A couple of weeks into his first semester at the University of Virginia, Marques Hagans awoke on a Tuesday knowing he had a physics quiz later that morning. He was a little anxious about the test, but upon reaching his classroom Hagans learned, to his surprise, that the class had been canceled.

No explanation was given, but when Hagans, a first-year quarterback on the UVA football team, walked into Newcomb Hall, he came upon a scene he still remembers two decades later.

“I saw everybody crying,” Hagans, now the Cavaliers’ wide receivers coach, said this week, “and then I saw the TV and I saw the towers.”

It was Sept. 11, 2001, a day stamped in United States history. At 8:46 a.m., a hijacked commercial airplane loaded with 20,000 gallons of jet fuel crashed into the north tower of the World Trade Center in New York City. Seventeen minutes later, another hijacked jet crashed into the south tower.

More devastation followed. At 9:45 a.m., a third hijacked plane struck the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., and at 10:10 a.m., a fourth jet, after an on-board battle between passengers and hijackers, crashed into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

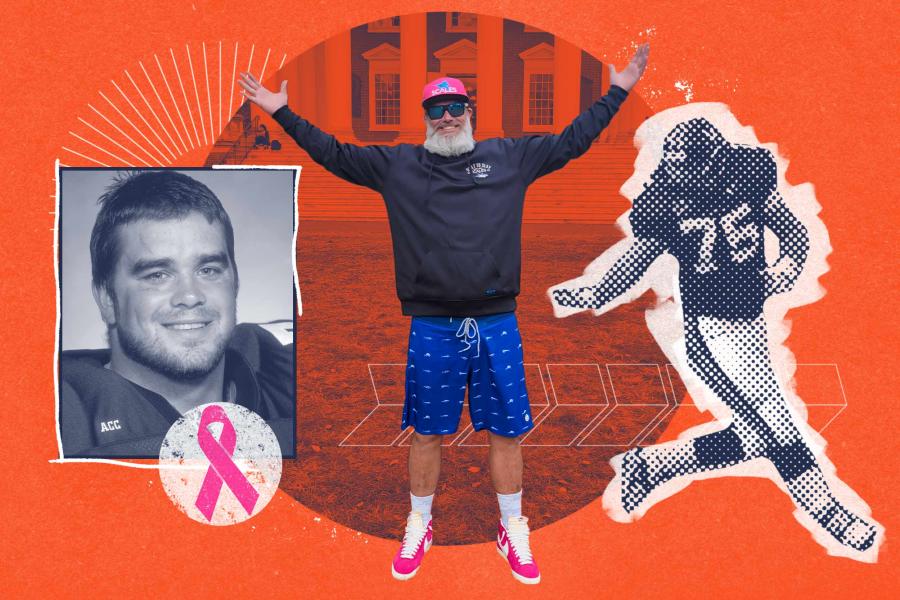

Marques Hagans was a first-year quarterback on the UVA football team in 2001.

In all, nearly 3,000 people were killed in the terrorist attacks.

“It’s a day that sticks in memory, for lots of reasons,” Al Groh said this week.

The 2001 season was Groh’s first as head football coach at UVA, his alma mater. He was in his McCue Center office, Groh recalled, when a colleague “came in and said, ‘You gotta turn on the television and see what’s happening.’ This was fairly early in the morning, probably quickly after all this started showing up on TV. So as I saw where it was and what was happening, I had a sense of what was going on.”

The Cavaliers, whose record was 1-1, were scheduled to host Penn State at Scott Stadium two days later, and “certainly any time ESPN is broadcasting a Thursday night game, particularly if it’s on your campus, the magnitude of the game takes on added importance,” Craig Littlepage said this week.

Littlepage, who had been promoted to athletics director at UVA on Aug. 21, 2001, had his radio on as he drove to Scott Stadium for a game-operations meeting early on Sept. 11.

“It was five minutes before 9,” Littlepage recalled, “and the local news was pre-empted by the network news out of New York saying that there was a report of a plane that had crashed into the World Trade Center, and the information was still in its infancy at the time. My first thought was that there was some sort of air traffic control problem or some sort of mechanical issue with a plane.

“I had a vision of a small private plane as opposed to a commercial airliner, but I proceeded over to the stadium, and as I walked into the room I walked by our University police chief, Paul Norris, and he whispered in my ear that a plane had been flown into the World Trade Center and that it wasn’t an accident with a small private aircraft, it was a major commercial airliner, and all of a sudden it just kind of took the air out of us as we were trying to process this.

“As the meeting got started, that was the first thing that was discussed, that we didn’t know what was going on, but there was some sort of major incident taking place in New York City. We proceeded, as I recall, with the meeting because we still didn’t have enough information to know just how dire the situation was. But by the time we got out of that meeting, we knew that it was something that had far more implications than anything else that we had ever dealt with administratively.”

Former athletic director Craig Littlepage in 2001.

Back in the McCue Center, Gerry Capone, who was then UVA’s associate athletic director for football administration, recalls coming out of a meeting on the third floor and seeing the TV on in the office of executive assistant Becky Davis.

“I remember it like it was yesterday,” Capone said this week. “The first plane had just flown into the building, and we all came out of the [meeting] room and into her office. Everybody was in shock.”

That was true throughout the athletics department, Capone said. “People were glued to TVs.”

For some staff members, the chaos in lower Manhattan was especially agonizing. Defensive coordinator Al Golden’s father worked for Cantor Fitzgerald, a financial services company in one of the towers, and “although he was not at that time going to work every day, he was going in on different days each week and had an office in there,” Groh said. “And so clearly Al was very distressed about his father’s potential circumstances, and it took quite a while into the course of the day for him to be able to have communication and get the word that his dad was OK.”

Groh also remembers trying to determine the whereabouts of Tim Coughlin, a former UVA baseball player whose family was close to the Grohs. (Coughlin’s father, Tom, is a former NFL head coach.)

“For a while there was concern amongst their family as to where Tim was,” Groh said, “because he would on occasion go into the twin towers, for whatever job he had at that time. Fortunately, he wasn’t in there either, but besides just concern for the city of New York, for the country, for the people and the families that were physically involved in all of that, there was some personal concern within our office for Tim and for Al’s dad. So those two things tied up a lot of our thoughts and a lot of phone calls with a variety of people.”

With many phone lines down in New York City, communication was difficult.

“You might think, why couldn’t Al just call his dad or call his mom and find out if his dad went to work that day?” Groh said. “It took many hours for that simple phone call to actually be able to go through and for Al to get the news.”

Rich Riccardi, who had played football and lacrosse at UVA, was in a building near the towers when the attacks began, Capone learned two days later.

“He was fine,” Capone said, “but when the first plane hit, they all evacuated, and as he was coming out of the building he could see the plane coming over the top of him to go into the second building. And he said he just put his head down and took off. He said people were jumping out of the first building, and he put his head down and started running north, which was toward the George Washington Bridge.”