During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union routinely spied on each other using high-altitude reconnaissance aircraft and space satellites.

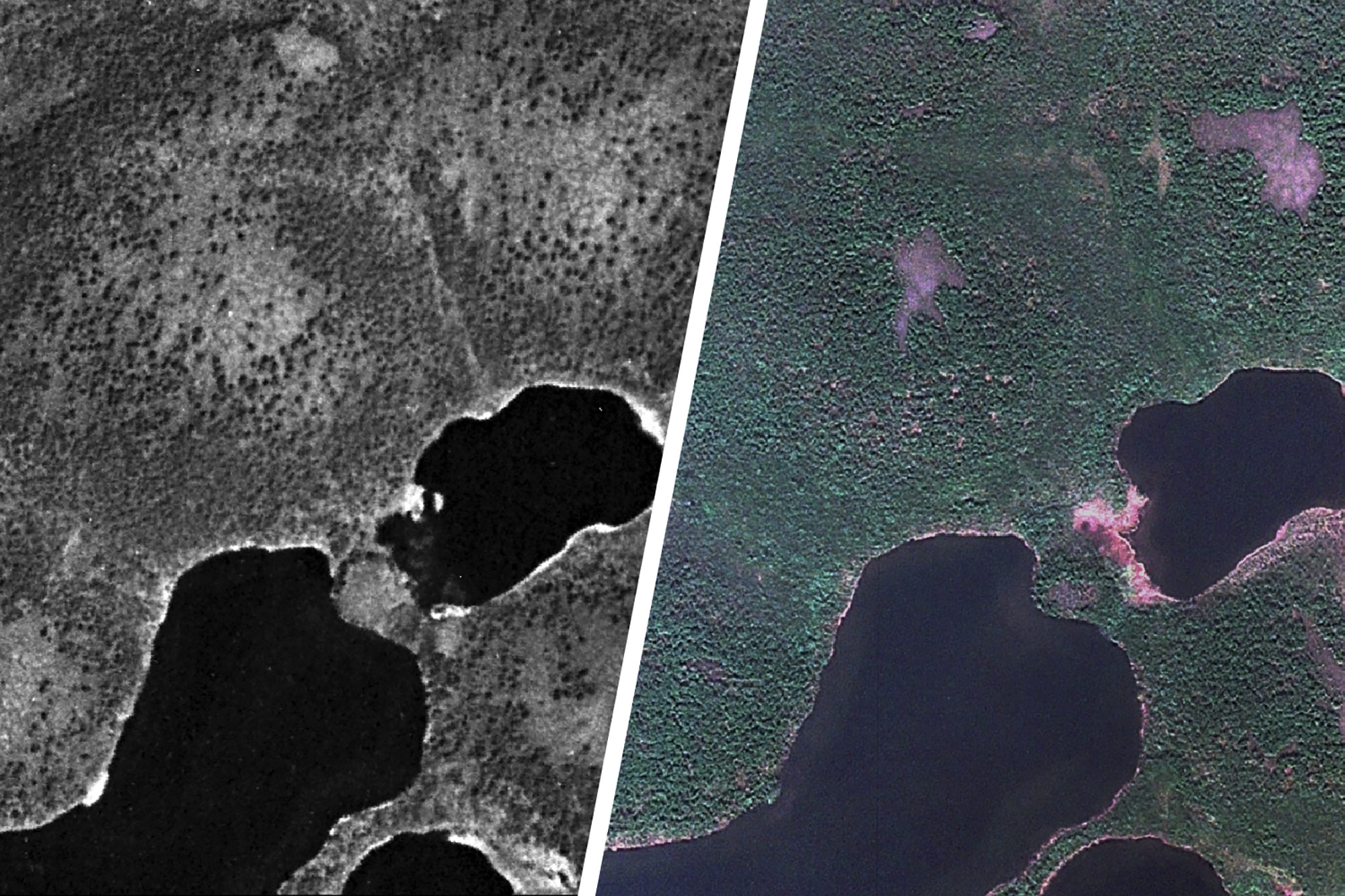

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the U.S. declassified tens of thousands of images obtained from its two major spy satellite programs, Corona and Gambit. Many of these highly detailed photographs, taken from 1960 through 1984, are of the massive and relatively little-studied western Siberian tundra. The government was looking for military installations and nuclear arsenals, but it found mostly undeveloped, wild terrain.

It occurred to University of Virginia environmental scientists that the imagery is a storehouse of information for better understanding how vegetation in tundra regions may be altering as a result of climate change and other factors.

Caption: Environmental scientist Howie Epstein studies changes to Arctic tundra related to climate change. (Photo by Dan Addison, University Communications)

“These spy images are a gold mine as a reference point,” environmental sciences professor Howie Epstein said.

He oversaw a study comparing old spy photographs from 1960 into the 1980s with environmental images of the same terrain made in more recent years from commercial satellite sensors. “We are able to look at the exact same locations, in close detail, across several decades,” he said.

Epstein and his graduate student, Gerald Frost, who conducted the study as part of his Ph.D. dissertation, tracked 11 sites in Siberia through half a century of imagery, and were able to distinguish the expansion of tall shrubs such as alder, willow, birch and dwarf pine. They found that tall shrubs and trees had expanded their range in some areas by up to 26 percent since the 1960s, though the overall expansion was less dramatic.

“We know from Earth-observing satellite data that the Arctic generally has been greening for 35 years or so,” Epstein said. “But the Siberian tundra had not been as closely observed until relatively recently. We now know that a lot of greening has been going on there, too, with tall shrubs and woody vegetation. The vegetation has been getting both taller and expanding in space and range.”

This possibly and likely could be attributable to climate change, he said – specifically, a generalized warming of tundra climate – but it also is more complex than that.

As the shrubbery increases its distribution, it creates its own warming effect by absorbing heat, rather than reflecting heat as snow does, leading to additional warming and perpetuating the effect. This also changes the distribution of landscape snow, the balance of plant and animal species in the warmed areas, and the normal ratios of plants to herbivores. As the species distribution changes, it also alters the amount of carbon cycled among the air, vegetation and soil, which in turn affects climate.

Epstein and Frost – now a scientist with ABR Inc., an environmental research and services firm in Fairbanks, Alaska – have also conducted ground studies in some of the same areas they’ve observed via satellite imagery. Some of their fieldwork is in a remote area near Kharp in the northwest central part of Russia. For several summers, they were able to secure rides on an old treaded armored vehicle across the tundra to exact sites they’d examined in photographs, allowing them to “ground truth,” in effect, what they’d seen in the satellite imagery.

Researcher Gerald Frost stands before an old Russian armored vehicle he and Epstein used to study remote areas of Arctic tundra.

“We found that shrubs were using circular bare spots on the ground, naturally caused by freezing and thawing, to expand across the landscape,” Epstein said. “By using those bare spots for expansion, the shrubs were taking advantage of the lack of competition from other species. The shrubs grow quickly and have tough roots.”

But while vegetation clearly has expanded in the tundra during the past few decades, as documented by the old spy imagery and the new commercial data, Epstein said the “greening” in some places might now be reversing.

“We’re starting to find a browning of the tundra in the last few years,” he said. “The progression of growth may be reversing. We’re not sure yet why, but it’s clear that vegetation dynamics are more complex across tundra than previously thought. We still have a lot of work to do to understand Arctic changes and how this affects and is affected by changes to the global climate.”

Media Contact

Article Information

April 6, 2017

/content/cold-war-era-spy-satellite-images-reveal-possible-effects-climate-change