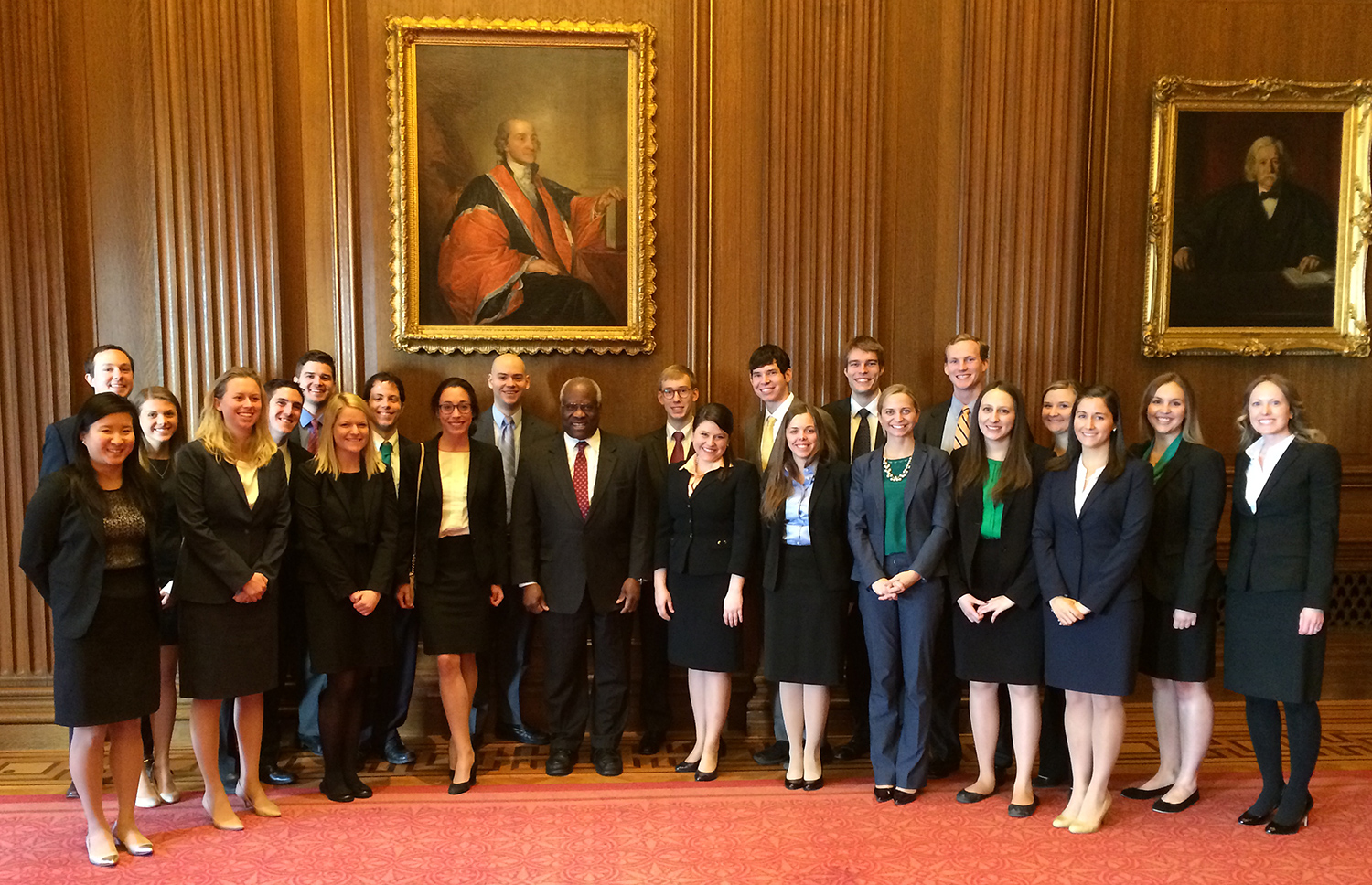

In typical undergraduate fashion, we didn’t leave for the 10 a.m. court visit until after 7 o’clock in the morning. To us, it felt like the middle of the night. (Our Law School colleagues had left Charlottesville at 5:30.) We raced to the Supreme Court building, sidled through the body scanners and tumbled into the east conference room, where Justice Clarence Thomas was scheduled to speak to us, at 10:10. Luckily, Thomas was late as well.

The silent judge speaks

Like many famous people, Clarence Thomas is shorter in person than you would expect. His height, however, wasn’t the only quality that made him approachable. Given Thomas’ somewhat stony public persona, I expected him to exhibit an element of reserve or defensiveness. I was wrong. Instead, I encountered a person of tremendous affability.

He walked in without fanfare. One moment we were all chattering among ourselves; the next we were standing up, as custom demands, and watching Thomas walk to the front of the room. Thomas broke the tension with a joke about Virginia sports and laughed loudly, setting us at ease. With a law student’s help, he gamely lifted a table that had been set at the front of the room and pushed it out of the way, leaving him more room to stand.

Thomas spoke for a few moments. Most of the session, however, was dedicated to questions.

The content of Thomas’ answers was not surprising. He affirmed his commitment to originalist constitutional interpretation, as well as his disdain for affirmative action. He told me he had little respect for the media, yet he acknowledged that cameras in the courtroom would probably be an inevitable development (currently the court allows audio recordings of arguments and decisions, but no video).

He was wonderfully open about life on the court. Speaking with him helped demystify the processes of argument and deliberation that make up much of the court’s work. He even explained where at the table each justice sits during meetings. He spoke highly of his colleagues. He repeatedly emphasized the importance of civility and politeness. To do his job well, he said, he had to treat his colleagues with respect and kindness.

I was fortunate enough to ask the last question of the morning. Moments before, a law student had asked him if he read much academic legal scholarship. He said no – but he read novels. I raised my hand. How had his exposure to literature, I asked, colored his legal thought and legal writing?

Thomas reminisced about majoring in English as an undergraduate at the College of the Holy Cross. For him, majoring in English was like majoring in a second language, he said. He had grown up in a community where people looked down on you for “speaking proper.” One thing literature had taught him was the value of clear communication. The court’s opinions should not be incomprehensible, Thomas said.

“What does your mother do?” he asked me. I told him. (She’s a public health survey researcher.)

“I want to write opinions so that your mother could read them,” he said. His point was that you shouldn’t need a law degree to understand the law of the land.

Time was up. As I walked out of the Supreme Court building, I looked again at the motto: “Equal Justice Under Law.” Thomas’ jurisprudence aside, two of his values that came through that morning – his dedication to civility and his commitment to clear writing – were, I thought, in accord with this governing principle. Part of justice is treating people equally. Civility enacts just relations in miniature, in an extralegal sphere. Codes of politeness at their worst can be constraining, or they can enforce social hierarchies. At their best, however, they help us acknowledge others as full persons, with needs, desires and values that may differ from our own.

And there is something democratic about clear writing, too – about trying to create opinions that all citizens can read and understand.

If I came away that morning with a richer understanding of law and justice, Thomas’ candor had something to do with it. His openness helped me understand him not as a stony, silent figure, but as a fellow person. He began to speak, and his humanity shone through.

After graduating from U.Va. in May, Charlie Tyson will attend Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar to pursue two master’s programs, one in Victorian literature and another in history of science, with a goal of being a writer and professor upon completing a Ph.D. in the U.S.

Media Contact

Article Information

March 11, 2014

/content/clarence-thomas-talks