Laughter and worried sharp intakes of breath occasionally drowned out the subtle whirr of servo motors as teams of first-year University of Virginia engineering students enrolled in an introductory course remotely choreographed the movements of 2-foot-tall humanoid robots.

The students directed the French-made NAO (pronounced “now”) robots – which feature stocky legs, narrow hips, high shoulders and hands with two fingers and a thumb – to dance, sometimes to music. One machine shifted its weight onto one leg and slowly kicked the other one out to the side, and then switched legs. After it completed the maneuver, it moved its arms back and forth and around. Then the NAO rocked a little bit and toppled over backward, with a student catching it from behind before it hit the soft mat on which it had been dancing.

Aside from dancing, students programmed the machines to ring hand bells and shake maracas, and one group even tried to program its robot to play a toy piano. On their commands, the students’ robot stood, stretched out its arms and then gently brought its fists down on the keyboard, just like a human infant might.

Keith Williams, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and director of UVA’s introductory engineering program, chose to start these first-year students with completed robots, instead of having them build them from scratch, because he said it is important for the students to see what they can eventually achieve and motivate them to reach for the state of the art.

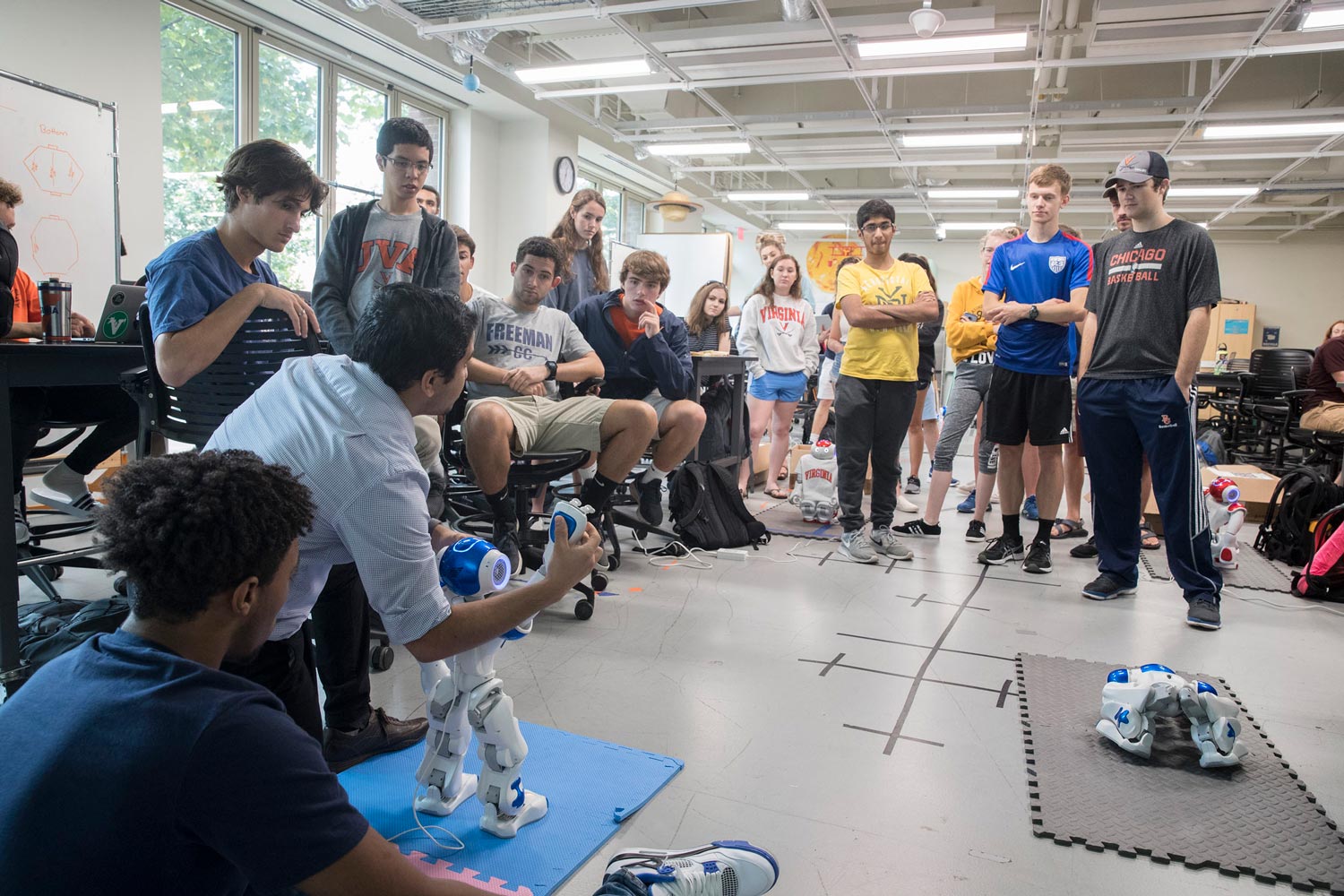

Engineering professor Keith Williams, left, works with students on programming their robot to follow commands. (Photos by Dan Addison, University Communications)

