Tapping on the keys of an electric typewriter sounded familiar to some of the University of Virginia students – even though they had never used one before. They are, of course, most familiar with laptops and cell phones.

“It sounds like writing,” one student said.

Assistant Professor of English Patricia Sullivan has taught “Writing as/and Technology” for several years in different seminars for first-year students and advanced undergraduates, under various titles such as “From Bard to Blogger, and Back Again” and “Composing Digital Essays and Stories.”

Students learn about the history of writing and printing and work their way into 21st-century digitization, including multimedia, hyperlinks and voice dictation. They gain new appreciation for old methods and explore – even predict – where communication is headed in the digital age. They also examine their own perceptions of writing systems, such as the use of pen and paper versus various machines.

“Students don’t often think of writing as a technology,” said Assistant Professor of English Patricia Sullivan. She teaches students “tools, materials and systems – they all affect culture and cognition.” (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

“Writing, although invented thousands of years ago in human culture, seems natural, but it’s not,” Sullivan said. It’s not the same as the natural development of spoken language. Students often think of it as a record of speech, but it’s not really that, either, she said.

Through writing, humans have created and continue to produce records of civilization – important areas in knowledge, history, law, trade, art and science. Writing and reading encourage reflection, she said.

“Students don’t often think of writing as a technology. Tools, materials and systems – they all affect culture and cognition,” Sullivan said. “A lot of what we understand as knowledge has been recorded in writing.”

Students made their own ink and tried different kinds of nibs and goose quills in the Wilson Hall maker studio, as part of the “Writing as/and Technology” course. (Photo by Jason Bennett)

Sullivan is teaching two sections of the seminar to Echols Scholars this semester. The Echols Scholars program is an honors program in the College of Arts & Sciences for academically exceptional students who are exempt from curriculum requirements and can create their own interdisciplinary majors, among other benefits.

For the past three years, the Academic and Professional Writing Program has been offering first-year Echols Scholars an opportunity to take a writing course, even though they’re not required to, said Associate Professor of English James Seitz, who directs the program. “We’ve been filling six sections a year with students who choose to take writing, even though they don’t have to,” he said.

Emily Lin wanted to take Sullivan’s course “to explore how technology has impacted different forms of writing over the years, and perhaps how writing has impacted technology,” she said. “Advancements in technology have always been changing the way we live, work, play – and yes, even the way we write.”

Chirag Kulkarni said he’s “always been fascinated with technology and science, while at the same time passionate about writing. This course seemed like the ideal intersection of the two fields.”

Sullivan took students to the Wilson Hall maker studio for some hands-on experiences with early writing methods. She enlisted the help of specialist Jason Bennett of the Arts & Sciences Learning Design and Technology team, a group that collaborates with and aids faculty as they explore how to incorporate innovative pedagogies and instructional technologies into their courses.

Some students made clay tablets and tried writing on them with simple tools; others made their own ink and tried different kinds of nibs and goose quills. “We made a mess!” Sullivan said, adding that the students were surprised at the range of writing materials and systems, and how laborious the processes were.

When Special Collections curator Molly Schwartzburg showed students one of the first-known printings of the Declaration of Independence, many took out their phones to take photos of the historic document. (Photo by Patricia Sullivan)

The classes also visited the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, where curator Molly Schwartzburg showed them one of the first-known printings of the Declaration of Independence. Many in the group took out their phones to take photos of the historic document. Sharing photos on social media, they were enacting one of the latest means of communicating with today’s technology.

Schwartzburg also showed them a Greek fragment on ancient paper made from papyrus, an illuminated medieval manuscript and a page from a mid-15th-century Gutenberg Bible, the first book printed in Western Europe with moveable metal type.

The class also went to the Robertson Media Center’s Digital Media Lab in Clemons Library to try out dictation software and use a few recording experiments to compare how well the devices recorded speech. “It’s better than it used to be,” Sullivan said.

Opposition and concerns have often accompanied major shifts in communication methods at every turn: Plato, for example, worried that writing would ruin human abilities to remember and to carry on conversation, to pass down culture, stories and important subjects like history and philosophy through oral means. The printing press in the 15th century quickly and radically changed the way knowledge was shared. Writing and reading, separated from face-to-face communication, could be promiscuous and subversive.

Now, as humans spend so much time reading and writing online, researchers are studying the differences; so far, recent studies have found that note-taking by hand results in better understanding, and that when reading online content, users tend to skim or scan, and are more easily distracted.

To that point, Sullivan sometimes asks her students to print out assigned scholarly articles to better focus and take notes. And part of the class time is conducted as a workshop where students discuss and critique each other’s writing.

The course has a definite online component, however, using UVA’s Collab system, which enables students to hold interactive discussions and virtual meetings and to securely store and share their work. They also create and maintain shareable electronic writing portfolios, where they keep track of drafts, comments and revisions. Practicing and improving their writing, after all, is the main purpose of the course.

