Since the first COVID-19 case was discovered in the United States in January 2020, there have been 32.8 million positive cases and three periods of significant rate increase, or waves, as of May 11.

Three University of Virginia sociology students devoted their distinguished major theses to investigating several critical issues that have emerged from the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S. They had to address statistics and situations changing on a daily basis, not to mention being isolated and unable to work in-person on parts of their projects.

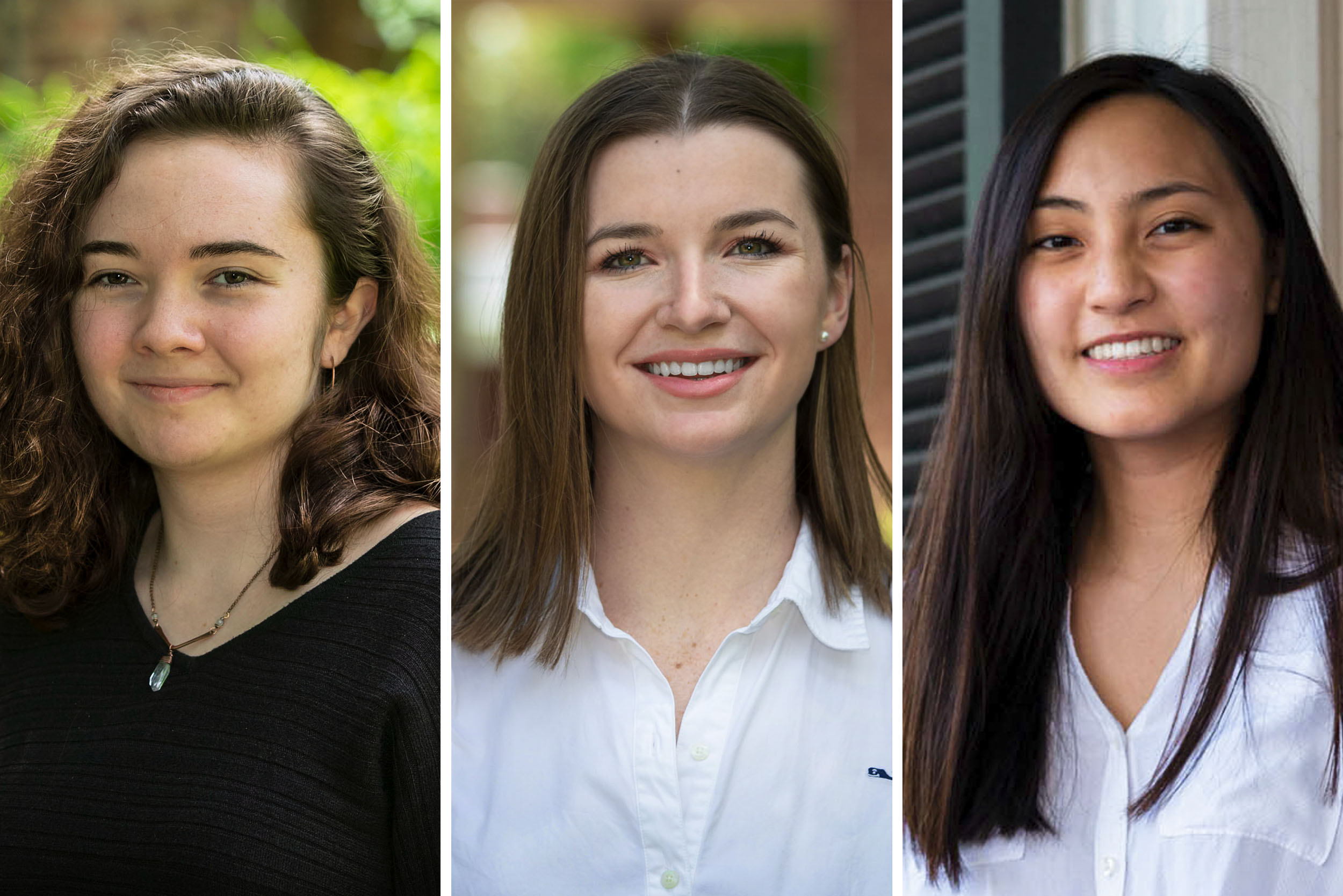

Madeleine Peterson, Rain Sabin and Christine Siu, who graduate May 22, succeeded in doing sophisticated analyses for projects concerning COVID-19, the social determinants of health and their impact on racial and ethnic groups.

“Each of their projects sheds new light on the well-known racial and ethnic differences in morbidity and mortality from this pandemic,” Tom Guterbock, director of undergraduate programs in sociology, said.

Natalie Aviles, an assistant professor of sociology who specializes in medical sociology, directly supervised Peterson’s and Siu’s theses and was the second reader on Sabin’s.