The students worked with their humanoid machines for several classes. Graduate student Sid Shenoy opened the first session with a video presentation on the NAO robots, followed by a brief overview video of a Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency robotics competition in which machines were programmed to complete a series of tasks, such as opening a door, walking over an uneven surface, turning a valve, and driving and exiting a vehicle.

Williams then passed out boxes containing the robots; the students removed the machines, lifting the $8,000 robots gently under the armpits and cradling their heads as if they were newborn infants.

“It’s a lot more difficult than it looks,” Williams said as the students huddled in groups on the floor, swapping ideas and suggestions and punching commands into their laptops. “Human interactions are a lot more robust than human/robot interactions. The students have to think through every subtle piece of the human-robot interaction.”

“This teaches students how hard it is to get a robot to do anything,” said Joanne Dugan, another professor of electrical and computer engineering who uses the robots with upperclass students. She first saw the NAO robots at an academic conference dancing to the Korean pop hit, “Gangnam Style.”

Working with robots teaches the new students teamwork; they take turns working on a laptop, guarding the machine from toppling or holding up objects for the machine to “recognize.”

“We all take different roles on our team,” said Jack Smith T, from Birmingham, Alabama, whose team was programming its robot to play a toy piano. Smith T typed commands into the computer while a teammate observed how the machine reacted to each new order and another teammate hovered over the NAO to catch it if it should fall.

The machines have the ability to react to any objects that pass before their “eye” sensors. Students waved different things in front of them, and the robot’s eyes changed color when it “recognized” something. One student held a red plastic orb in front of her machine and the NAO said, “That’s a tomato” over and over, as long as the student held the object in its line of sight. (Another team member suggested they program the robot to say that in French, to break the monotony of the repetition.) Teams set up whiteboard backdrops in the robots’ field of view, so the machines would not be distracted by background movement.

One sports-minded group sought to instruct its machine to putt an oversized plastic golf ball using a hollow plastic golf club clutched in one mechanical hand. The team wrestled with the programming difficulties of softly twitching the robot’s arm to tap the ball into an upright hole.

Teaching the students to program humanoid machines gives them an understanding of the nuances required for even short, simple movements; because the machines have arms, legs and a head, it is easy for the students to anthropomorphize them.

“That aspect humanizes the technology, and makes it more approachable,” Williams said.

“It is a way to have a discussion about the societal implications of robot-human relationships,” Dugan said. “‘Are these things going to take away my job?’ They walk through every step of the human/robot relationship, and because the robots are human-shaped, we expect more sophisticated behavior from them.”

Williams said he sees the machines and their capabilities as more of an asset to humanity than a threat.

“I think they are going to bring a growth of productivity,” he said. “I see them magnifying human capabilities, rather than replacing them.” He cited technologies such as FarmBot, which is designed to handle agricultural labor tasks.

The students marveled at their robots and their ability to move, to step right or left at a set of commands and wave their arms in a rhythmic manner, but at the same time, the students extended their hands around the fragile equipment, as if the machines were children, vigilant to catch them if they wobble and threaten to tumble.

Graduate student Sid Shenoy demonstrates to first-year engineering students how to program the short NAO robots.

Although they are first-year engineering students, for some this is not the first introduction to robotics. Anne Forrest Butler encountered robots in her Charlotte, North Carolina, high school.

“We built a robot in six weeks,” she said. “I really loved it and it is fun to do it again. I would like a career using robots to build rockets.”

Butler’s team members satisfied themselves with getting their machines to recognize objects and track them as they move and to program the machine to shake a hand bell.

“We are learning teamwork and patience,” Butler said.

One machine in the center of the room toppled over on its padded mat and the class fell silent as students craned their necks to see if the robot had been damaged. It appeared uninjured.

Nicole Beachy of Midlothian said her team thought it would be fun to have their robot dance to music from the 1990s and they programmed it to move to “The Macarena.” It went through the routine twice and the second time, it fell over at the end.

“This is a cool experience,” Beachy said. “I haven’t been exposed to this before. These machines have a lot of power and there is more we can do with them.”

Media Contact

Article Information

October 10, 2018

/content/dancing-robots