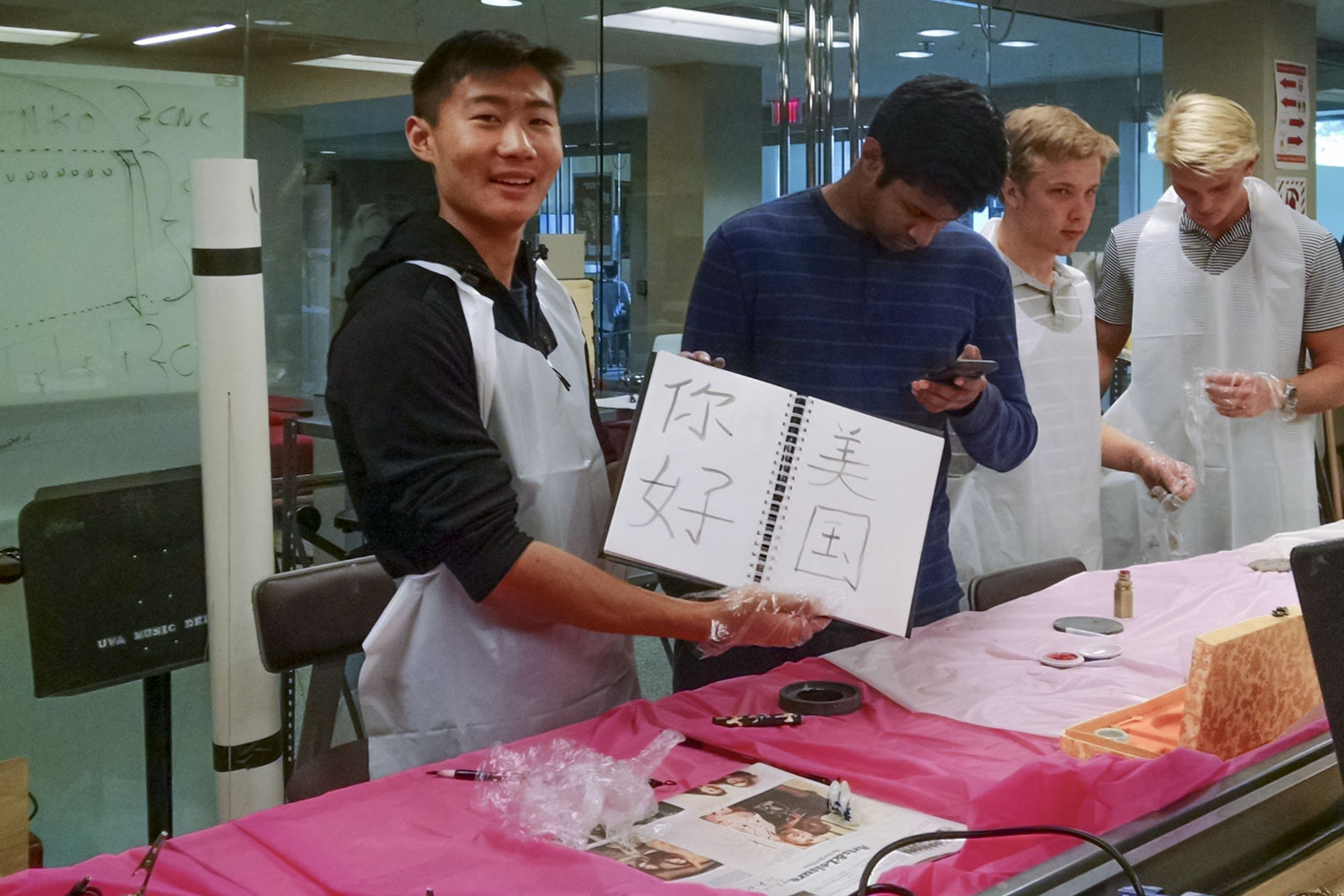

Richard Song demonstrates Chinese calligraphy, which he learned from his grandparents. (Photo by Patricia Sullivan)

“Writing is an important skill to have,” said another student, Richard Song. “Professor Sullivan has been helpful with revision and constantly improving.”

Interested in artificial intelligence, Song researched and wrote about robot journalism for one of his assignments. This kind of software – not really robots – uses algorithms to write articles that report on things like sporting events and weather forecasts using stock phrases. “The speed and objectivity of robots best suits them to create formulaic articles on topics such as sports, finance, and weather, while the creativity and insight of human journalists uniquely position them to produce in-depth analysis and investigative reporting,” Song writes.

Lin chose to write about expressive writing for her assignment. A technique used to treat depression, “expressive writing is like journaling, where you write about and reflect on your thoughts and experiences,” Lin said. “Typically, the technique works for clients with low or mild depression, but it may worsen the symptoms for clients suffering from more severe depression. My essay is about how expressive writing employs the cognitive (thinking, reasoning, rationalizing) areas of your mind to alter the emotional areas (affected by depression). This mechanism makes sense because a difference in how the client employs the cognitive area might explain the distinct results which different clients have after undergoing this type of writing therapy.”

For Lin, the experience of taking this course has changed her view of academic writing. “I had been used to dry, jargon-laden prose in academic writing, and I thought it might be the only way you can appropriately present complicated topics. However, I now realize that writing can be both academically complex and enjoyable to read, if the writer might take the time to write engaging prose,” she said.

Kulkarni, too, said he has “learned how to write academically in an exciting way. Usually, you either write with passion or you write scientifically. Professor Sullivan taught me how to do both simultaneously.”

This kind of enthusiasm about a writing course is music to Seitz’s ears.

“This is an example of extremely engaging pedagogy that is also helping students to see that writing technology isn’t something that arrived during the computer age, but that has always affected how we communicate,” he said. “Writing courses are so often portrayed as a requirement to be checked off and left behind, but this course offers a different model, one in which students register for a writing class because they’re eager to write and learn more about the history of writing.”

Media Contact

Article Information

November 17, 2017

/content/clay-tablets-computer-tablets-course-explores-writing-and-technology